AUGUST

Revenue

Guide

for Washington Cities and Towns

I

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

2019 re-write created in partnership with

The Center for Government Innovation, a service of the Washington State Auditor’s Oce

REVENUE GUIDE FOR WASHINGTON CITIES AND TOWNS

Copyright © 2024 by the Municipal Research and Services Center of Washington (MRSC). All rights reserved.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or

distributed in any form or by any means or stored in a database or retrieval system without the prior written

permission of the publisher; however, governmental entities in the state of Washington are granted permission

to reproduce and distribute this publication for ocial use.

DISCLAIMER

The content of this publication is for informational purposes only and does not represent criteria for legal or

audit purposes. It is intended to provide city sta and ocials with an overview of their available revenue

options, restrictions on the use of such revenues, and key questions to consider. It is not intended to replace

existing prescriptive guidance in the BARS Manual, issued by the State Auditor’s Oce. You should contact

your own legal counsel if you have a question regarding your legal rights or any other legal issue.

MRSC MISSION

Trusted guidance and services supporting local government success.

MRSC

OFFICE: 225 Tacoma Ave S., Tacoma, WA 98405

MAILING: 1712 6th Ave, Suite 100, PMB 1330, Tacoma, WA 98405

(206) 625-1300 | (800) 933-6772

www.MRSC.org

II

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

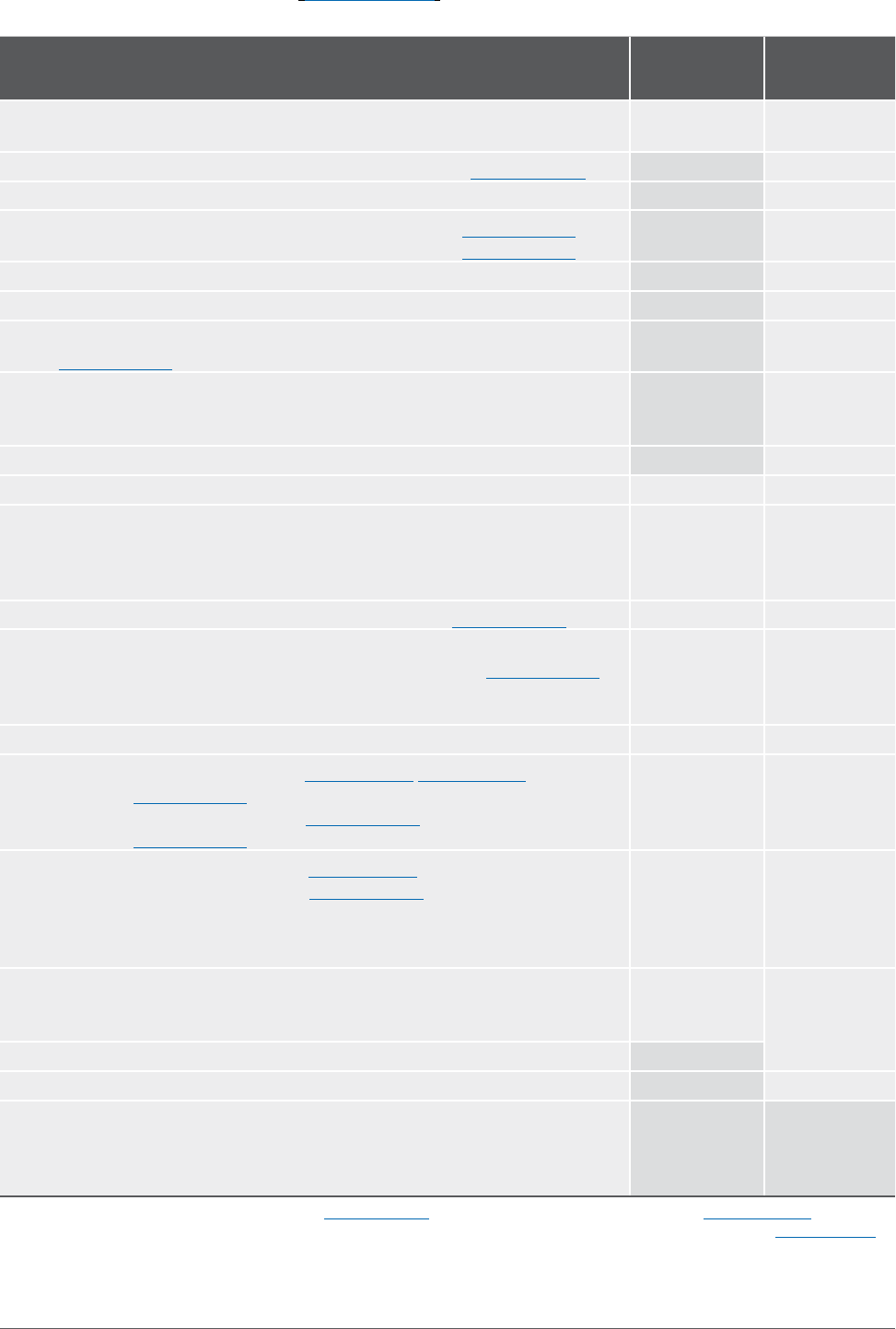

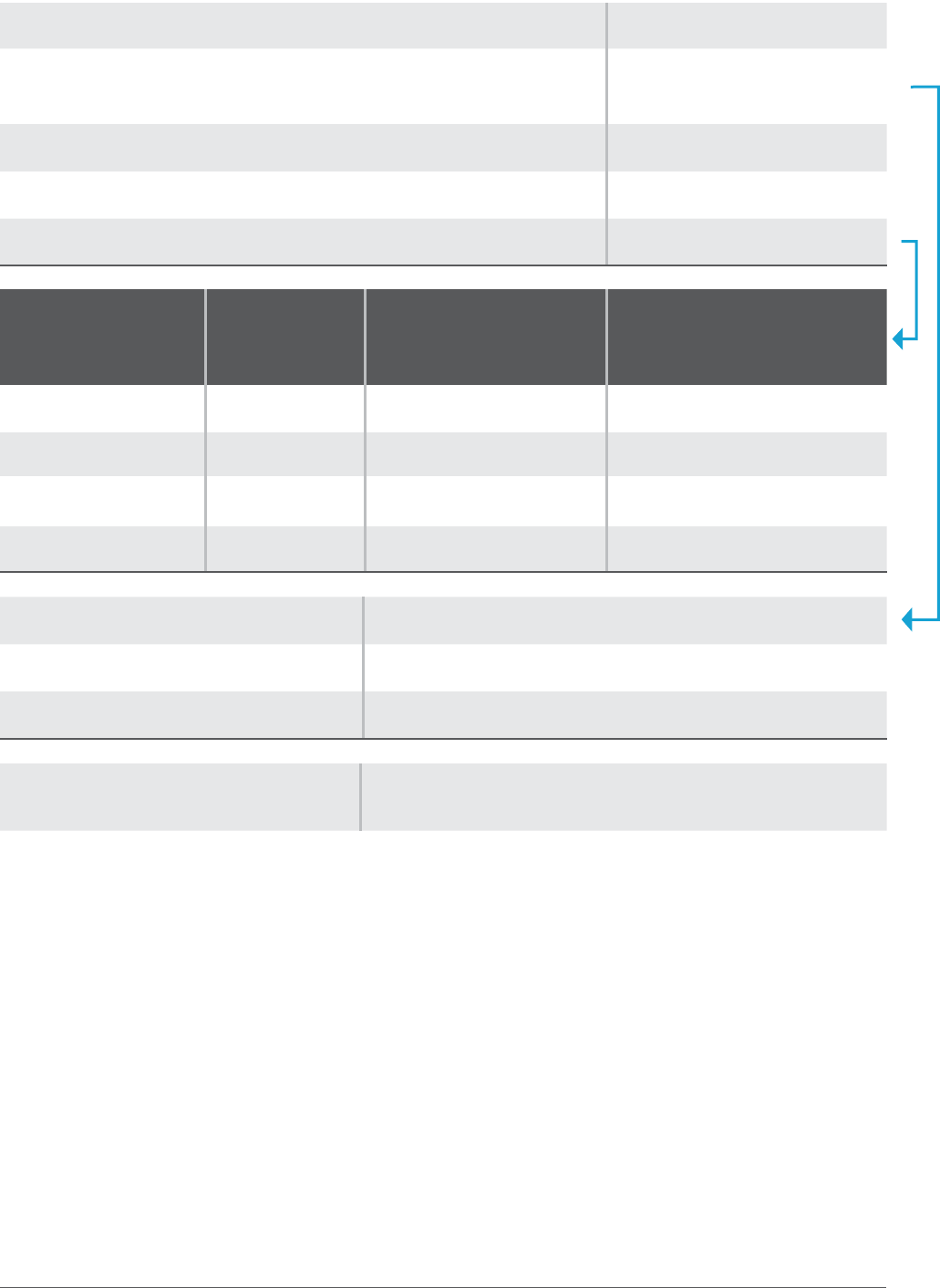

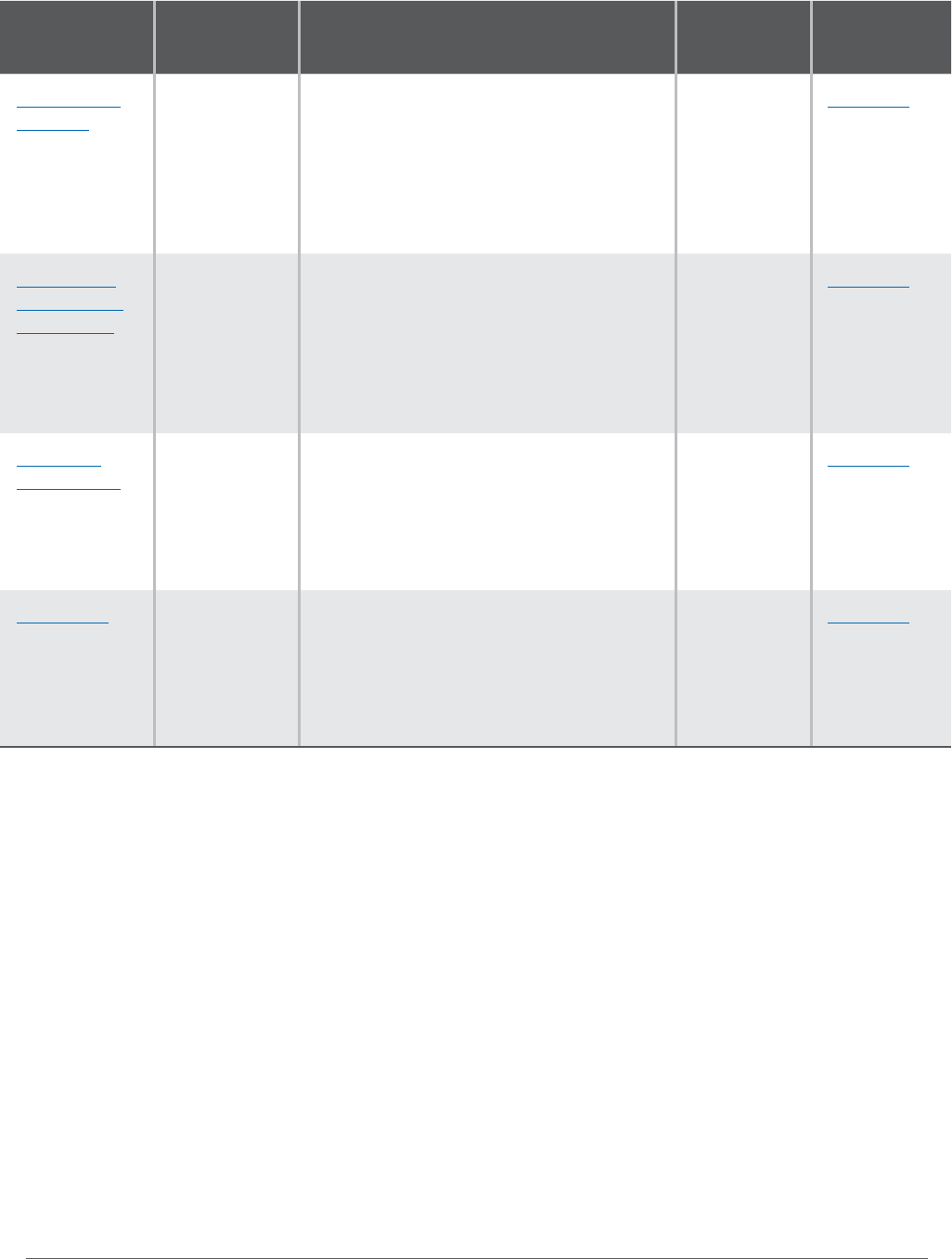

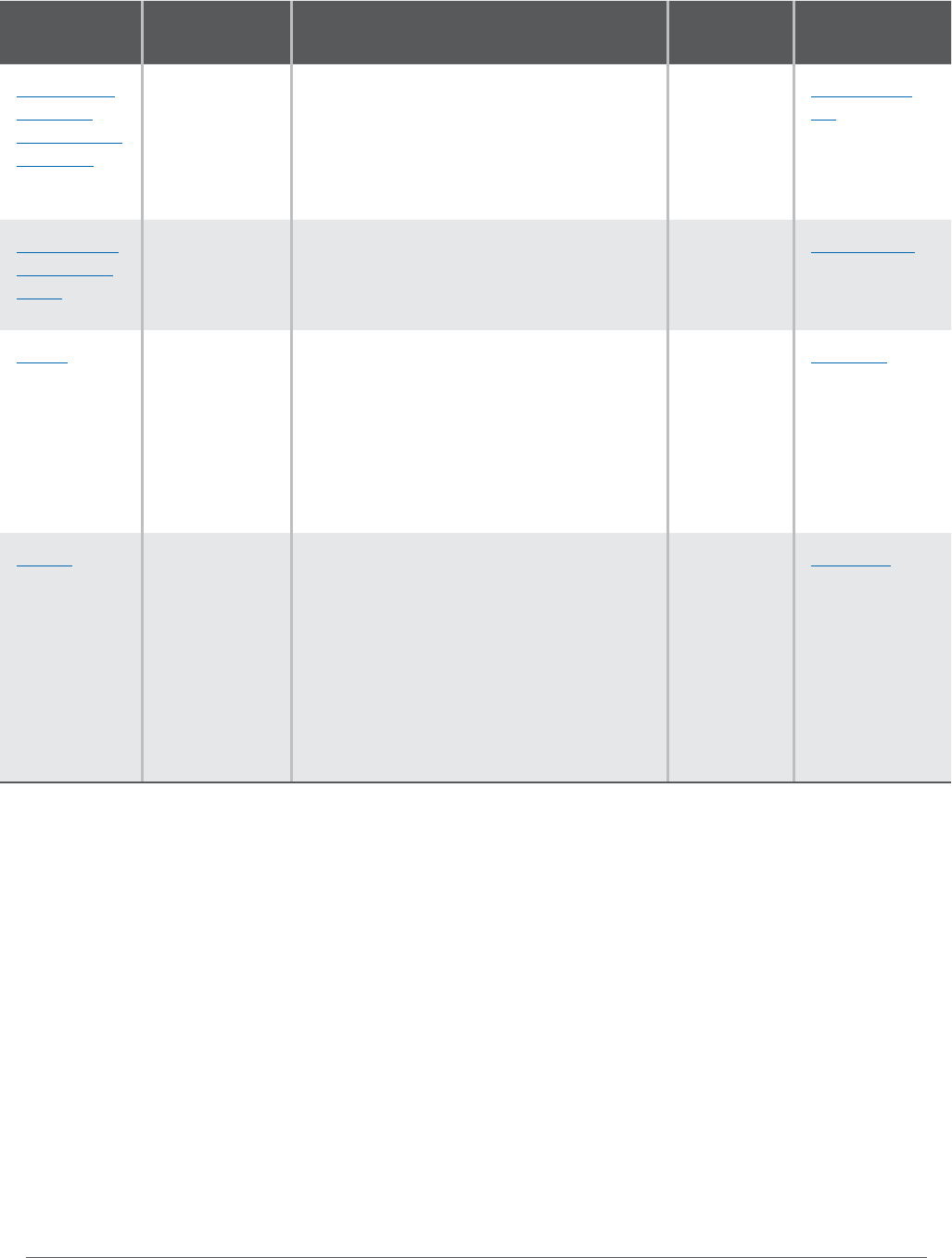

Revision History

MRSC does our best to update this publication every year to reflect any new legislation or other relevant

information impacting city and town revenues. Below is a summary of significant recent changes over the last three

legislative sessions. If you are aware of any other sections that you think need to be updated or clarified, please

contact [email protected]. To make sure you have the most recent version, please go to mrsc.org/publications.

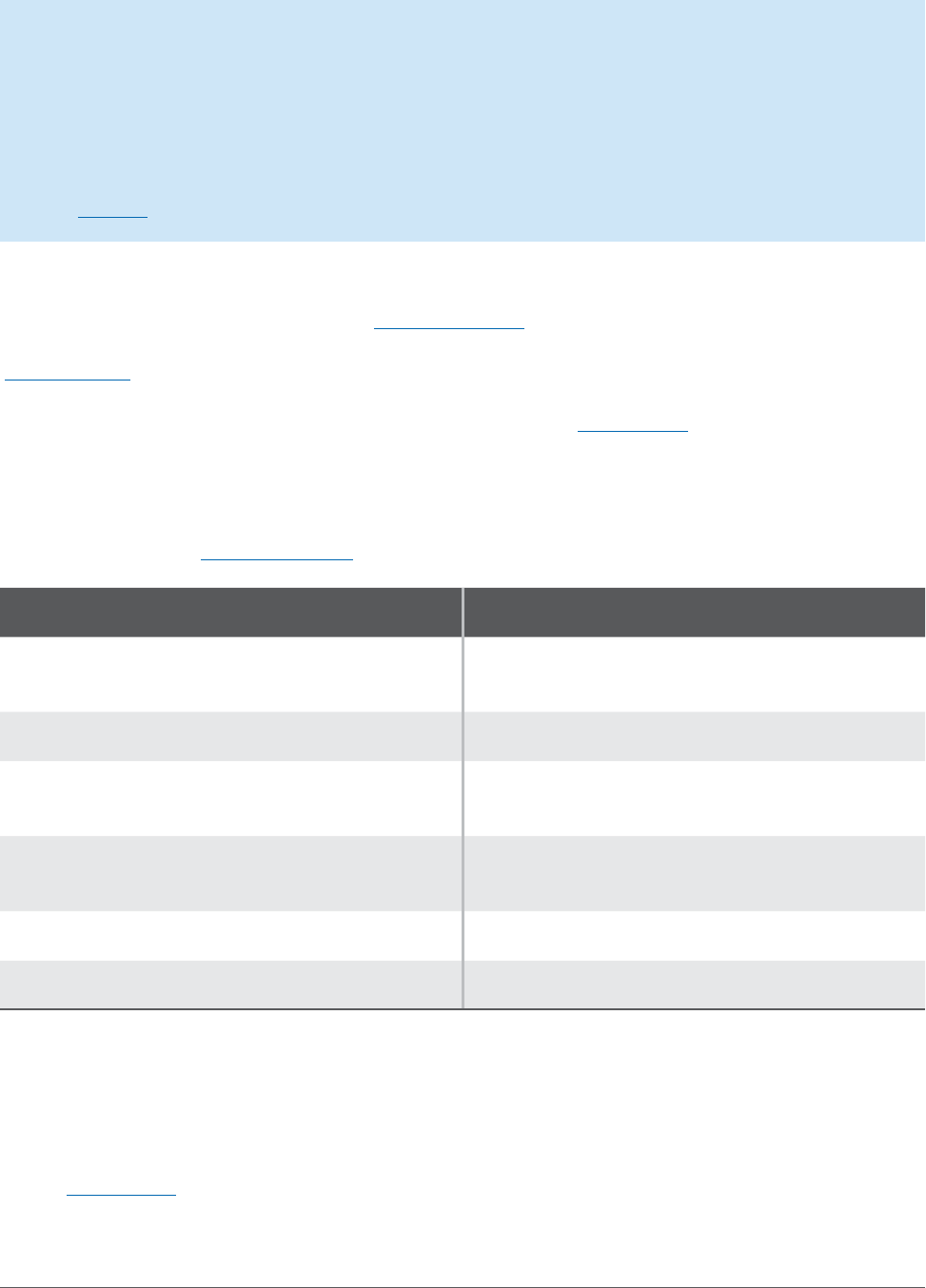

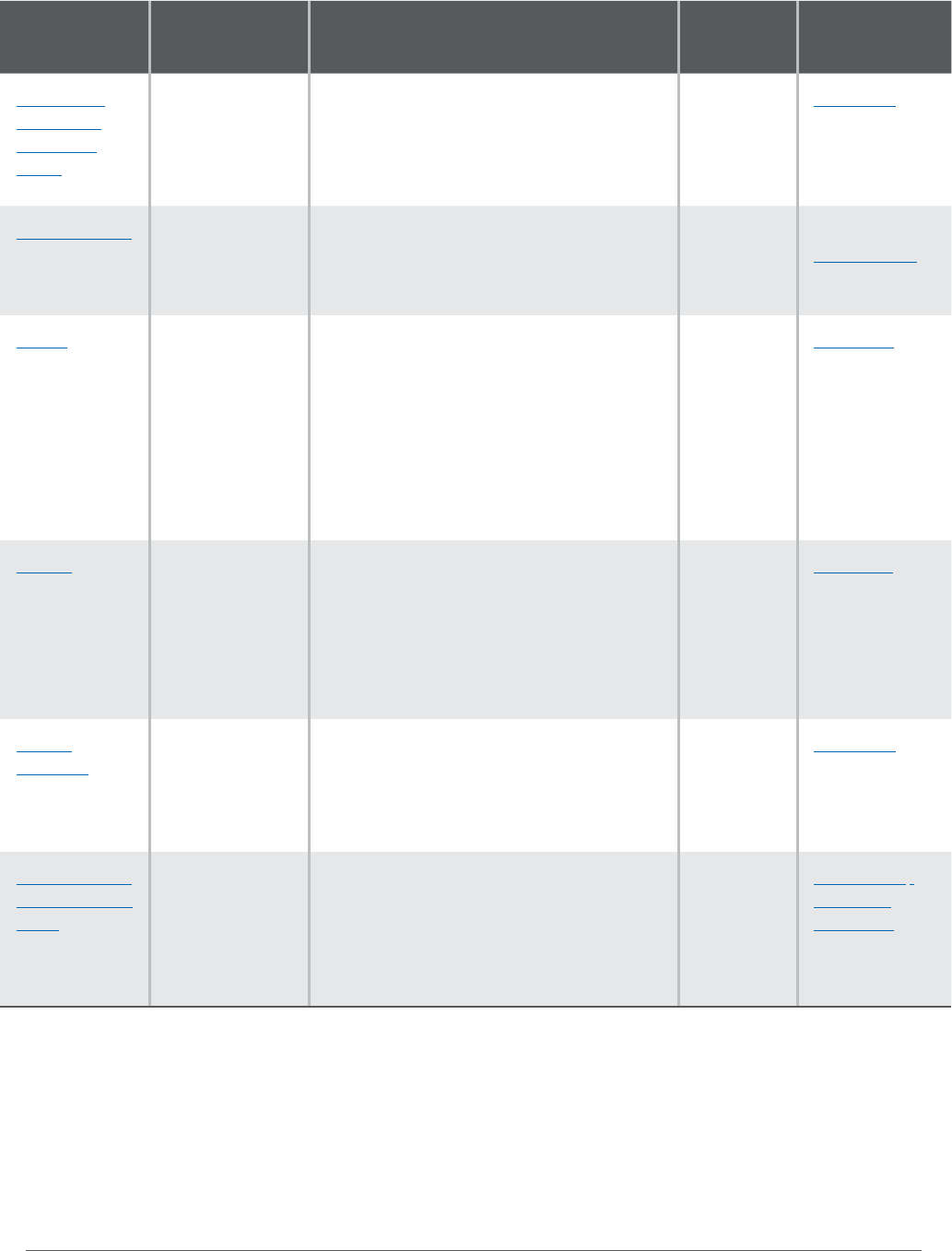

DATE SUMMARY

August 2024 A Brief History of Local Taxing Power in Washington

• Cities and towns are prohibited from taxing any individual person on any form of

personal income (Initiative ).

Retail Sales and Use Taxes

• Clarified that there are certain exceptions to the destination-based sales tax,

including motor vehicle and boat sales which are taxed based on the location of

the dealership/seller.

• “Basic” Sales Tax/First Half-Cent. Cities and towns may enter into interlocal

agreements to share a portion of this revenue (HB ).

• “Optional” Sales Tax/Second Half-Cent. Cities and towns may enter into

interlocal agreements to share a portion of this revenue (HB ). All cities,

towns, and counties now impose the full .% “optional” sales tax.

• Aordable Housing Sales Tax Credit (HB ). Revenues may now be spent

on housing and services for people at or below % of local median income if

the housing is intended for owner occupancy (SB ).

Property Taxes

• Levy Lid Lifts. Supplanting restrictions for multi-year levy lid lifts have been

removed from jurisdictions in King County (HB ).

Real Estate Excise Taxes (REET)

• REET in Lieu of “Second Half” Sales Tax. Clarified that revenues are restricted in

same manner as REET 1, but that no jurisdictions are eligible any more as all cities,

towns, and counties have now imposed the optional “second half” sales tax.

“State Shared” Revenues

• Cannabis (Marijuana) Excise Tax. Updated statutory reference; clarified that first-

class cities and code cities might be able to impose local cannabis excise taxes.

Other Revenue Sources

• Tourism Promotion Area Fees. Fees do not apply to any lodging business,

lodging unit, or lodging guest designated as exempt by the legislative body

(HB 2137).

III

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

DATE SUMMARY

November 2023 Retail Sales and Use Taxes

• Aordable Housing Sales Tax Credit (HB ). New legislation allows all

jurisdictions to use revenues for rental assistance and limited administrative

costs, regardless of population (SB ).

• Annexation Services Sales Tax. New legislation temporarily reinstates and

expands this sales tax credit (HB ).

• Criminal Justice Sales Tax. Removed reference to “fiscal flexibility” bill,

which expires December , .

• Cultural Access Program (CAP) Sales Tax. New legislation allows jurisdictions to

impose sales tax councilmanically; through December , this sales tax

may only be imposed by counties (HB ).

• Public Safety Sales Tax. Removed reference to “fiscal flexibility” bill, which

expires December , .

Lodging Tax (Hotel/Motel Tax)

• Reporting Requirements. Removed reference to exact date of JLARC reporting

deadline. Deadline is established internally by JLARC and subject to change.

Real Estate Excise Taxes

• REET – The “First Quarter Percent.” Removed reference to “fiscal

flexibility” bill, which expires December , .

• REET – The “Second Quarter Percent.” Removed reference to “fiscal

flexibility” bill, which expires December , .

“State Shared” Revenues

• Criminal Justice Distributions. Removed reference to “fiscal flexibility” bill,

which expires December , .

• Streamlined Sales Tax (SST) Mitigation Payments. Deleted section; payments

expired June 30, 2021.

December 2022 Retail Sales and Use Taxes:

• Transportation Benefit District Sales Tax. Maximum authority increased to 0.3%;

up to 0.1% can potentially be imposed councilmanically; may be renewed in 10-

year increments indefinitely (ESSB 5974 § 406-407).

• Timing of Sales Tax Rate Changes. Updated Department of Revenue contact

information.

Other Excise Taxes:

• Border Area Fuel Tax. Maximum voter-approved tax rate increased to cents

per gallon plus inflation adjustment. (ESSB § ).

“State Shared” Revenues:

• Cannabis (Marijuana) Excise Tax. Distribution formula changed (ESSB ).

Updated terminology from “marijuana” to “cannabis” for consistency with new

state law (SHB ).

IV

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

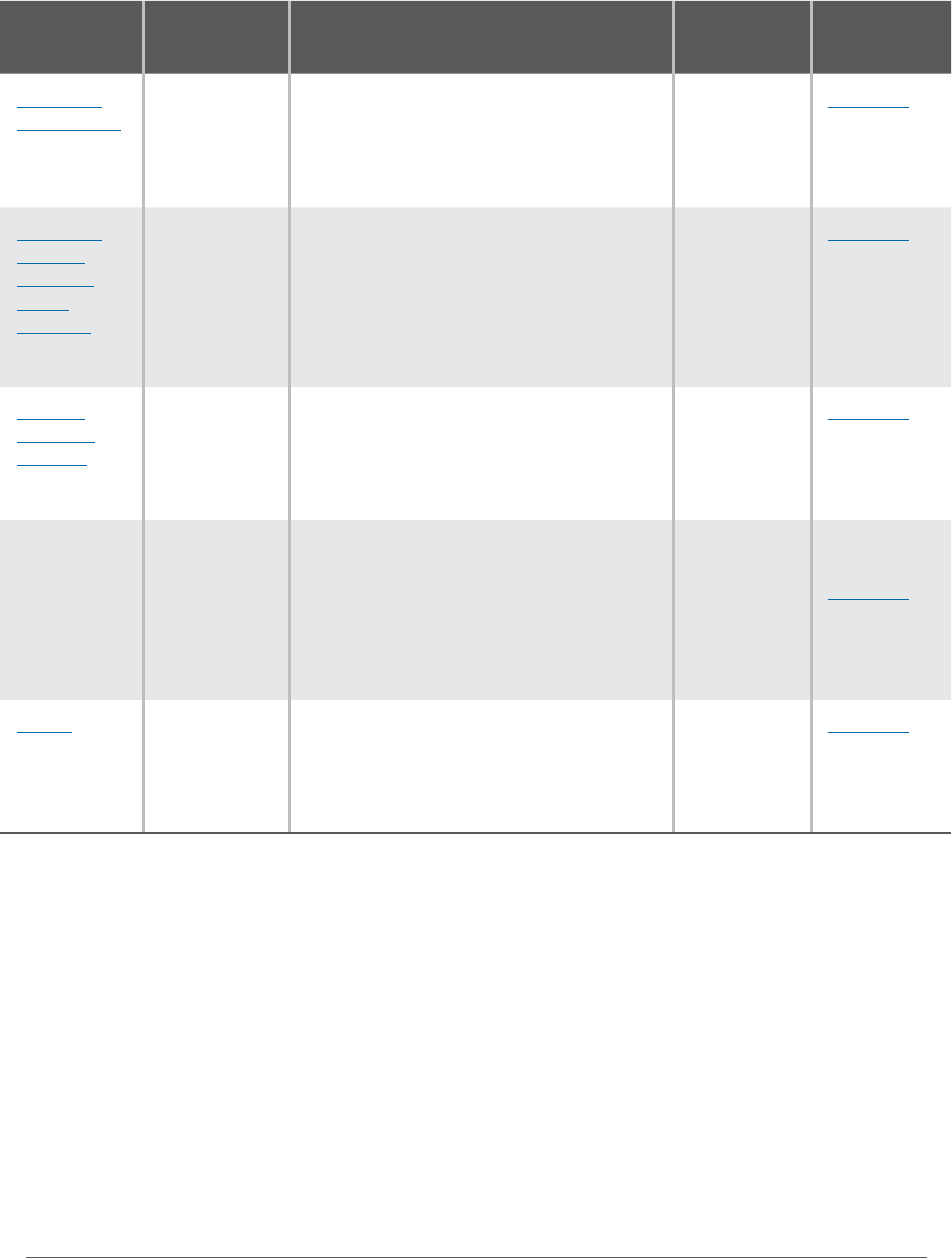

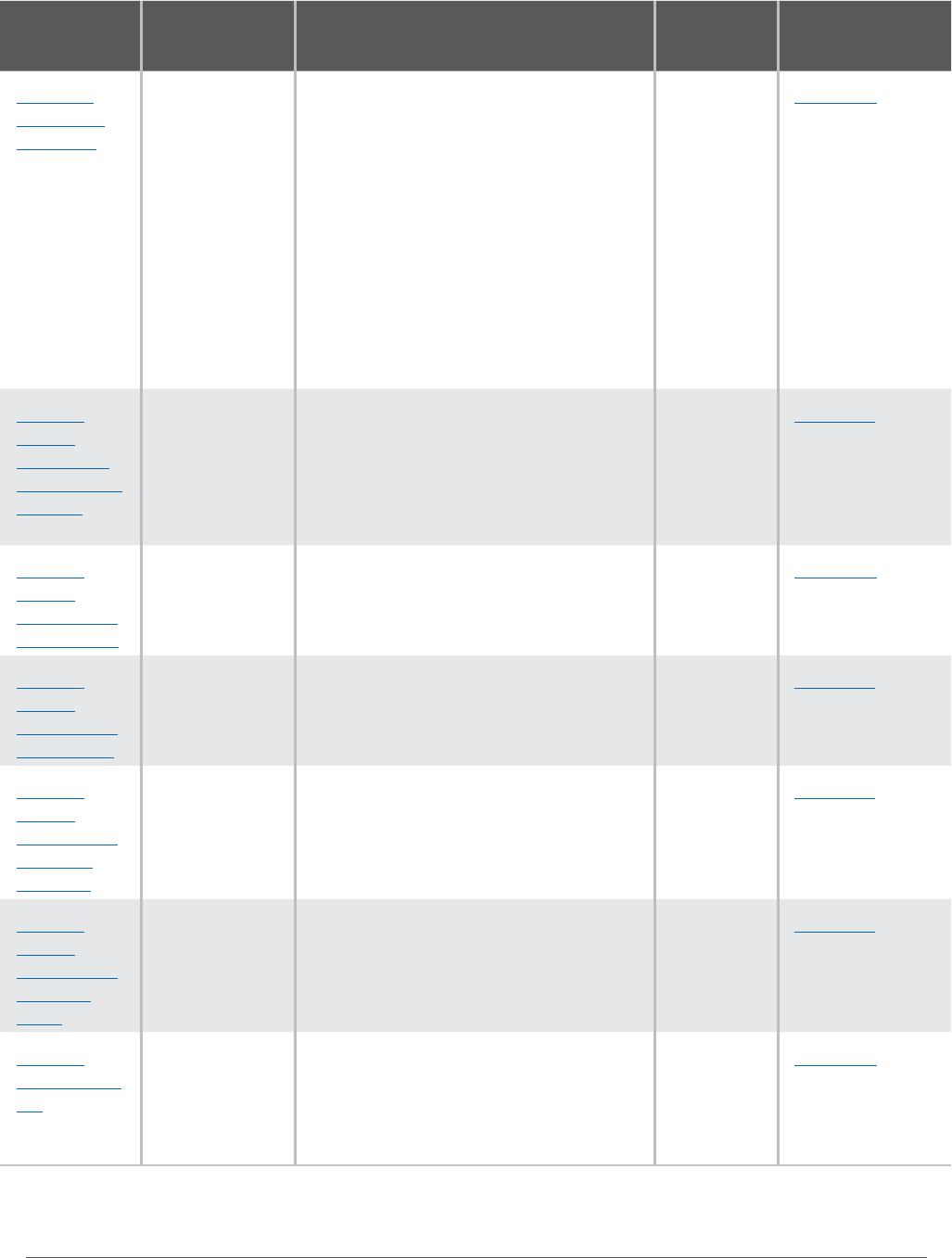

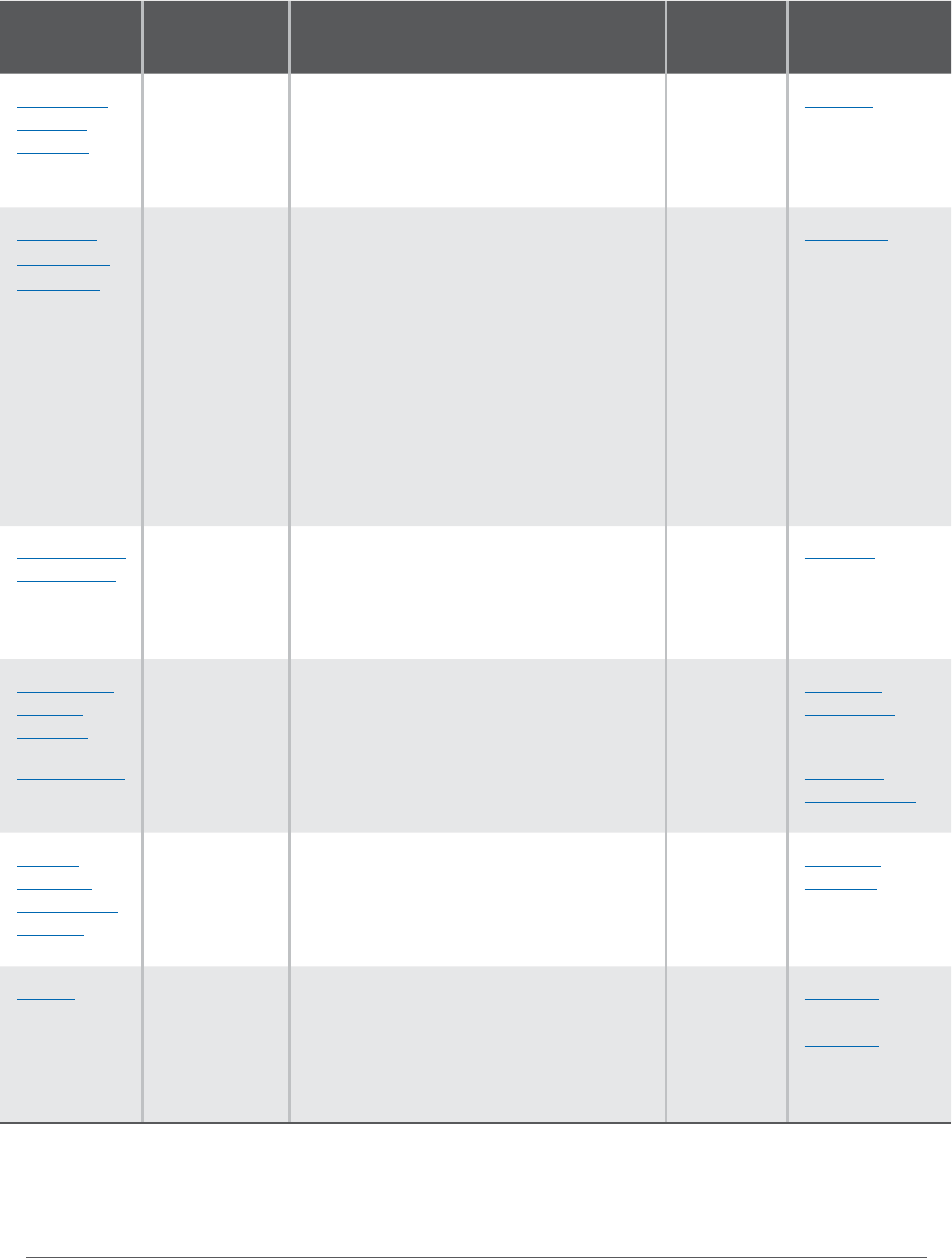

Contents

Introduction

How to Use this Document

A Brief History of Local Taxing Power in Washington

Key Considerations for Evaluating Revenue Sources

Key Considerations for Voted Revenue Sources

Key Deadlines for Voted Property Taxes and Sales Taxes

Property Taxes

What is a Budget-Based Property Tax?

Maximum Aggregate Levy Rates

Regular Levy (General Fund)

Aordable Housing Levy

Cultural Access Program (CAP) Levy

Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Levy

Excess Levies (Operations & Maintenance)

G.O. Bond Excess Levies (Capital Purposes)

Refunds and Refund Levies

The 1% Annual Levy Lid Limit (“101% Limit”)

Banked Capacity

Levy Lid Lifts

Validation/Voter Turnout Requirements

Annual Levy Certification Process

Receipt of Property Tax Revenues

Retail Sales and Use Taxes

What Items Are Taxed?

Sales Tax Exemptions

What is a Use Tax?

“Basic” Sales Tax/First Half-Cent

V

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

“Optional” Sales Tax/Second Half-Cent

Aordable Housing Sales Tax Credit (HB 1406)

Annexation Services Sales Tax

Criminal Justice Sales Tax

Cultural Access Program (CAP) Sales Tax

Housing & Related Services Sales Tax

Mental Health & Chemical Dependency Sales Tax

Public Safety Sales Tax

Transit Sales Tax

Transportation Benefit District Sales Tax

Timing of Sales Tax Receipts

Timing of Sales Tax Rate Changes

Maximum Tax Rate for Sales of Lodging

Business and Utility Taxes & Fees

Business and Occupation (B&O) Taxes

Utility Taxes

Brokered Natural Gas Use Tax

General Business License Fees

Regulatory Business License Fees

Revenue-Generating Business License Fees (“Head Taxes”)

Lodging Tax (Hotel/Motel Tax)

“Basic” or “State-Shared” Lodging Tax

“Additional” or “Special” Lodging Tax

Lodging Tax Advisory Committees and Use of Funds

Reporting Requirements

Real Estate Excise Taxes (REET)

REET 1 – the “First Quarter Percent”

REET 2 – the “Second Quarter Percent”

REET In Lieu of “Second Half” Sales Tax

Other REET Options

VI

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Other Excise Taxes

Admission Tax

Border Area Fuel Tax

Commercial Parking Tax

Gambling Tax

Leasehold Excise Tax

Local Household Tax

Local Option Gas Tax

Timber Excise Tax

“State Shared” Revenues

Cannabis (Marijuana) Excise Tax

Capron Refunds

City-County Assistance (ESSB 6050) Distributions

Criminal Justice Distributions

Fire Insurance Premium Tax

Liquor Distributions

Motor Vehicle Fuel Tax (MVFT)

Multimodal Funds and Increased MVFT

Public Utility District (PUD) Privilege Tax

Other Revenue Sources

Franchise Fees

Impact Fees – Growth Management Act (GMA)

Impact Fees – Local Transportation Act (LTA)

Investments (Interest Earnings)

Parking Meters

Surplus Transfers from Utilities and LIDs

Tourism Promotion Area Fees

Trac and Parking Fines

Transportation Benefit District Vehicle License Fees

Utility Rates and Charges

Other Fees and Charges

VII

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Special Taxing Districts

Fire Protection District

Library District

Metropolitan Park District

Public Facilities District

Regional Fire Authority

Transportation Benefit District

Appendices: Major Revenue Sources by Program Area

Appendix A – Unrestricted Revenues

Appendix B – Aordable Housing

Appendix C – Arts, Science, and Cultural Programs

Appendix D – Capital Projects and Facilities

Appendix D – Capital Projects and Facilities – continued

Appendix E – Fire and Emergency Medical Services Services

Appendix F – Mental Health and Substance Abuse

Appendix G – Parks and Recreation

Appendix H – Police and Criminal Justice

Appendix I – Tourism Promotion

Appendix J – Transportation

Appendix K – Miscellaneous Revenues

Recommended Resources

1

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Introduction

The foundation of any city government is its fiscal health. The revenues it receives, both present and projected

for the future, set the stage for discussing what services to provide as well as the level of those services –

including the facilities, equipment, and infrastructure that will be needed.

MRSC’s Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns provides information on all the major revenue

sources and most of the minor ones that are available to cities and towns in Washington State. This guide is

intended to help city elected ocials and sta members by providing a comprehensive explanation of the

city’s revenue sources and potential new revenue options to support those services your city has determined

are essential to its taxpayers. This guide is not an administrative manual – for that level of detail, you should

refer to resources such as the Department of Revenue’s Property Tax Levies Operations Manual or the Tax

Reference Manual on State and Local Taxes.

The Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns has been one of MRSC’s core publications for many

years. It was first published in 1992 with an update released in 2009. The current edition was completely

rewritten and re-organized in 2019 to help clarify the multitude of often confusing revenue options, as well as

to include new and additional revenue sources that were not addressed previously.

This publication has been written and researched by MRSC consultants, and any conclusions within this

document are MRSC’s and MRSC’s alone. The primary authors are Toni Nelson and Steve Hawley, with

subsequent contributions by Eric Lowell. Graphics and document assembly have been provided by Marissa

Roesijadi and Angela Mack.

The Center for Government Innovation of the State Auditor’s Oce contributed funding for the 2019 re-write, as

well as valuable review and feedback. We would particularly like to thank Kristen Harris and Sherrie Ard at SAO

for their review and assistance throughout this process. We would also like to thank Alice Ostdiek at Stradling,

Yocca, Carlson & Rauth, P.C. for her review of the property tax chapter, as well as all other individuals who

provided feedback and assistance.

If you have any questions, comments, concerns, or suggestions regarding this document, please contact MRSC.

Table of Contents

2

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

How to Use this Document

MRSC’s Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns is intended to help city sta members and elected

ocials better understand their existing revenue sources and potential options for new revenues. The

document is organized by type of revenue:

• Property taxes

• Sales and use taxes

• Business and utility taxes & fees

• Lodging taxes (hotel/motel tax)

• Real estate excise taxes (REET)

• Other excise taxes

• “State-shared” revenues

• Other revenue sources

• Special taxing districts

There is also an appendix that provides a “menu” of the major revenue sources by program area, such as

transportation revenues, police and criminal justice revenues, or unrestricted revenues.

We also provide a basic history of local taxing powers in Washington, as well as a series of in-depth questions

to help you evaluate potential new revenue sources, whether voted or non-voted.

This document is designed to be viewed electronically or printed as a hard copy. However, viewing this

document electronically will provide you with maximum interactivity and functionality. (We recommend Adobe’s

free Acrobat Reader software program to ensure all features work correctly.)

If you are viewing this document electronically, the table of contents is interactive, which allows you to click on

any topic and go directly to that page. At any time, you can return to the table of contents using the navigation

button at the bottom of each page. Throughout this guide, you will also find many hyperlinks that will take you

to other sections of the document or online resources such as RCWs or helpful resources.

You can also use Ctrl-F (Windows) or Command-F (Mac) to search for specific keywords within this document.

MRSC will update this publication each year as needed to reflect new legislation, changes in interpretation

made by court decisions or Attorney General opinions, and other changes as appropriate. To make sure you

are using the most up-to-date version of this publication, please visit mrsc.org/publications. There is a revision

history near the beginning of this document that summarizes the recent changes.

If you have any questions, comments, concerns, or suggestions regarding this document, please contact MRSC.

Table of Contents

3

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

A Brief History of Local Taxing Power in

Washington

1

Local governments in Washington State do not possess inherent taxing authority and must obtain the authority

to impose taxes and fees from the state constitution and/or statutes adopted by the state legislature.

At the most basic level, there are two categories of taxes in Washington: property taxes and excise taxes.

Property taxes are the oldest form of taxation in Washington and are the largest single revenue source for

many local governments. Excise taxes are the broadest category of taxes and represent all other forms of taxes

except for property tax, with sales taxes being the most significant excise tax for local governments.

The history of local government taxing power in Washington dates back to territorial days, and up until the

early 1930s property taxes were the predominate form of revenue. The first state legislative session in 1890

also authorized first, second, third, and fourth class cities to impose business license taxes, and by 1932

Seattle was levying an occupation tax which is believed to be the first instance of a city imposing a business

& occupation (B&O) tax.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, significant changes were made to the array of taxes that were

imposed by Washington State, some of which significantly impacted local government. The first change was

placing a limit on the cumulative rate of property taxes that could be imposed upon the taxpayer in any given

year – people’s Initiative 64, which reduced property taxes by almost 50%. This resulted in the second most

significant change in state taxing power – the imposition of a variety of excise taxes. The Revenue Act of 1935

reduced the state’s dependency upon property tax by authorizing a wide array of excise taxes, including a

retail sales tax and new business and occupation taxes.

However, this additional excise authority was only granted to the state. It was not until 1970 that the state finally

provided legislative authority to cities and counties allowing them to impose a sales and use tax of 0.5% for

general local government purposes. In 1982, the legislature authorized cities and counties to impose a second

0.5% on retail sales for general government purposes, resulting in a combined total of 1% that is still in place

today. During this same legislative session, there were new restrictions placed on cities’ authority to impose

B&O and utility taxes. These significant changes in taxing authority provided many local governments with

opportunities to diversify their revenue streams.

Over the course of the past several decades, the state legislature has authorized cities and towns to impose

other sales taxes and excise taxes for specific purposes, all of which will be discussed in the following pages of

this Revenue Guide.

Property taxes and excise taxes are imposed dierently – property taxes are based upon changing property

values and must be re-calculated and re-imposed every year, while excise taxes, once adopted, remain in eect

on all taxable events that occur now and in the future.

Property taxes have also seen a number of additional restrictions over the past century, beyond the cap on

the cumulative property tax rate adopted in the 1930s. In 1971, a “106% levy lid” on property tax increases from

1 This information comes primarily from The Closest Governments to the People: A Complete Reference Guide to Local

Government in Washington State, by Steve Lundin and edited by the Division of Governmental Studies and Services at

Washington State University. A copy of the full document is posted on the MRSC website.

Table of Contents

4

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

one year to the next was enacted, which limited the total amount of property tax revenue local governments

could generate each year. In 2001, voters approved Initiative 747, ultimately resulting in legislation that

reduced the limit on annual increases for property tax levies to 1% – also known as the “101% levy lid,” which

is still in eect today.

In addition to property taxes and excise taxes, many analysts recognize a third category of taxes: income

taxes, which have been imposed by the vast majority of states as well as a number of cities around the

country. However, income taxes are not currently used at either the state or local levels in Washington. At the

same time that voters placed the first restrictions on property taxes during the Great Depression, voters also

approved a statewide graduated income tax (Initiative 69). However, a divided state Supreme Court soon

struck the initiative down as unconstitutional, ruling that an income tax was a property tax and that, as such,

a graduated income tax violated the uniformity clause of the state constitution.

2

Later attempts to establish

an income tax were also unsuccessful. In 1984, the state legislature enacted RCW 36.65.030, which prohibits

any city or county from levying a tax on “net income,” and in response to a proposed voter initiative in 2024,

the legislature enacted RCW 1.90.100 which prohibits the state, counties, cities, or other local jurisdictions from

taxing any individual person on any form of personal income.

Local government revenues have evolved significantly throughout Washington’s history and continue to do so

today. This Revenue Guide provides the most current and up-to-date information, but each legislative session

brings new thoughts, ideas, and concepts that result in changes and additional options. We will update this

guide as needed to reflect those changes.

2 This interpretation has been criticized by legal scholars.

Table of Contents

5

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Key Considerations for Evaluating

Revenue Sources

There are several factors to consider when analyzing if it’s in the city’s best interests (both fiscal and political) to

impose new taxes and fees. Local governments cannot necessarily provide all of the services requested by the

public, and of all the revenue options available, there are some that will meet your city’s goals and objectives

and others that will not.

To that end we have provided a list of key questions to consider when identifying and evaluating potential

revenue sources. Answering these questions can help you more clearly articulate your city’s revenue goals.

• What do you need the revenue for? Some revenue sources are unrestricted and may be used for any lawful

governmental purpose. Others are restricted to specific purposes under state law. Some may be imposed

permanently, while others are temporary. Are you looking to increase your general fund (current expense)

budget or pay for basic governmental services, operations, or maintenance? Creating a new program or

preparing for a major capital project? Bridging a temporary revenue shortfall or replacing lost funding? Are

you planning to supplant (replace) existing funding and re-structure how a program is financed? If so, make

sure you read the statutes carefully, as some revenue sources specifically restrict or prohibit supplanting.

• How much revenue do you need to generate? Your local revenue capacity depends on factors such as

statutory limitations, your local economy, and your demographic profile. For instance, is your city largely

residential, or does it have lots of businesses and retail sales? Do you have hotels and tourist attractions?

How active is your real estate market?

• Who will pay and who will benefit? Will the taxes or fees be paid by local property owners? Businesses

and utility companies? Shoppers? Tourists? Real estate buyers and sellers? Vehicle owners? Property

developers? Will the revenue source result in an overall tax increase, or is it a credit against an existing

state or county tax? Who will benefit from the additional spending?

• Do you need voter approval? If so, you must plan ahead and consider additional factors such as election

timing, election costs, and voter turnout as described on the next page.

• When do you need the revenue? Some revenue sources have certain deadlines set by state statute. For

instance, property taxes may only be levied once a year and must be certified to the county assessor by

November 30 for the forthcoming year, while sales tax rates may only change on January 1, April 1, or July

1 and the state Department of Revenue must receive notice at least 75 days in advance. You may have to

wait several months before you start receiving these additional revenues, or longer if you time it poorly. It

pays to include this analysis in your planning process.

• Is the revenue source subject to possible referendum? You can’t please everyone, but presumably you

need a certain level of support from local residents or businesses. If your city has adopted powers of

initiative and referendum, some revenue sources could be subject to referendum. Even if your city or town

does not have powers of initiative and referendum, some revenue options are still subject to referendum

as prescribed by statute.

• What are the limitations? For instance, property tax revenues are generally limited to a 1% annual

increase, even if your assessed valuation is increasing faster than 1%, and certain property tax levies could

potentially be reduced through prorationing. Sales taxes have no such limitations but can be significantly

Table of Contents

6

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

impacted during economic downturns. And “state shared” revenues could be reduced or eliminated during

any legislative session, particularly if state revenues are declining.

• Are there any unique statutory requirements? Some revenue sources may have other specific statutory

requirements – for instance, requiring revenue sharing with the county, requiring the creation of an

advisory committee, establishing a slightly dierent tax base than usual, etc.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS FOR VOTED REVENUE SOURCES

If your revenue source requires voter approval, there are additional considerations, such as:

• When is the filing deadline? For voted revenue sources, you must consider not only the notification

deadlines (such as certifying property taxes to your county assessor and notifying DOR of sales tax rate

changes), but also the election dates and filing deadlines discussed below.

To ensure timely receipt of funds, you must work backwards. For instance, if you want to increase next

year’s property tax revenues through a levy lid lift: property taxes must be certified to the county assessor

no later than November 30, which means the levy lid lift must appear before voters no later than the

general election in early November, which means you must file notice with the county auditor no later than

the date of the primary election in early August. If you wait for “budget season” in August or September to

start considering the levy lid lift, it will be too late – you will have missed the deadline, and any potential

receipts from the levy lid lift will be delayed for an entire year.

For a summary of the various deadlines, see Key Deadlines for Voted Property Taxes and Sales Taxes.

• What are the approval requirements? Does the ballot measure require a simple majority (50% plus one),

such as a sales tax or levy lid lift? Or does it require a 60% supermajority, like bond measures, excess O&M

levies, and certain EMS levies? Are there minimum validation (voter turnout) requirements?

• When should the measure appear on the ballot? There are four possible election dates for local

governments in Washington – special elections in February and April, the primary election in August, and

the general election in November (RCW 29A.04.330). Most measures may appear on the ballot at any one

of those elections, but there are a couple exceptions (such as public safety sales taxes, which by statute

may only appear at a primary or general election).

Voter turnout will almost certainly be highest in November and lowest in February and April, and the

composition of the electorate may dier for some jurisdictions. Election timing may also aect election

costs and the timing of receipts.

• What other measures or candidates are appearing on the ballot? Ask around to find out what other ballot

measures may be appearing before your city’s voters. It’s possible you might not want to go head-to-head with

certain ballot measures, as voters may not like voting on too many taxes at the same time. Alternatively, you

might want to “ride the coattails” of a popular measure or candidate by appearing on the same ballot.

• How have other ballot measures fared recently? You can research local ballot measures across the

state at MRSC’s Local Ballot Measure Database, which we update after every election once counties

certify the results. For revenue measures, you can filter by statutory authority (sales taxes, property

taxes, levy lid lifts, etc.), government type (such as city or county), subject (fire protection, libraries,

aordable housing, etc.), or even by county. You may want to contact jurisdictions that have attempted

similar measures to gain their insight.

Table of Contents

7

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

• What will you do if the ballot measure fails? Will you abandon your attempt or go back to the drawing

board? Will you be forced to cut services or lay o employees? Will you submit a scaled-back version to

voters in the hopes they will pass it next time?

Or will you submit the exact same measure to voters a second time, in the hopes that the result will be

dierent due to changes in turnout, the composition of the electorate, enhanced public outreach by support

groups, or news media coverage? For instance, some jurisdictions that place an item on the primary election

ballot will file an identical (or very similar) resolution for the November general election. If the measure

succeeds in August it is simply removed from the November ballot, but if it fails it will appear before voters

again in November. It is not uncommon for a ballot measure that failed by several percentage points in a

special or primary election to pass in the next general election, although passage is certainly not guaranteed.

• How much will the election cost? It costs money for counties to administer elections, and counties pass

those costs along to the jurisdictions holding the elections (see RCW 29A.04.410). These costs include

postage and printing for the ballots and voters’ pamphlets, temporary election workers and stang,

supplies, transportation, required elections notices, and administrative overhead costs.

If your city already has other city measures or candidates on the same ballot – such as city council/mayoral

elections, which typically occur at primary and general elections in odd-numbered years

3

– the additional

costs for a ballot measure will be minimal. But if the city does not have other measures or candidates on

the ballot and would not otherwise be conducting an election, the election costs will be significantly higher.

Election costs may also vary depending on whether you are submitting the measure at a special, primary,

or general election. For example, special election costs may be higher than primary or general election

costs because there are typically fewer local governments participating in special elections and sharing the

costs. Contact your county auditor to get estimates.

• What are the ballot title requirements? The ballot title is the actual text of the measure that will appear on

voters’ ballots. The ballot title must be written by the city attorney and must comply with RCW 29A.36.071

regarding ballot title composition and length. However, some revenue sources have additional ballot title

requirements set by statute.

• Will your city prepare informational materials? RCW 42.17A.555 prohibits city elected ocials and

employees from using “public facilities” to promote or oppose any ballot proposition. Broadly speaking, this

means city sta and ocials cannot support or oppose a ballot proposition during work hours, within their

ocial capacities, or using city supplies, equipment, funds, or facilities. However, cities may prepare and

distribute fact sheets or other informational materials for voters if such information is fair and objective and

the city shares the information via normal, customary means of providing information. For more information,

see our webpage on Use of Public Facilities to Support or Oppose Ballot Propositions.

3 City ocials are elected in odd-numbered years pursuant to RCW 29A.04.330.

Table of Contents

8

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

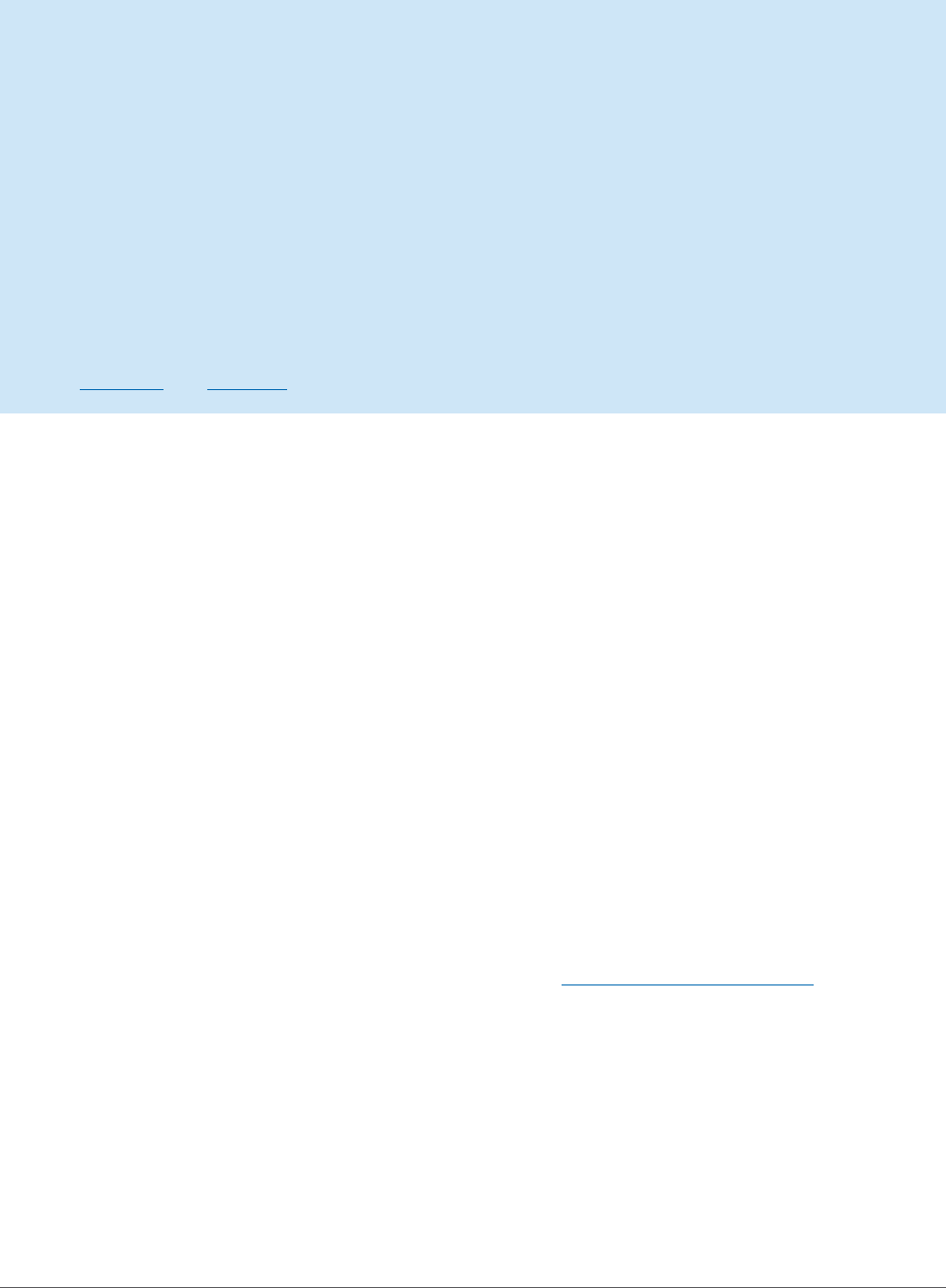

KEY DEADLINES FOR VOTED PROPERTY TAXES AND SALES TAXES

As mentioned previously, if you are considering a voted revenue increase you must plan ahead and keep the

various statutory requirements and deadlines in mind. Here are key dates to remember.

• Property tax levies are set on an annual basis. All city property taxes for the upcoming year must be

certified to the county assessor no later than November 30 (RCW 84.52.070).

• Sales tax rate changes may only take place on January 1, April 1, or July 1, and may not take eect until 75

days after the state Department of Revenue receives notice of the change (RCW 82.14.055).

The election dates and filing deadlines are established by RCW 29A.04.330. To place an item on the ballot

for the February or April special elections, your jurisdiction must file the resolution at least 60 days before the

election date. For the primary election, you must file the resolution no later than the Friday immediately before

the first day of regular candidate filing in May. And for the general election, you must file the resolution no later

than the date of the August primary election.

Below is a quick summary, assuming the county promptly notifies DOR of any sales tax changes and certifies its

levy to the county assessor by November 30.

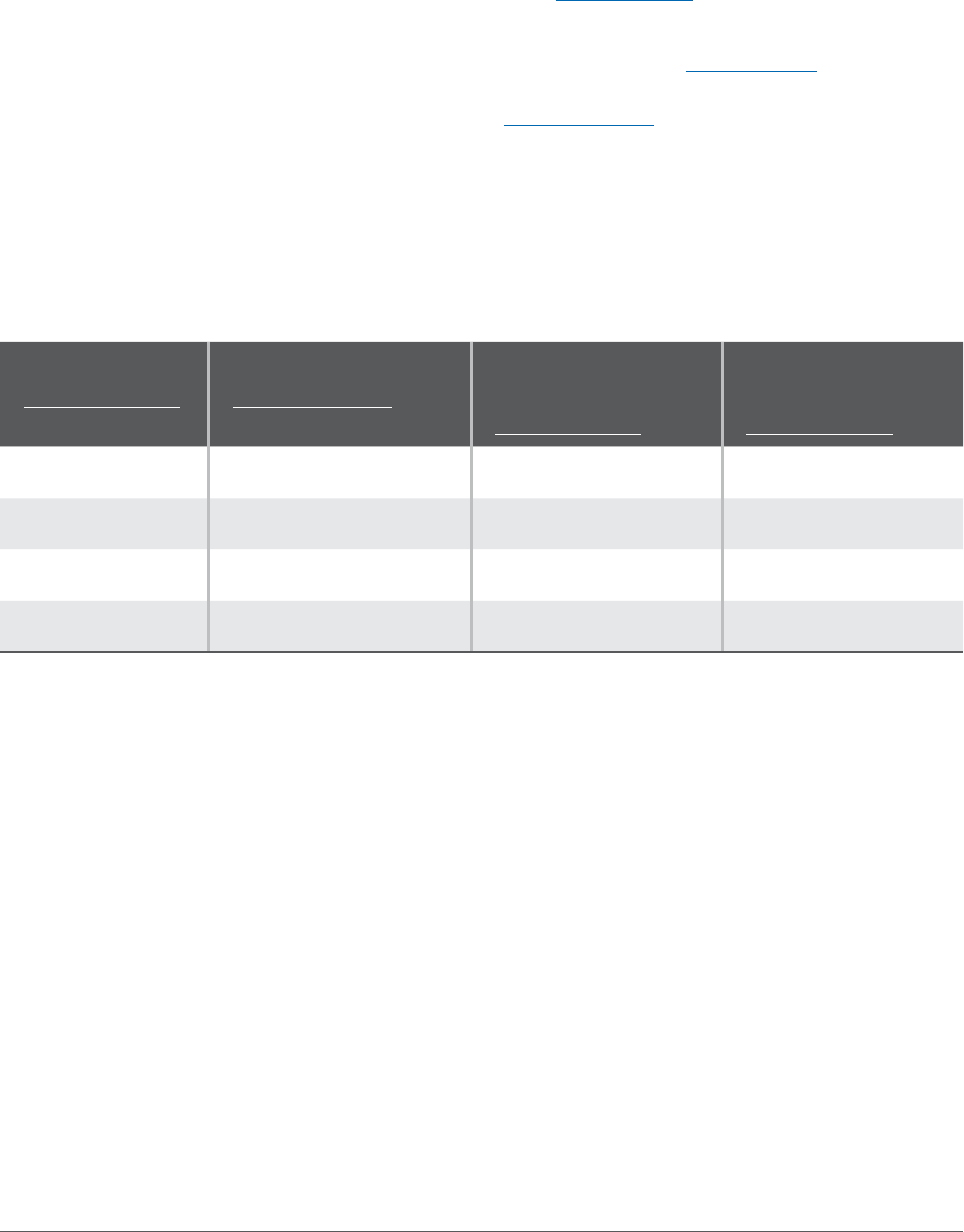

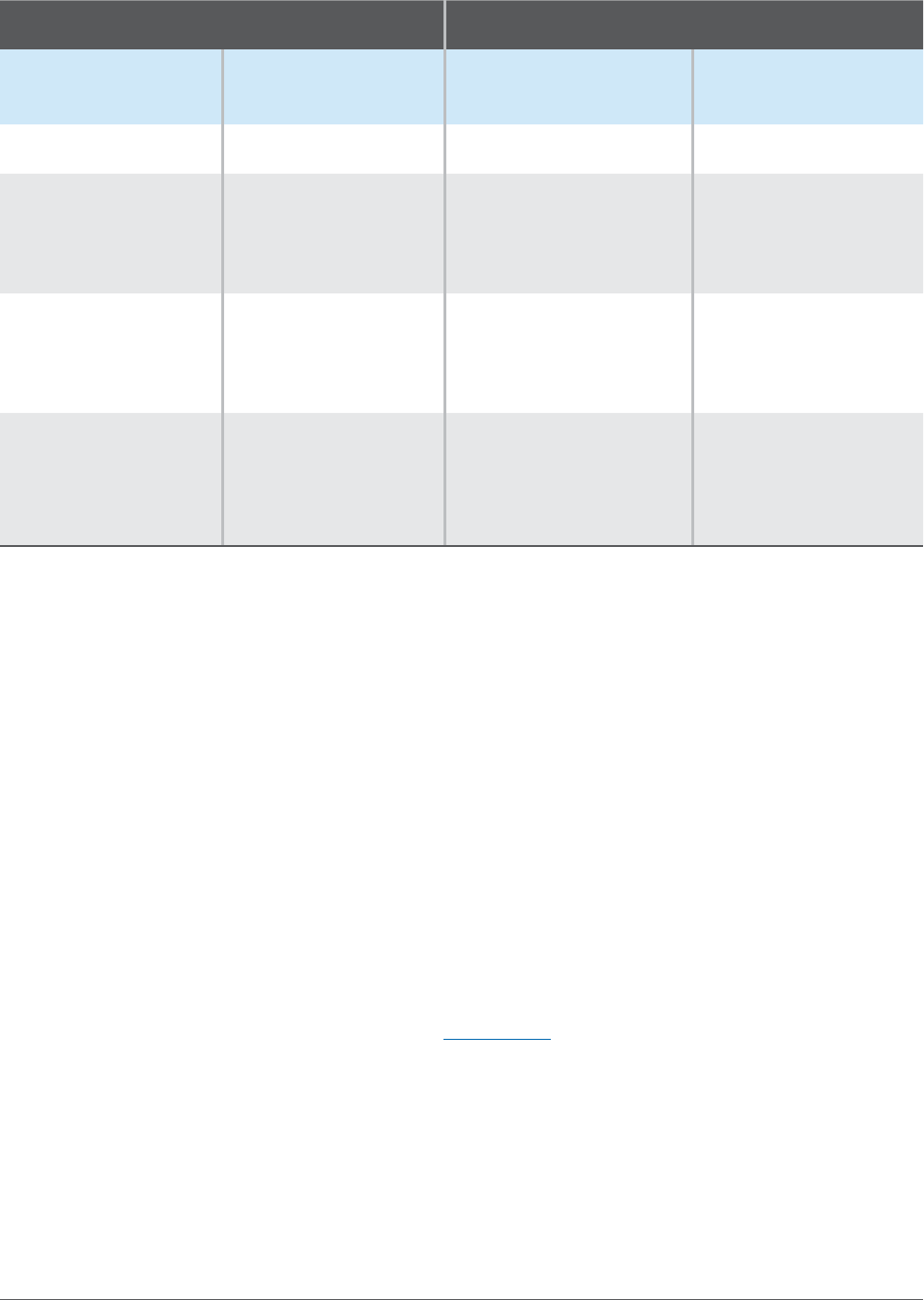

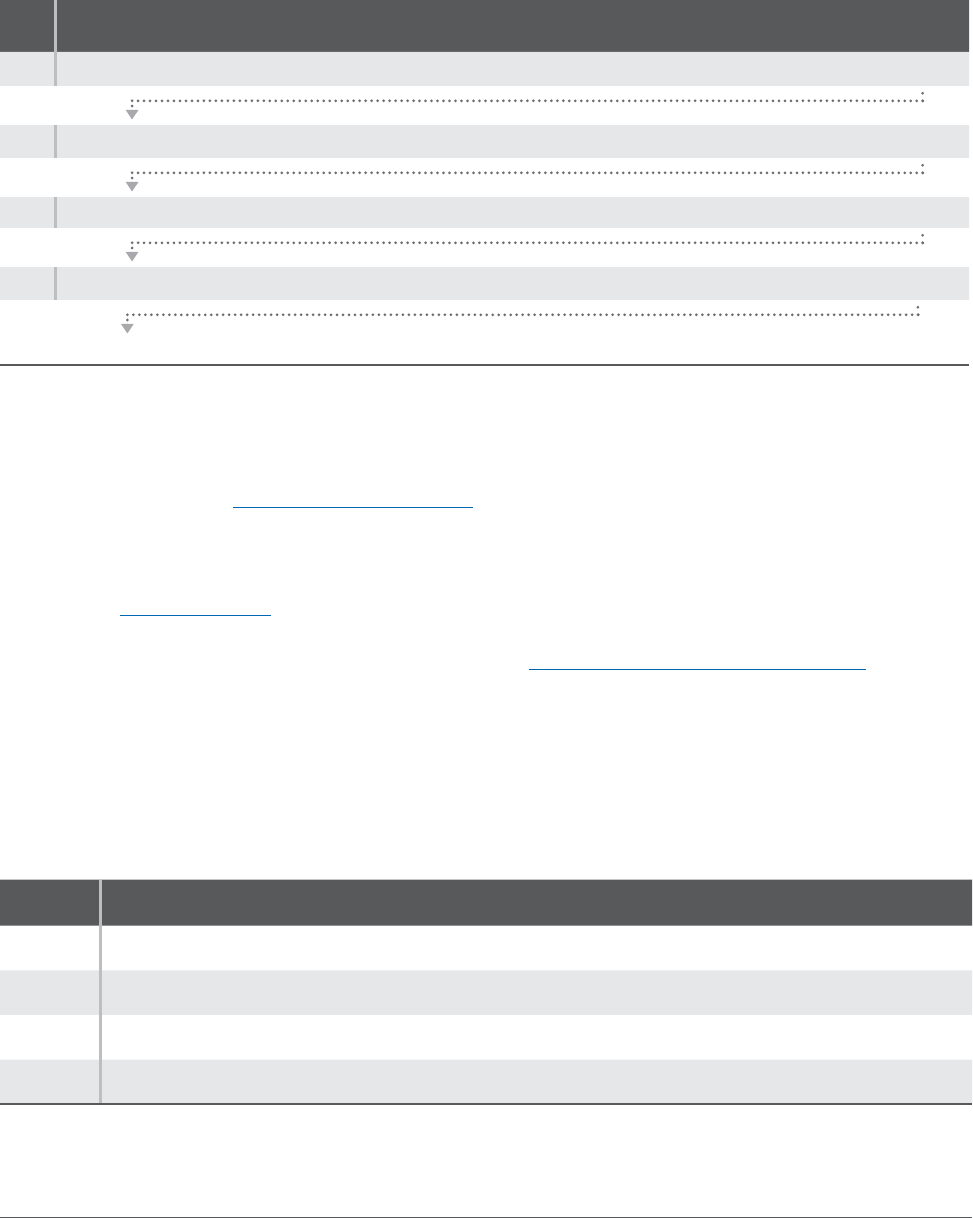

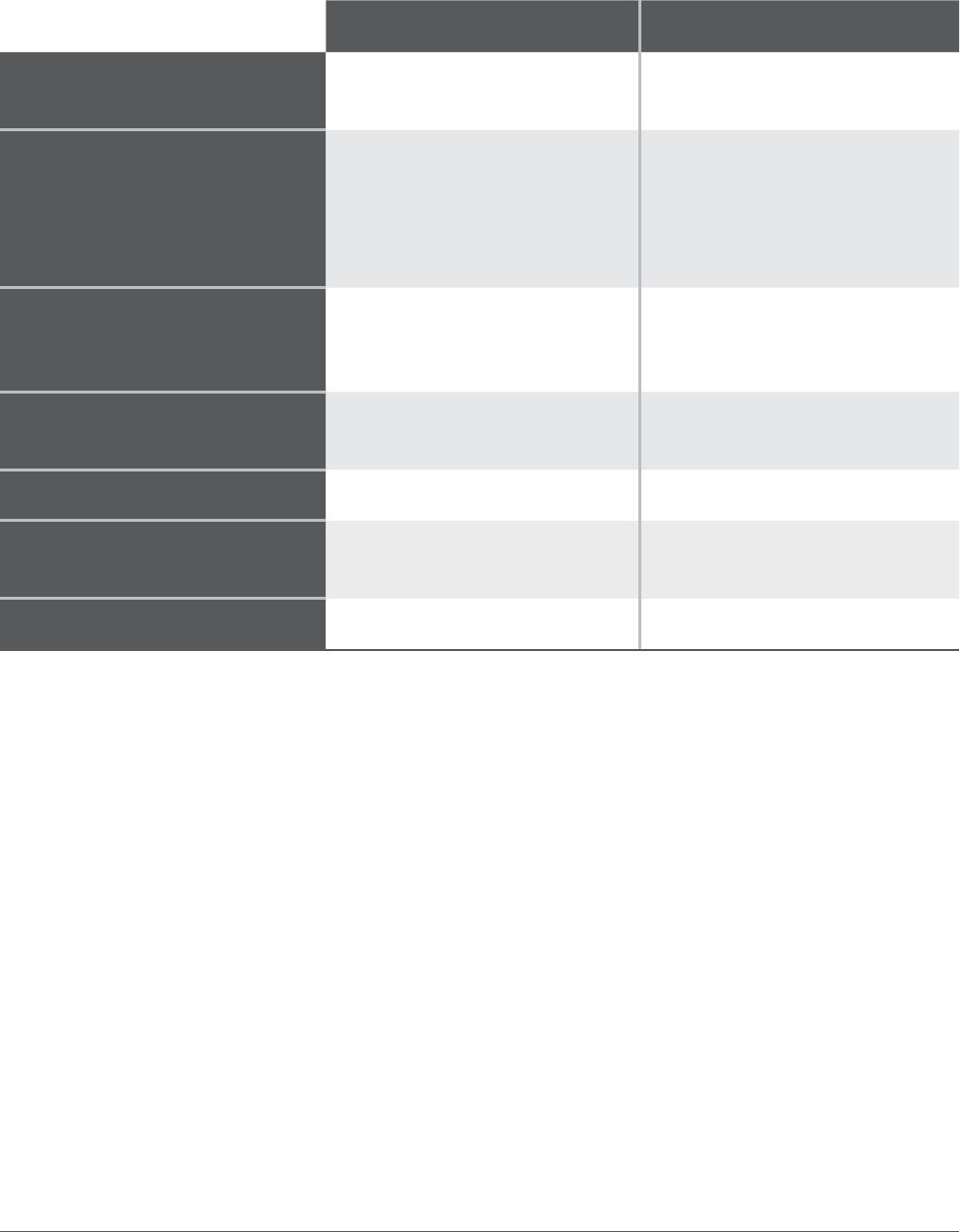

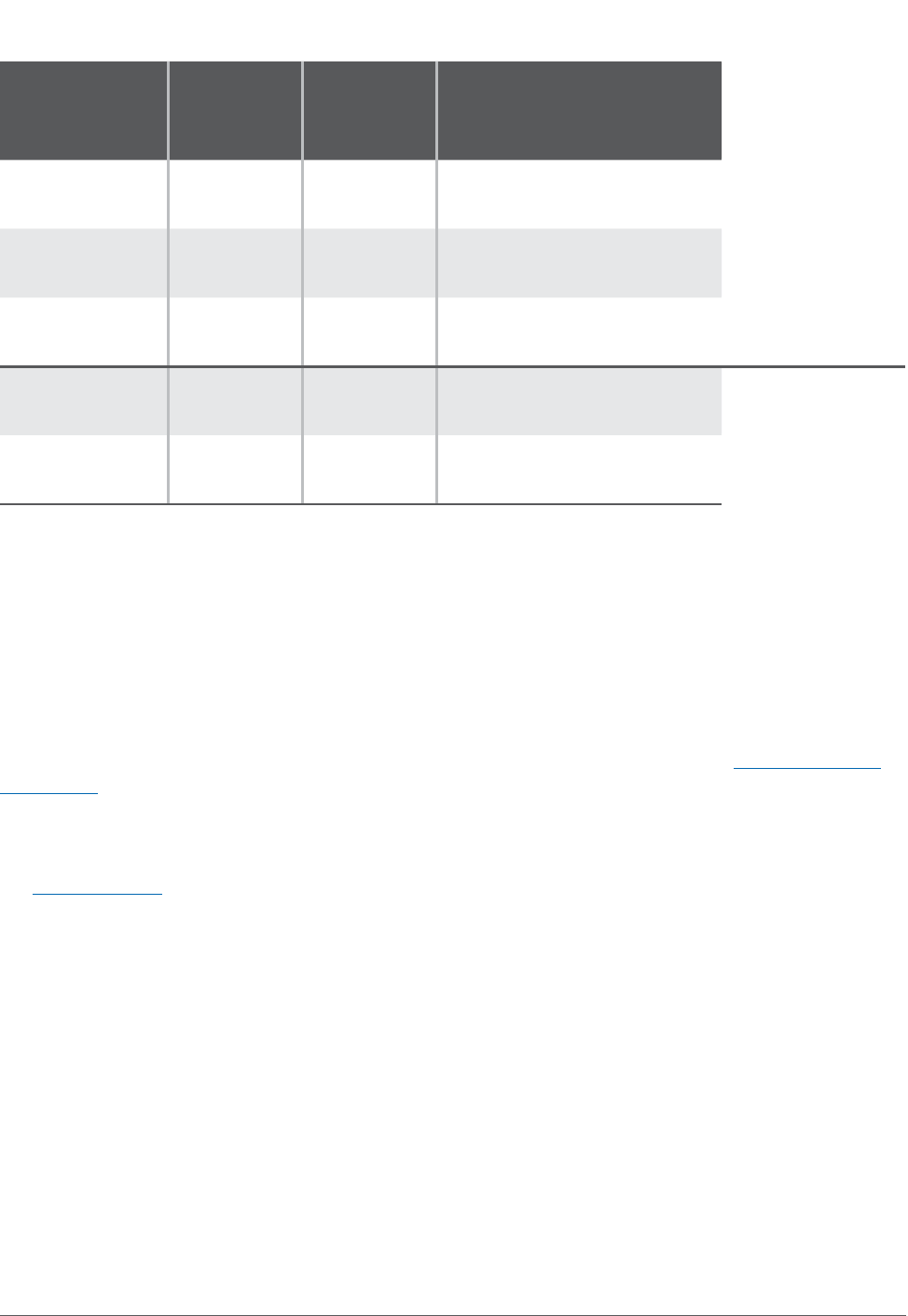

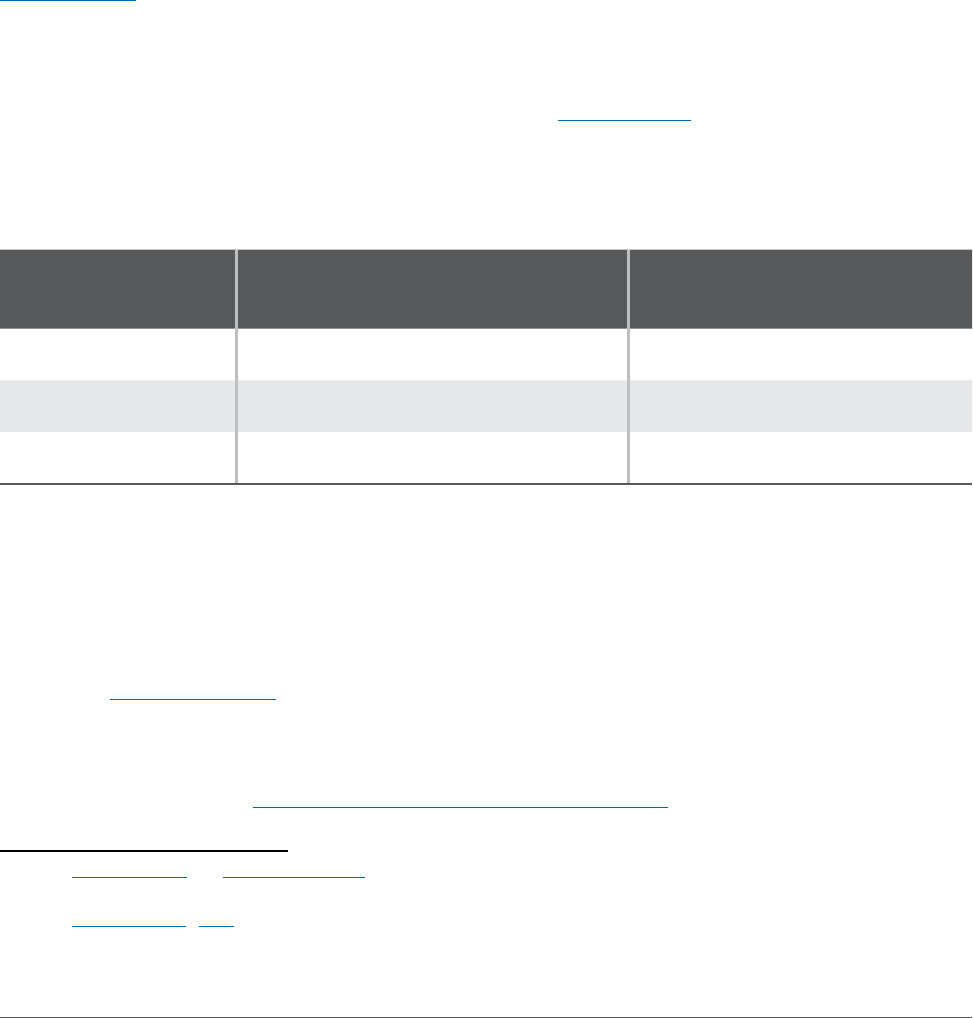

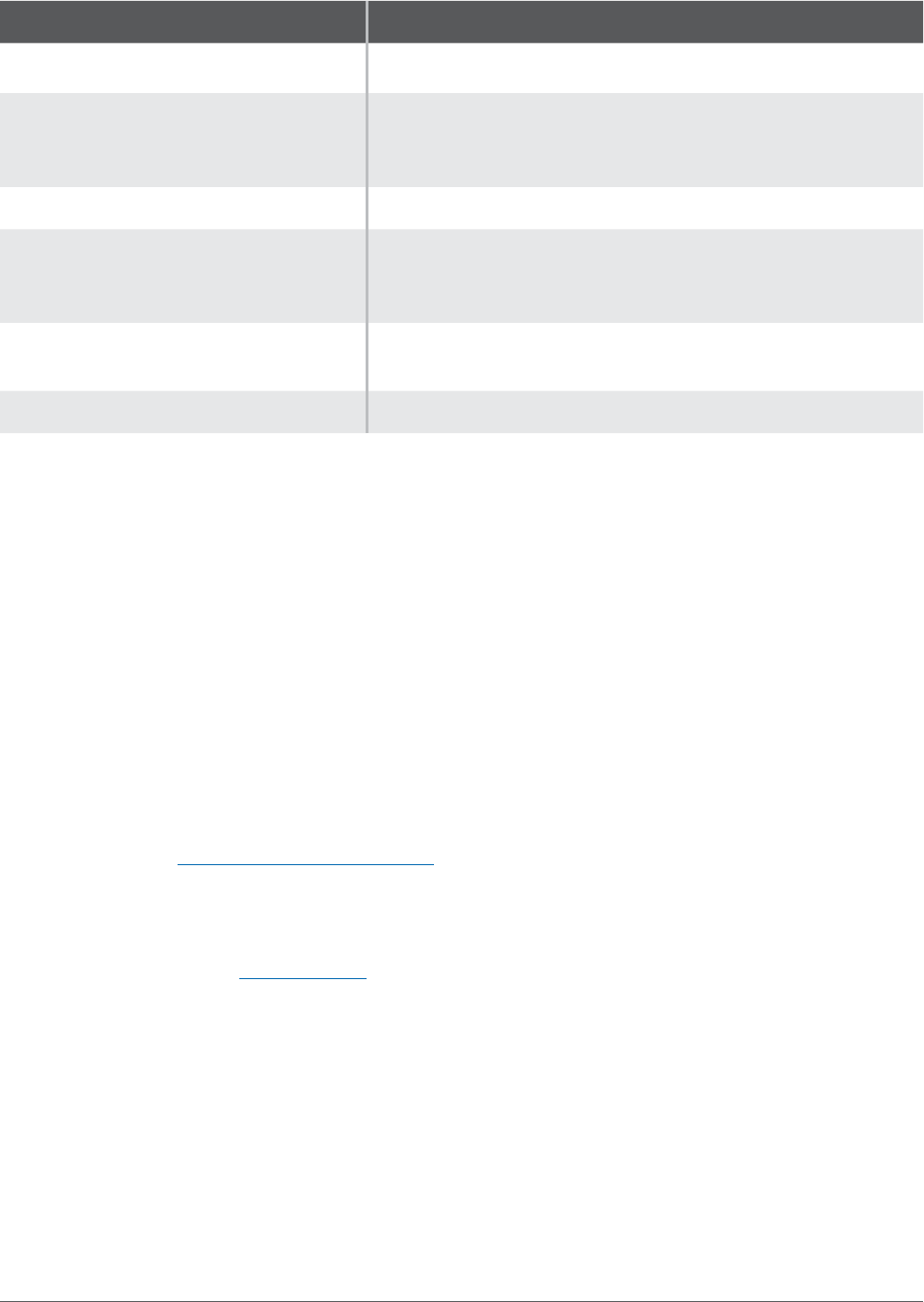

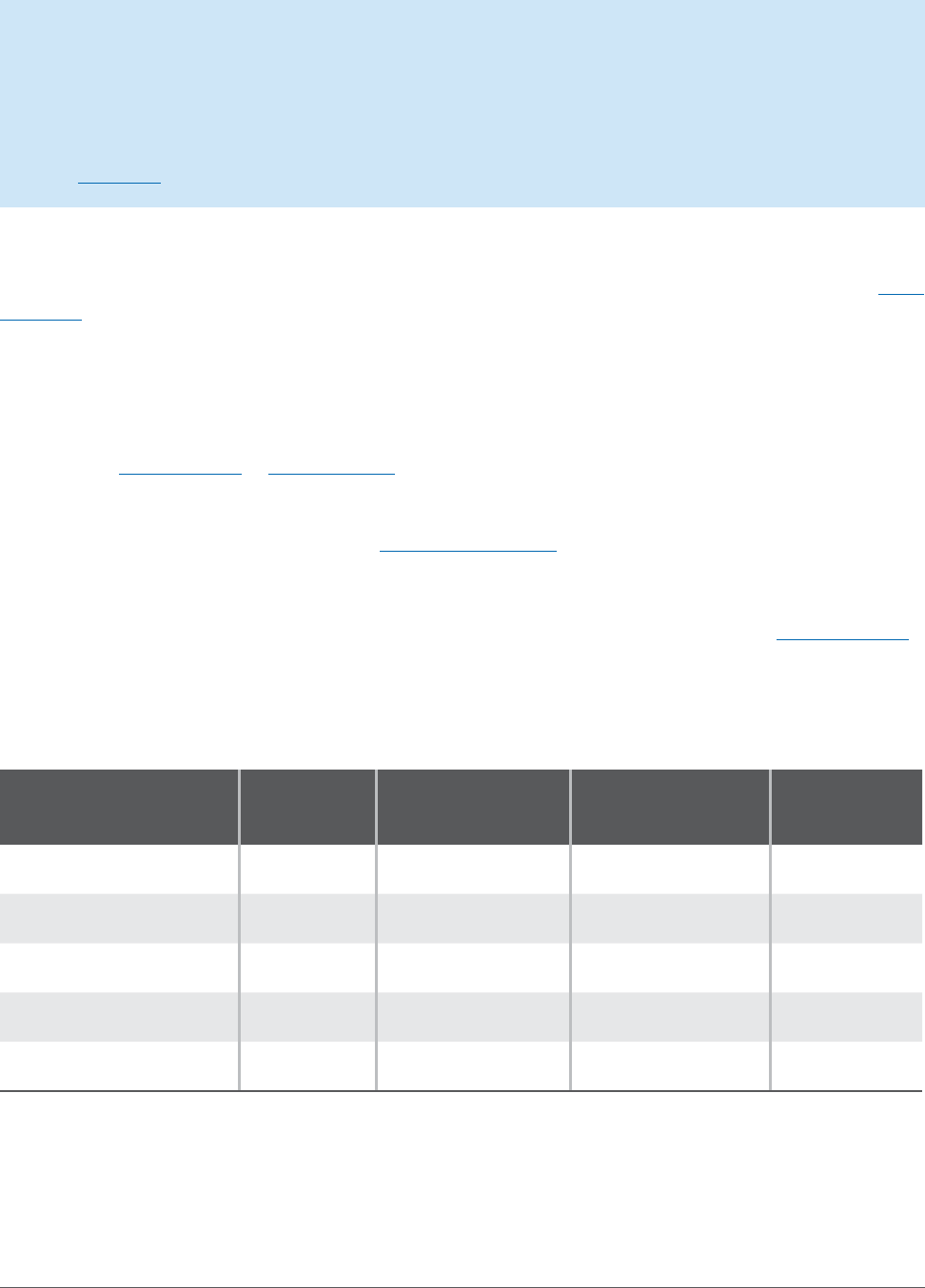

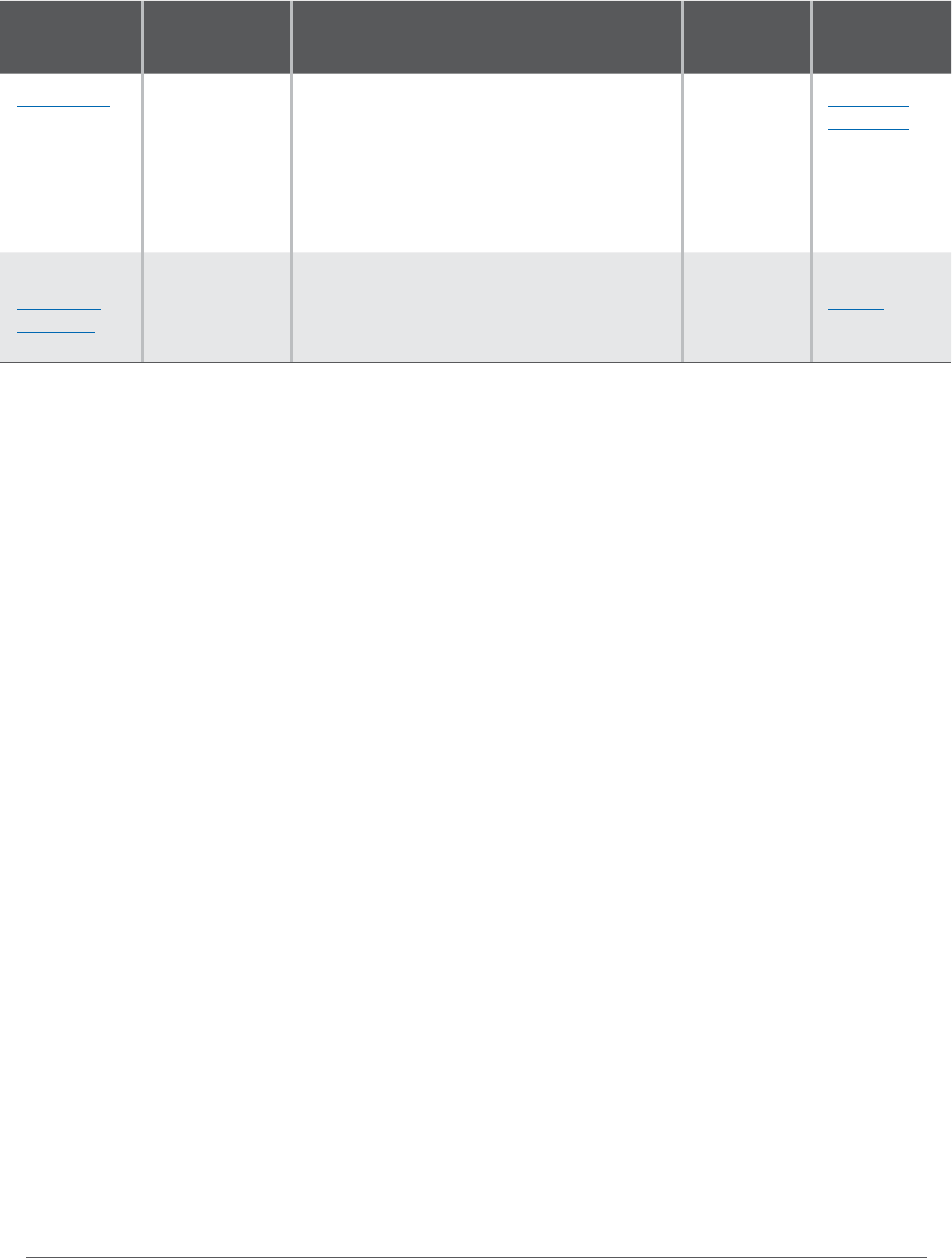

Election

(RCW 29A.04.330)

Filing deadline

(RCW A..)

Approved sales tax

increases take eect

(RCW ..)

Approved property tax

increases take eect

(RCW ..)

February special Early-to-mid December July 1 of election year Next year

April special Late February January 1 of next year Next year

August primary Early-to-mid May January 1 of next year Next year

November general Date of August primary April 1 of next year Next year

Table of Contents

9

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Property Taxes

Property taxes are, for many cities, the primary source of revenue. Most of a city’s property tax revenue comes

from its general fund levy, which may be used for any lawful governmental purpose, but cities also have a few

additional property tax options that may only be used for certain restricted purposes. This chapter will discuss

the property tax authority provided to cities and towns.

Washington’s “budget-based” property tax structure is very complicated. We plan to limit our discussion of

property taxes to what city ocials and sta members really need to know in order to develop property tax

levy projections and to consider potential options, and even that is pretty complicated.

For a for a more detailed look at property taxes, refer to the state Department of Revenue’s Property Tax

Publications, and particularly the Property Tax Levy Manual.

WHAT IS A BUDGETBASED PROPERTY TAX?

Perhaps the most important concept to understand regarding Washington’s property tax system is that it is a

“budget-based” property tax.

This means that cities and other taxing districts, as part of their annual budget process, must first establish the

total dollar amount of property tax revenue they wish to generate for the upcoming year, subject to several

restrictions. Once the total dollar amount is established, the county assessor calculates the levy rate – the rate

that each property owner must pay – based on the total assessed valuation of all properties.

This “budget-based” process is the reverse of most other states in the country. Almost every other state

uses a “rate-based” property tax system, in which governments establish the levy rate that each property

owner must pay, which is then multiplied by the assessed value to determine the total dollar amount of

revenues generated.

There are three main components to the property tax calculation: the levy amount, the assessed value, and

the levy rate.

Levy Amounts vs. Levy Rates

To understand this budget-based system, and in particular the various limitations on how much property tax

revenue local governments can generate, it is extremely important to understand the dierence between levy

amounts and levy rates. Some limitations are based on levy rates, while others are based on levy amounts, and

the two are often confused.

The levy amount – sometimes referred to as simply the “levy” – is the total dollar amount of property taxes to

be collected in one year. In the example on the next page, the levy amount is $1 million.

The levy rate is how much any individual property owner owes, expressed as a dollar amount per $1,000

assessed value. In the example, the levy rate is $2.50 per $1,000 assessed valuation.

Table of Contents

10

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Under the budget-based system, the city establishes its desired levy amount first, and then the county assessor

uses the assessed valuation (discussed in more detail below) to calculate the subsequent levy rate. This

formula is expressed as:

Levy Amount ÷ (Assessed Value ÷ 1,000) = Levy Rate per $1,000 AV

For example:

Levy amount requested by city

for general fund

÷ (Citywide assessed value ÷ 1,000 = Levy rate

$1 million

÷

($400 million ÷ 1,000 = $400,000)

=

$2.50 per $1,000 AV

However, there are multiple restrictions placed on how fast the levy amount can increase, as well as maximum

levy rates for individual levies (such as general fund levies or EMS levies) and maximum aggregate (combined)

levy rates. These restrictions are all intended to protect citizens from excessive taxation, but they also limit

the amount of property tax revenue that local governments can generate. The property tax process can be

complicated and confusing, but we will do our best to explain it in more detail throughout this chapter.

Assessed Value

The other primary factor in determining the levy rate each year is the assessed value. Property taxes are

assessed and collected at the county level. The amount that each property owner pays, and the total property

tax revenue a city can generate, depends in large part on the value of the properties within the city, known as

the assessed value or assessed valuation and commonly abbreviated as AV or A/V.

The assessed valuation is the true and fair value as provided in Article VII, §2 of the WA State Constitution and

further defined in Chapter 458-07 WAC, which states that “true and fair value” means market value and is the

amount of money a buyer of property would pay to a willing seller.

The county assessor’s oce is responsible for assessing all property located wholly within the county, including

both the incorporated areas (cities and towns) and the unincorporated areas of the county. In determining true

and fair value, the assessor may use a sales (market data), cost, or income approach, or a combination of the

three approaches (WAC 458-07-030). In addition, the state Department of Revenue is responsible for assessing

intercounty, interstate, and foreign utility company property (known as state-assessed utilities).

Counties must update assessed valuations for all properties every year, with physical inspections of each

property at least once every six years (RCW 84.41.030 and 84.41.041). Most counties conduct inspections on a

six-year cycle, meaning that they inspect roughly one-sixth of the properties within the county each year and

update their assessed values accordingly. A few counties use a four-year inspection cycle and inspect roughly

one-quarter of the properties each year.

4

The annual revaluations in between each inspection are estimates

based on statistical analysis and market data.

4 As of 2024, 37 counties inspected properties on a six-year cycle, while two counties (Chelan and Ferry) used a shorter

four-year inspection cycle.

Table of Contents

11

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

The levy rate for any taxing district must be uniform for each property within its boundaries (article VII, section

2 of the Washington State Constitution). That is to say, a city’s general fund levy rate per $1,000 AV must be the

same for each property within the city.

5

State law also establishes a separate valuation system for certain agricultural, timber, and open space land

based on “current use” value, which is lower than the “true and fair value.”

6

In addition, all properties owned by

federal, state, tribal, and local governments (municipal corporations); public and private schools; and churches

are exempt from property taxes.

The county assessor must notify each taxing district within the county, including every city and town, of its total

assessed value before the levy certification deadline, so the taxing district can calculate its levy amounts for

the upcoming year and certify them to the county assessor by (see Annual Levy Certification Process).

5 However, there may be some exceptions for senior, disabled, or low-income residents. There are also certain tax

abatement programs that reduce a property’s taxable value to provide financial incentives for economic development or

historic preservation.

6 Current use values are permitted under article VII, section 11 of the Washington State Constitution. See also chapter 84.34

RCW and chapter 458-30 WAC.

Table of Contents

12

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

MAXIMUM AGGREGATE LEVY RATES

There are several dierent limitations on the maximum levy rate (per $1,000 AV) that cities and other local

governments may impose on property located within their jurisdiction. Some of the limits are aggregate and

limit the total property tax burden on property owners, while others establish maximum levy rates for specific

types of levies such as the city general fund levy or EMS levies.

This section will discuss the aggregate (total combined) levy limitations. The rest of the property tax chapter

contains information on the various types of levies and their maximum levy rates.

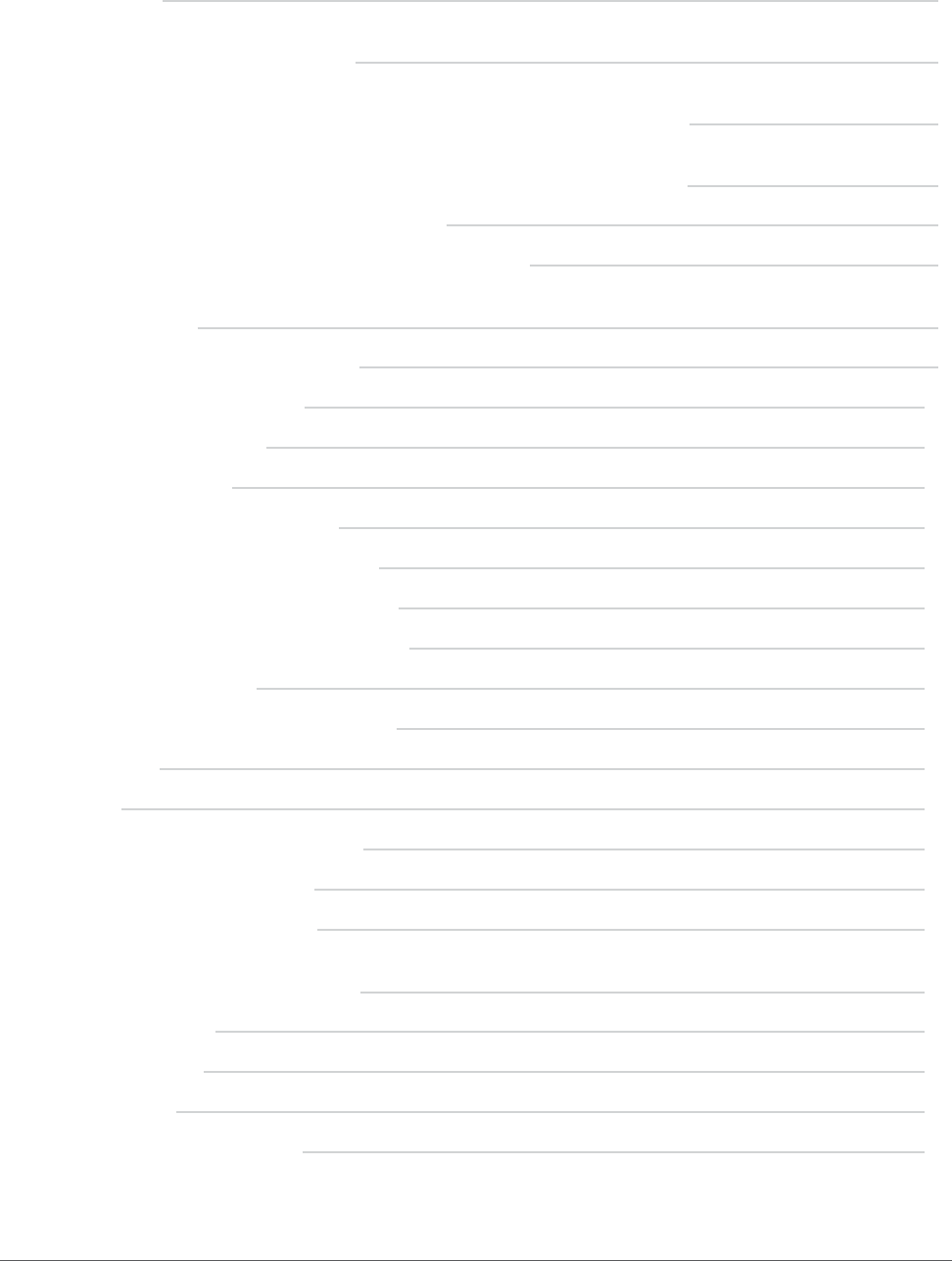

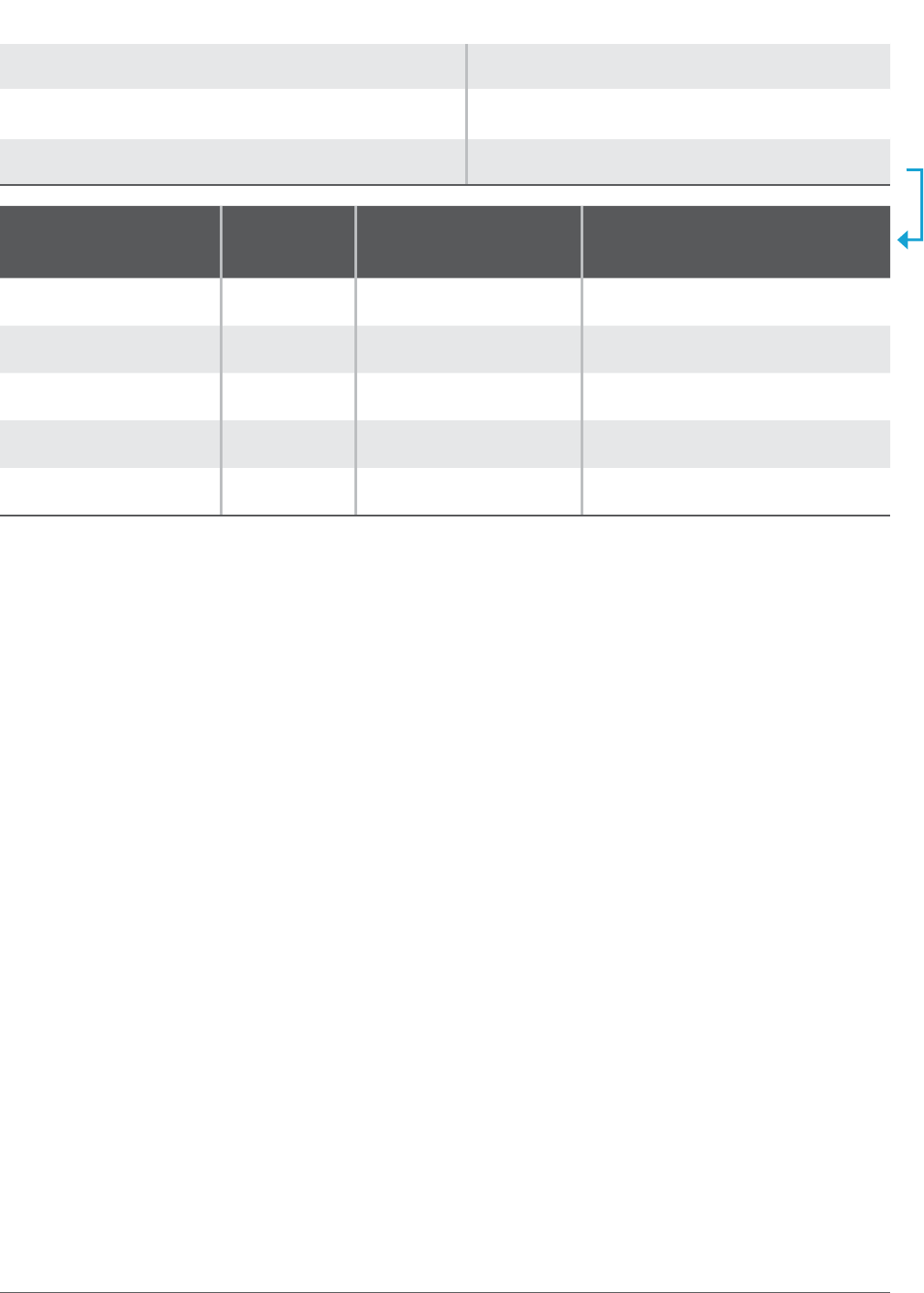

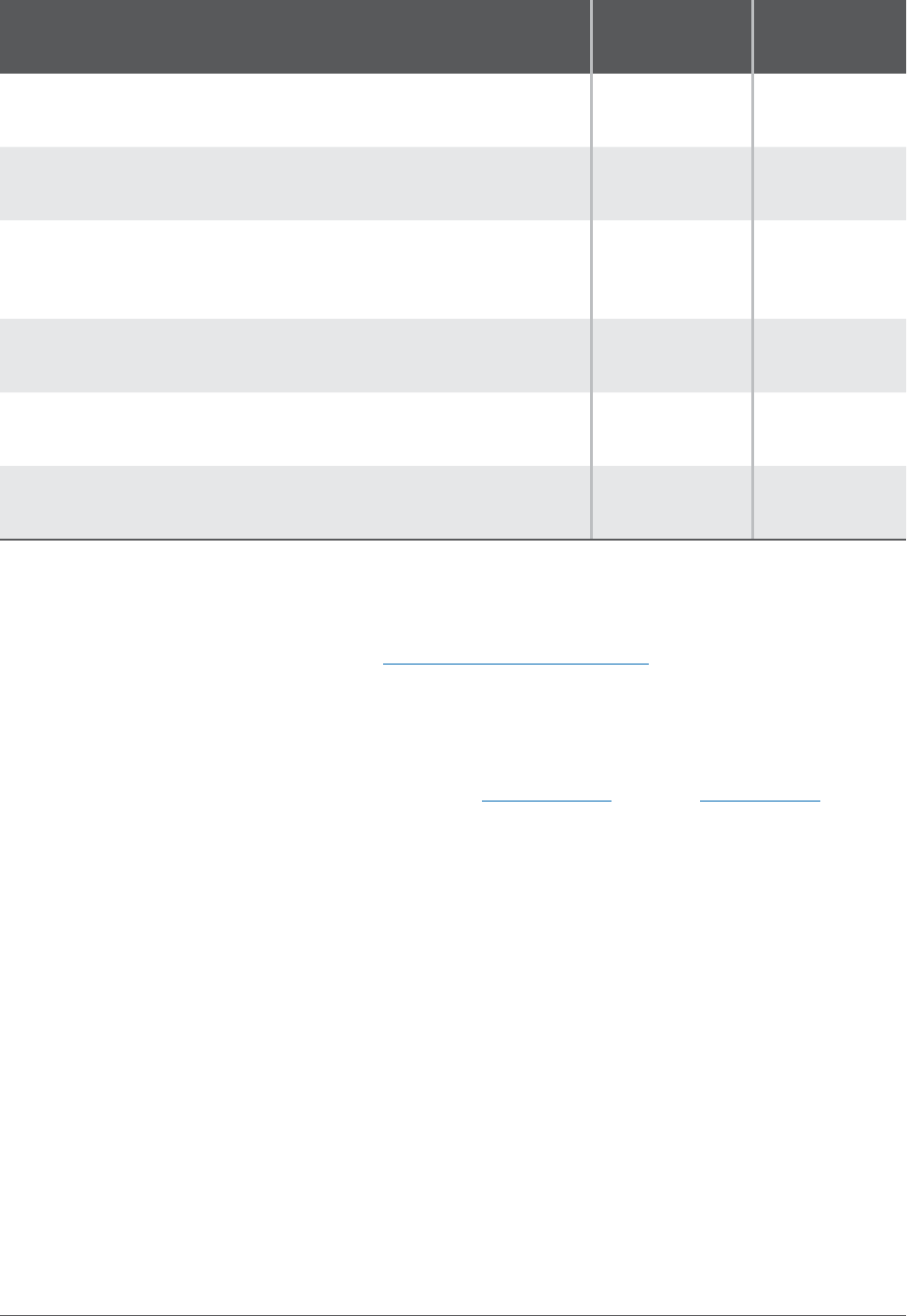

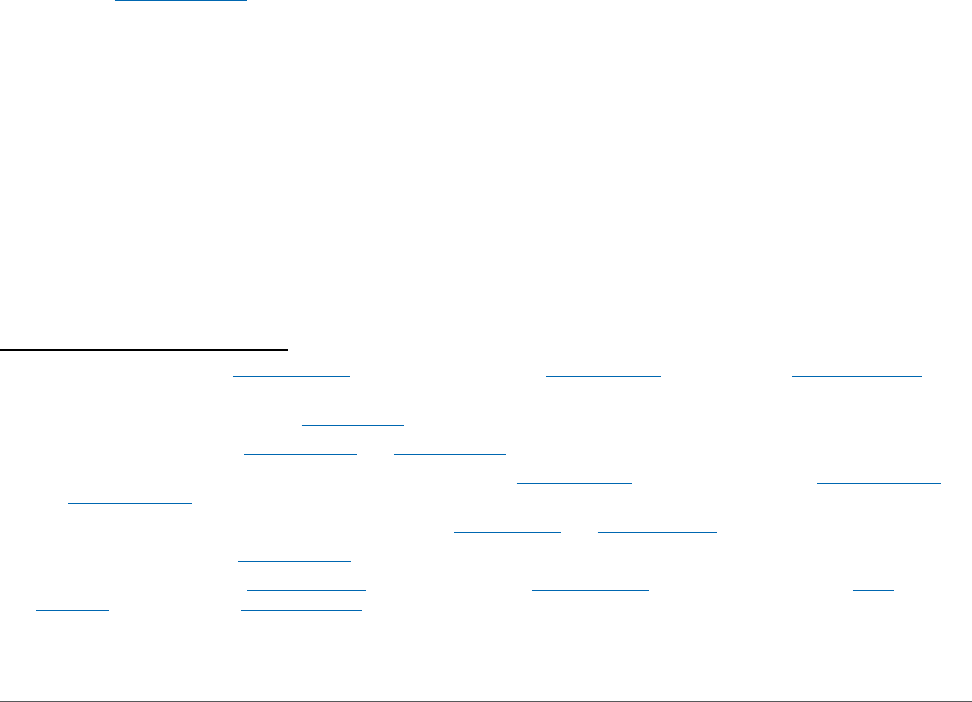

Tax Code Areas

To understand maximum aggregate levy rates, it is important to understand the relationship and dierence

between “taxing districts” and “Tax Code Areas.”

• Taxing districts are individual governmental units with property tax authority, such as a county, city, fire

protection district, or library district. Governmental units without property tax authority (such as public

transportation benefit areas) are not considered taxing districts for these purposes.

• Tax Code Areas, or TCAs, are unique combinations of overlapping taxing districts.

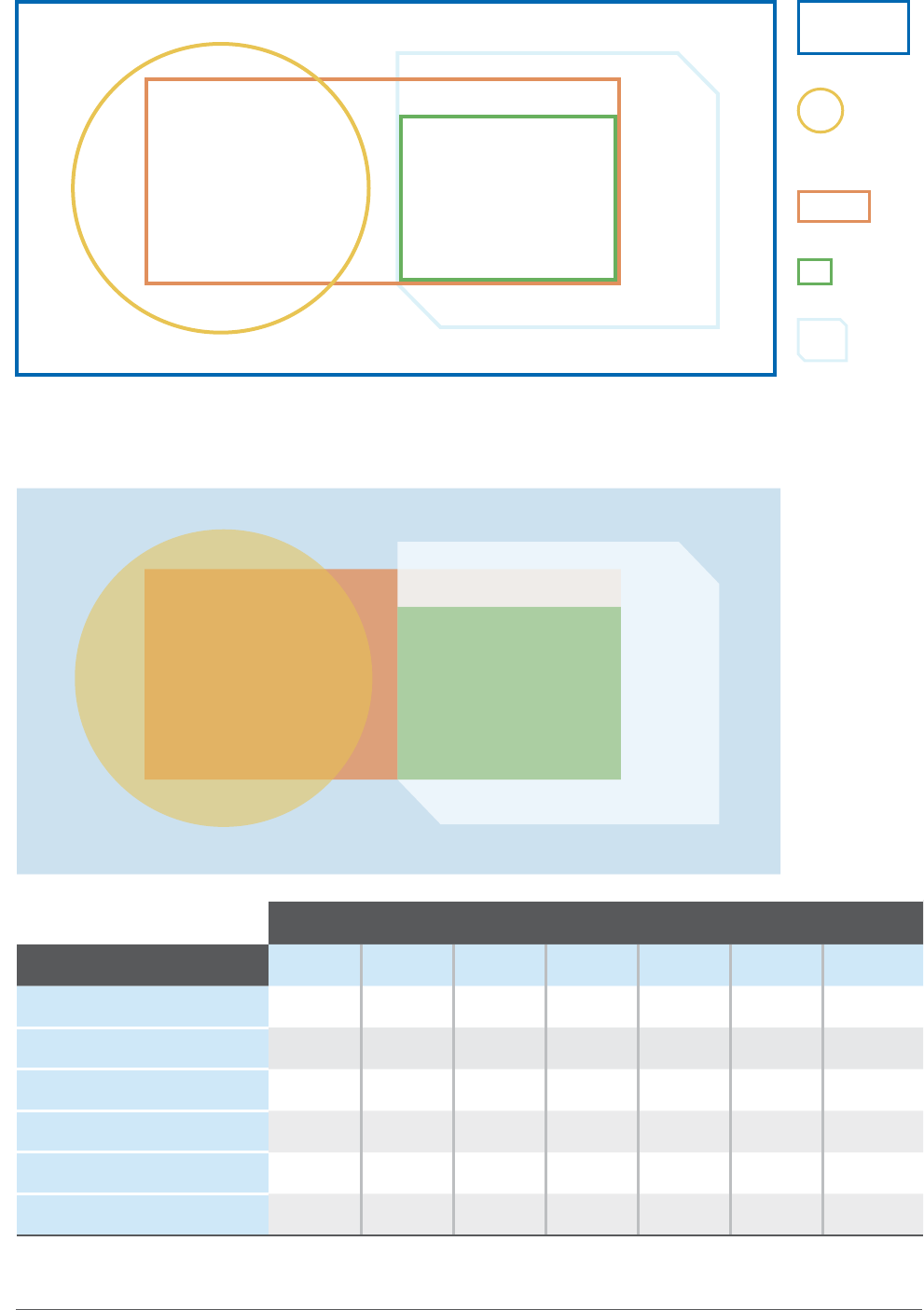

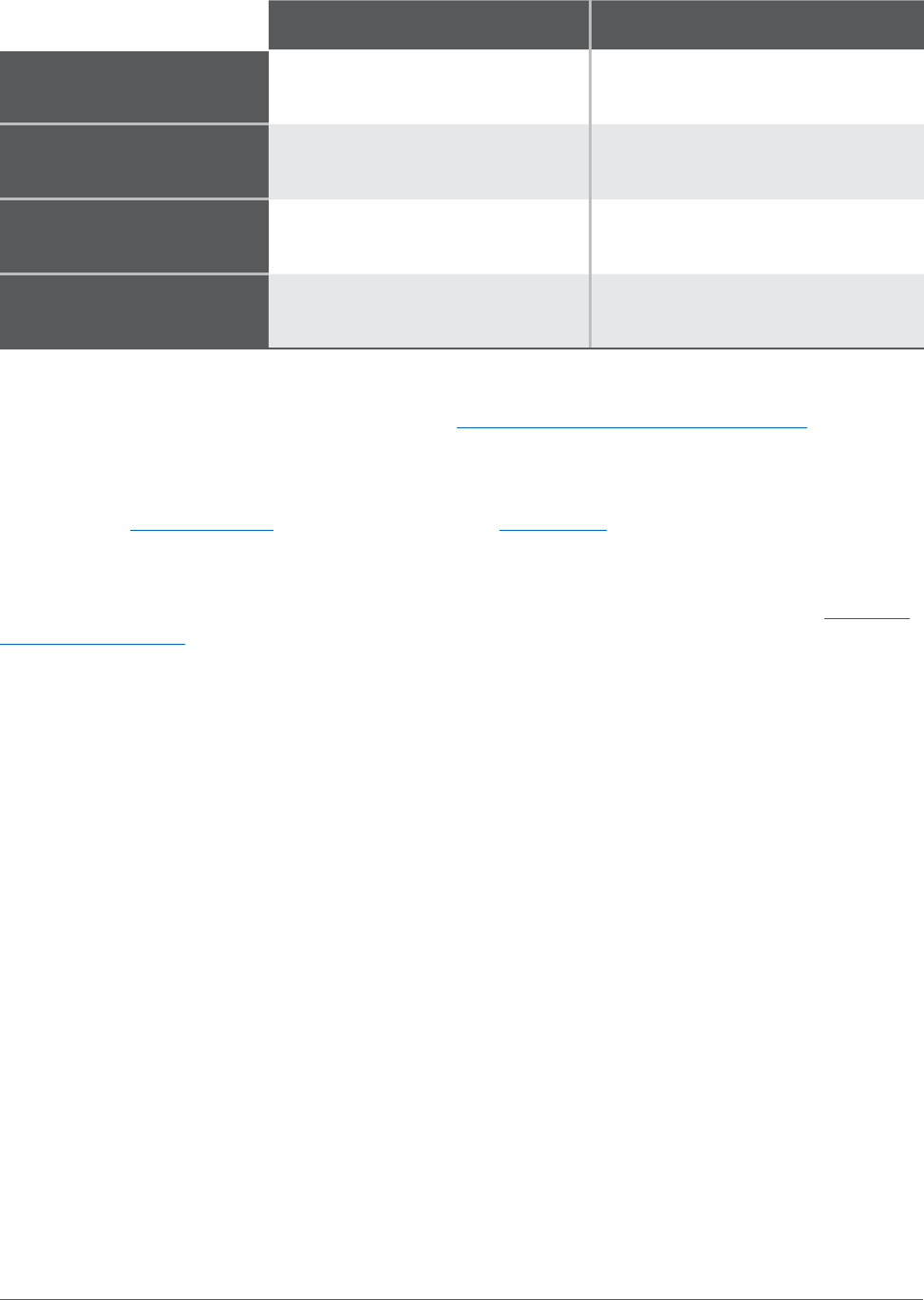

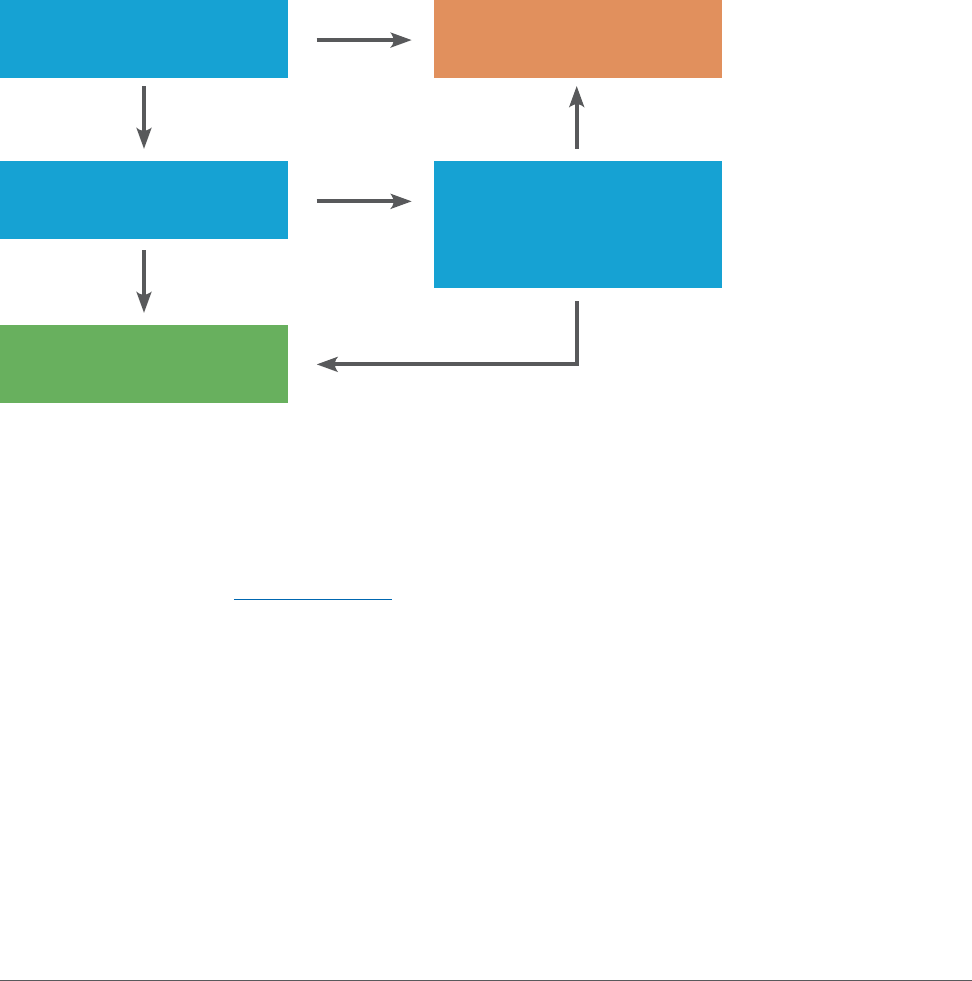

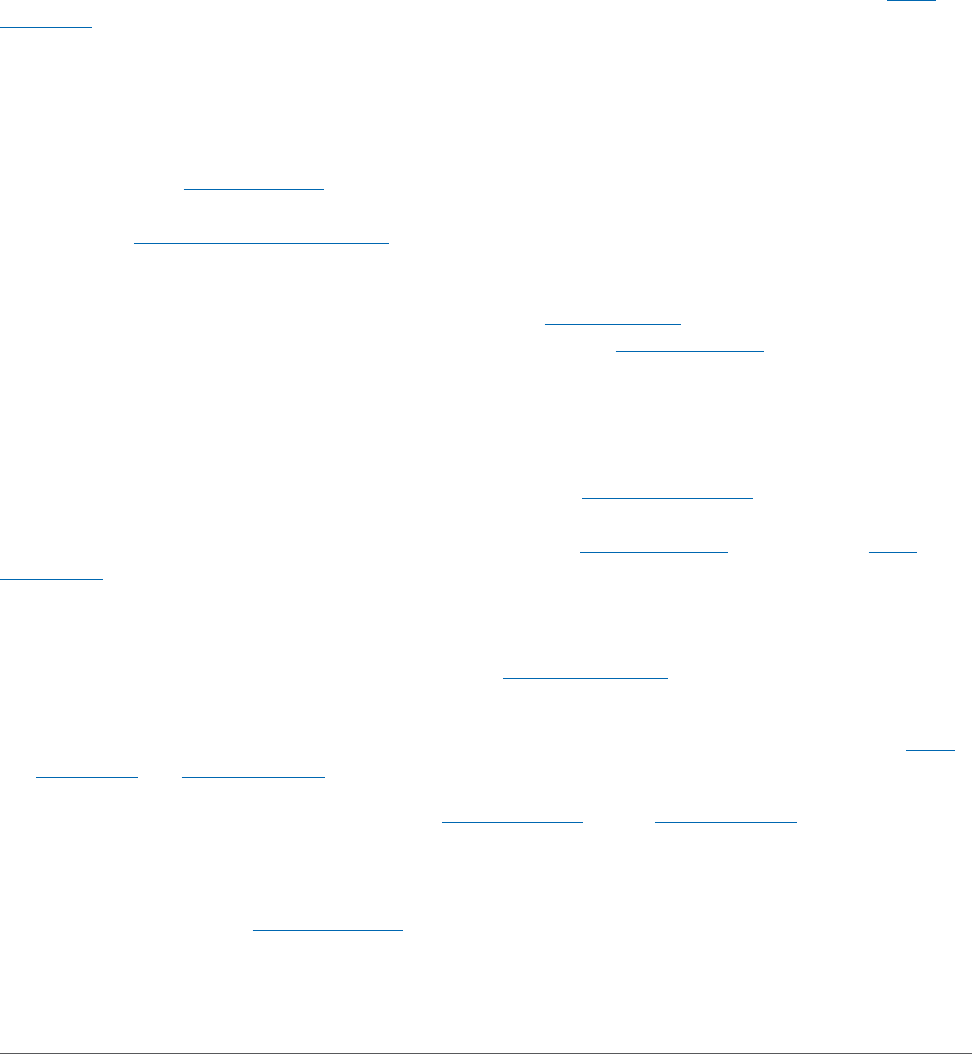

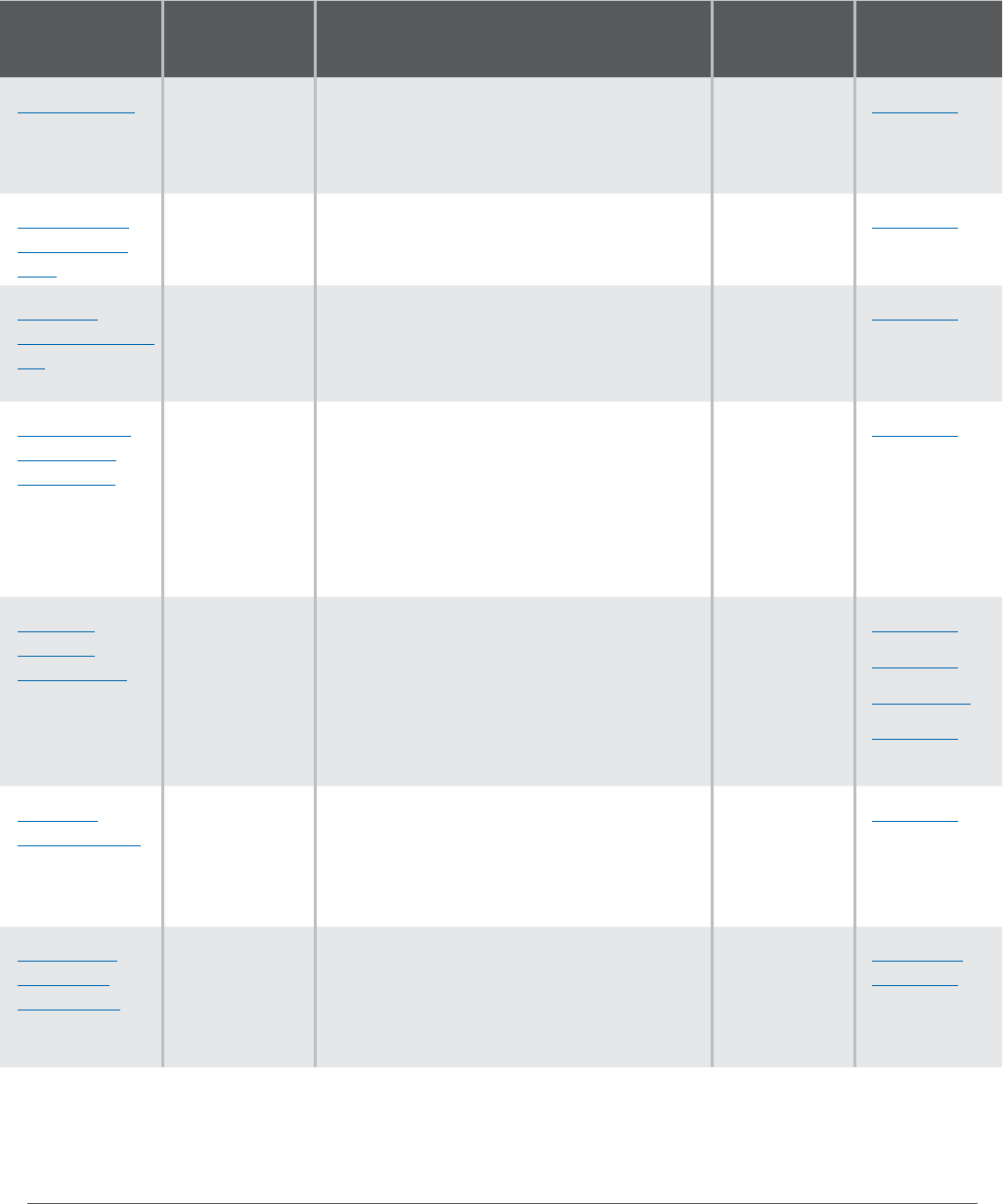

To demonstrate how multiple taxing districts overlap to form unique Tax Code Areas, see the example on the

next page. This example shows a hypothetical county with a city and several taxing districts (fire, library, and

public hospital). The districts overlap to form seven dierent Tax Code Areas, no two of which are the same.

(Note that the county itself is actually two separate taxing districts – one for the current expense levy, which is

imposed countywide, and one for the road levy, which is only imposed within unincorporated areas.)

Of course, in reality the picture is often much more complicated, as there are many additional taxing districts

that may be involved such as school districts, park districts, cemetery districts, port districts, public utility

districts, EMS districts, and more. But the same general principles will still apply.

According to the state Department of Revenue, there are approximately 3,200 unique Tax Code Areas

throughout the state as of 2021. The number of TCAs within each county depends on the number of taxing

districts within that county, as well as how they overlap geographically, since each district may have dierent

service boundaries.

Table of Contents

13

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

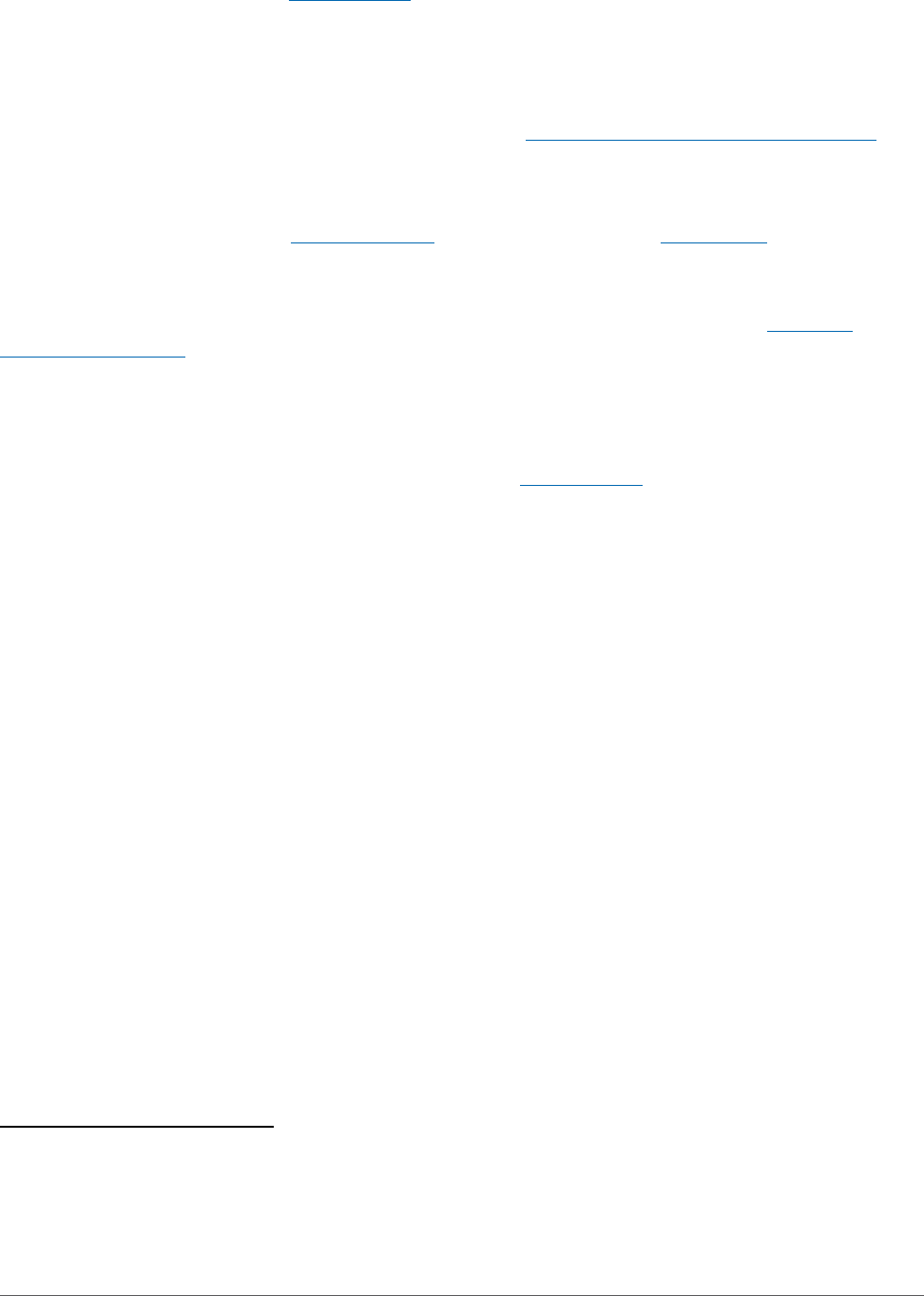

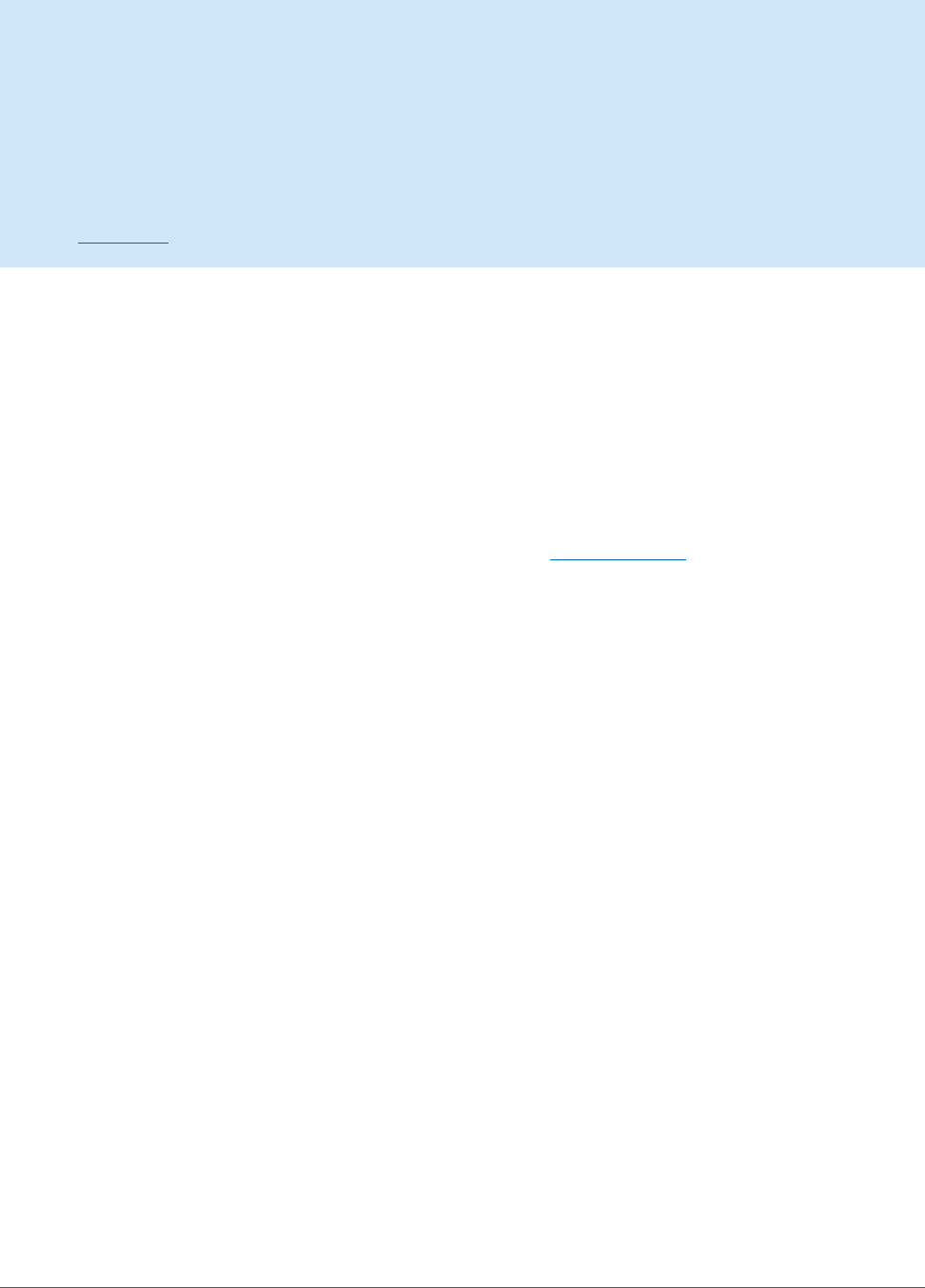

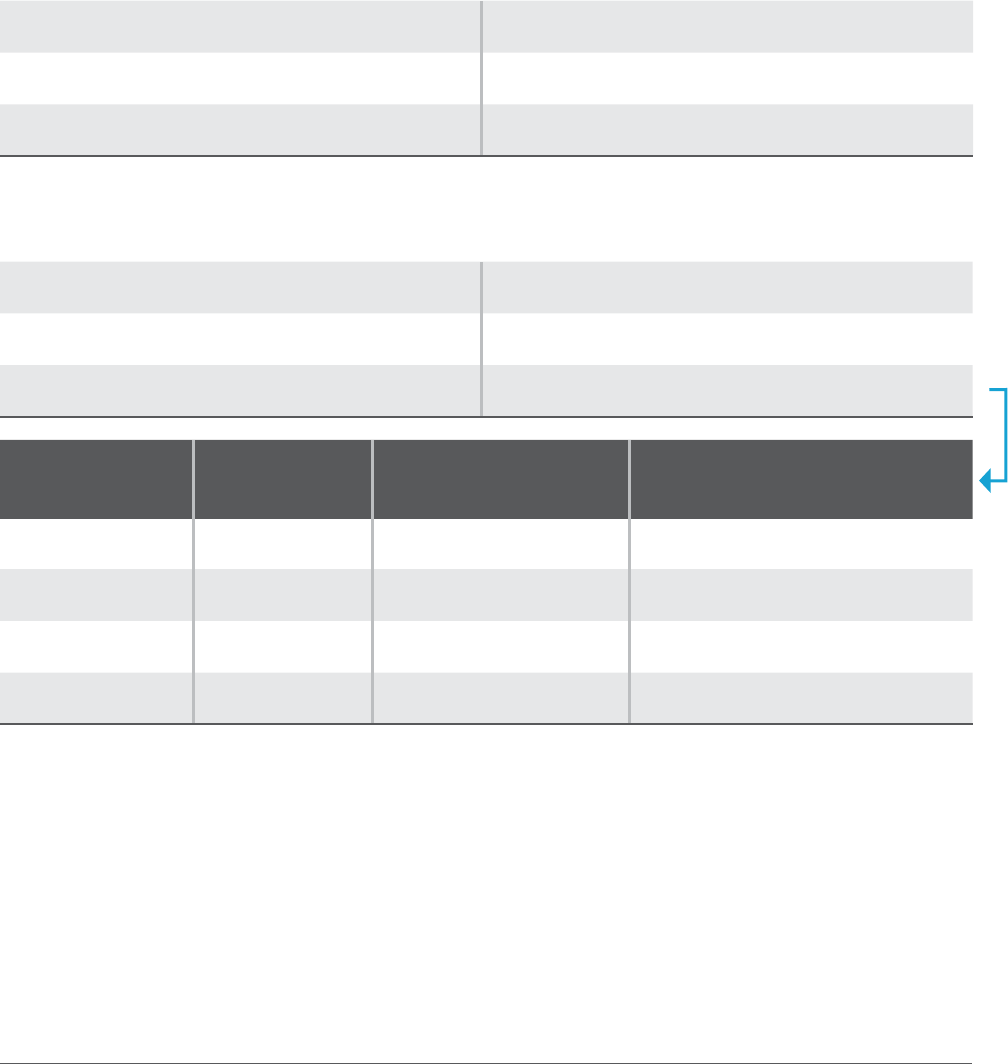

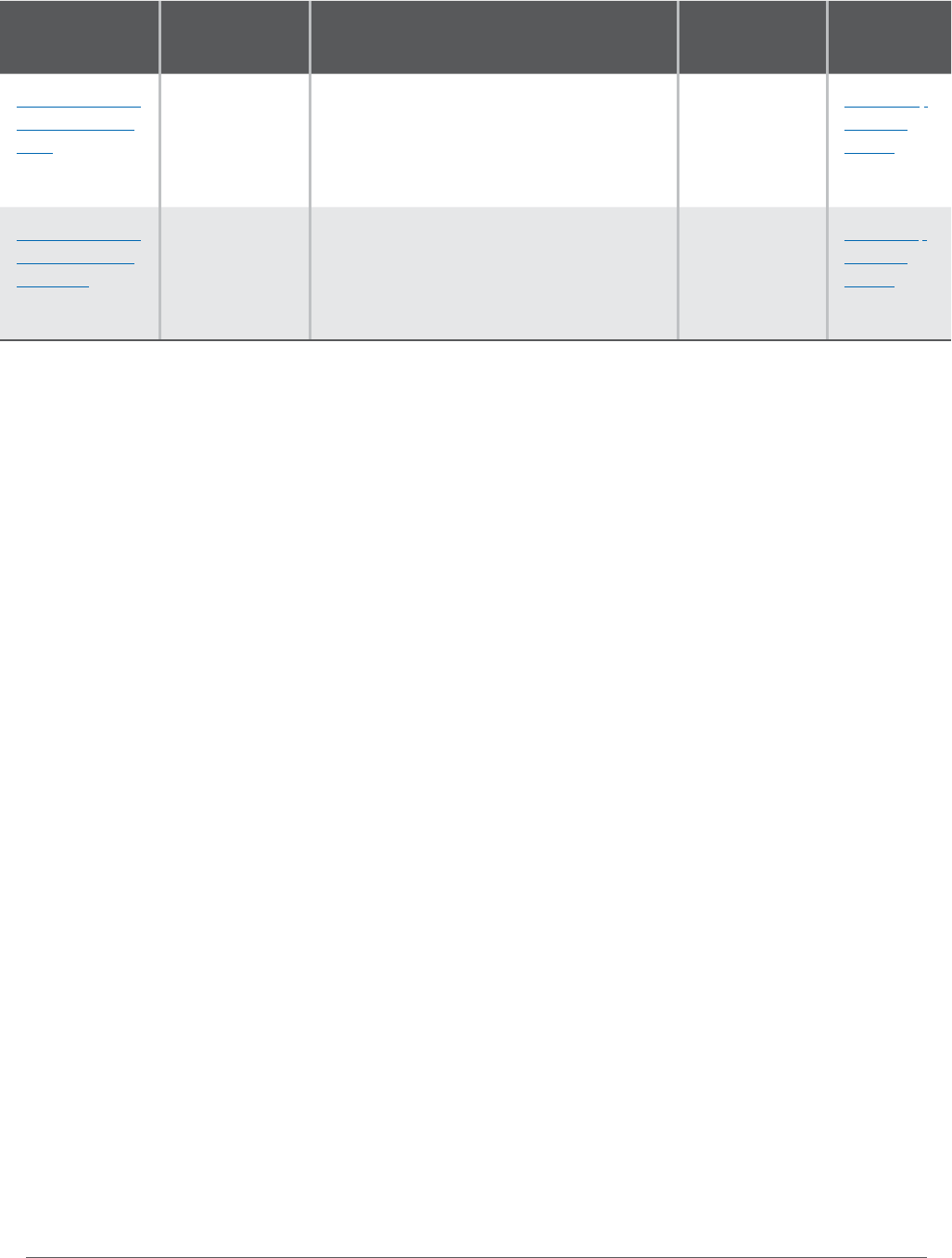

Taxing Districts Example

County*

Public Hospital

District

Fire District

City

Library District

A

B

C

D

E

A B C D E

*County current expense levy is countywide, but county road levy is only in unincorporated areas

Tax Code Areas

Belongs to Tax Code Area(s)

Taxing District 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

County Current Expense X X X X X X X

County Road X X X X X X

City X

Fire District X X X X

Public Hospital District X X

Library District

X X X

1 2 3 4 6

5

7

Table of Contents

14

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Since Washington uses a budget-based property tax system (see What is a Budget-Based Property Tax?), each

taxing district establishes its desired levy amount for the upcoming year during the budget process. The levy

rate for that taxing district is then calculated based on the assessed valuation within that taxing district.

Once the levy rate has been determined for each taxing district, the levy rates are added together within each

TCA. This provides a total (aggregate) levy rate that each property owner within the TCA must pay.

As noted earlier, the levy rate per $1,000 AV for any individual taxing district (city, county, etc.) must be uniform

throughout the district, meaning each property owner pays the same rate. Similarly, the aggregate (total

combined) levy rate within each Tax Code Area also must be uniform.

7

However, dierent properties within a single city may belong to dierent Tax Code Areas, and the aggregate

levy rate may vary considerably between TCAs. For instance, Bothell lies partially within King County and partially

within Snohomish County. The city’s levy rate must be the same for every property within the city, regardless of

which county the property is located in. However, the counties will almost certainly have dierent property tax

rates, which means the taxpayers within the King County portion of the city will pay a dierent aggregate levy

rate than those taxpayers in the Snohomish County portion of the city.

State law and the state constitution have established two limitations on the maximum aggregate levy rate

within any individual Tax Code Area: the $10 constitutional limit (which includes both the state and local

governments) and the $5.90 local government limit (which applies to most, but not all, local government levies).

$10 Constitutional Limit

Article 7, section 2 of the Washington State Constitution (also codified at RCW 84.52.050) limits the total regular

property tax rate on any individual property (i.e., within any individual Tax Code Area) – including state, county,

city, and most local government property taxes – to 1% of the property’s true and fair value. Since the levy rate

is expressed as a dollar amount per $1,000 assessed value, and since 1% of a property’s value is equivalent to

$10.00 per $1,000 assessed value, this is often referred to as the $10 limit.

To limit the confusion between the aggregate levy rate limit and the 1% inflation increase allowed each year

(see The 1% Annual Levy Lid Limit (“101% Limit”)), we will refer to the constitutional levy rate limit as the $10 limit.

Almost every property tax levy in the state is subject to the $10 constitutional limit. However, the state

constitution establishes three important exceptions:

• Port districts and public utility districts are exempt from the $10 limit.

• Any taxing district may exceed the $10 limit with a voter-approved “excess levy” for maintenance and

operations purposes, which for cities and most other jurisdictions

8

may only be approved one year at a

time (see Excess Levies (Operations & Maintenance)).

• Any taxing district may exceed the $10 limit for the repayment of voter-approved general obligation debt,

until the debt is repaid (see G.O. Bond Excess Levies (Capital Purposes)).

7 This does not mean the tax bill is the same for all property owners, however. The levy rate is multiplied by the assessed

value for each individual property to determine the tax bill. Since dierent properties have dierent assessed values, each

property owner within the same Tax Code Area must pay the same levy rate but will owe a dierent amount of tax.

8 Fire districts and school district are the only local governments authorized to impose a multi-year excess levy. All other

taxing districts, including counties, cities, and towns, may only impose one-year excess levies.

Table of Contents

15

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Everything under the $10 limit is generally referred to as a “regular” levy. Any levies above the $10 limit, which

require voter approval, are generally referred to as “excess” levies. The term “special” may be used to describe

any regular or excess levy that is levied for a specific purpose.

Of this $10, no more than $3.60 may be imposed by the state

9

(RCW 84.52.065) and no more than $5.90 may

be used by most local governments (see below). That adds up to a maximum of $9.50, which leaves at least

$0.50 extra that may be used for certain local government levies outside the $5.90 limit.

10

$5.90 Local Limit

By statute, the aggregate (total) regular levy rate for most local governments combined – including “senior

taxing districts” such as cities and counties, as well as “junior taxing districts” such as fire districts and park

districts – may not exceed $5.90 per $1,000 assessed valuation within any individual Tax Code Area (RCW

84.52.043). This $5.90 limitation is a subset of the $10 constitutional limit – in other words, all levies that are

subject to the $5.90 statutory limit are also subject to the $10 constitutional limit.

However, this statute also provides several exemptions. The following local levies are subject to the $10

constitutional limit but are not subject to the $5.90 local limit:

• Aordable housing levies

• County conservation futures levies

• County criminal justice levies

• County ferry district levies

• Emergency medical services (EMS) levies

• Up to $0.25 of a fire district or regional fire authority levy, if protected from prorationing by the legislative body

• Regional transit authority levies (Sound Transit)

There are also a few other, narrower exemptions, including certain flood control zone levies, a portion of

metropolitan park district levies for metropolitan park districts with a population of 150,000 or more (with voter

approval), and King County’s transit levy.

There are four types of local government levies that are not subject to either the $5.90 or $10 limits:

• General obligation (G.O.) bond excess levies

• Excess maintenance & operation levies

• Port district levies

• Public utility district levies

9 In 2017 and 2018, the state Legislature temporarily adjusted the state levy rate to provide additional funding for the

state’s share of K-12 education. The maximum levy rate in 2019 is $2.40/$1,000 AV and in 2020 and 2021 is $2.70/$1,000 AV.

In 2022, the maximum rate returns to $3.60/$1,000 AV.

10 In reality, there will be more than $0.50 available if the state is levying less than its maximum $3.60 and/or the local

districts are levying less than the maximum $5.90.

Table of Contents

16

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

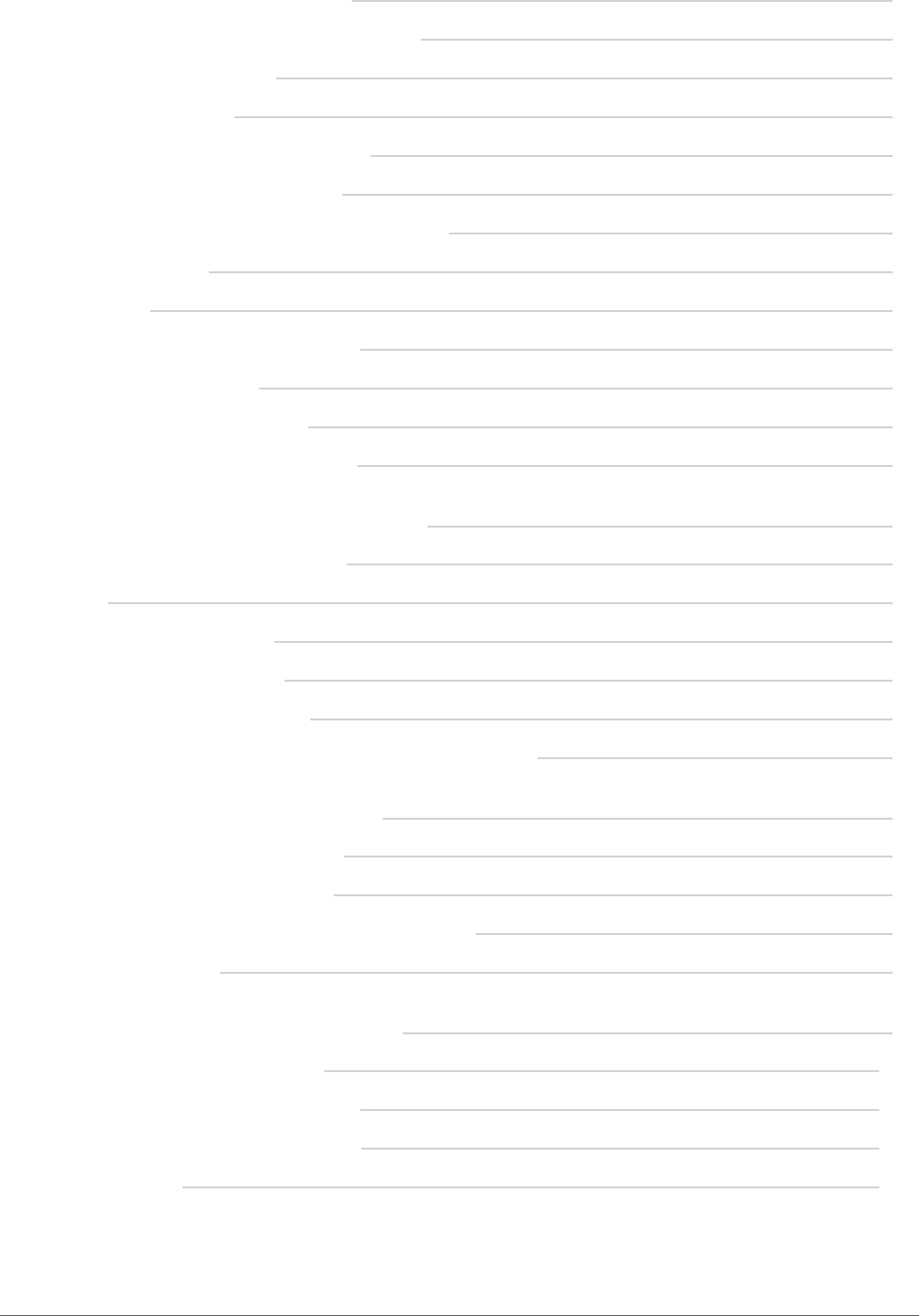

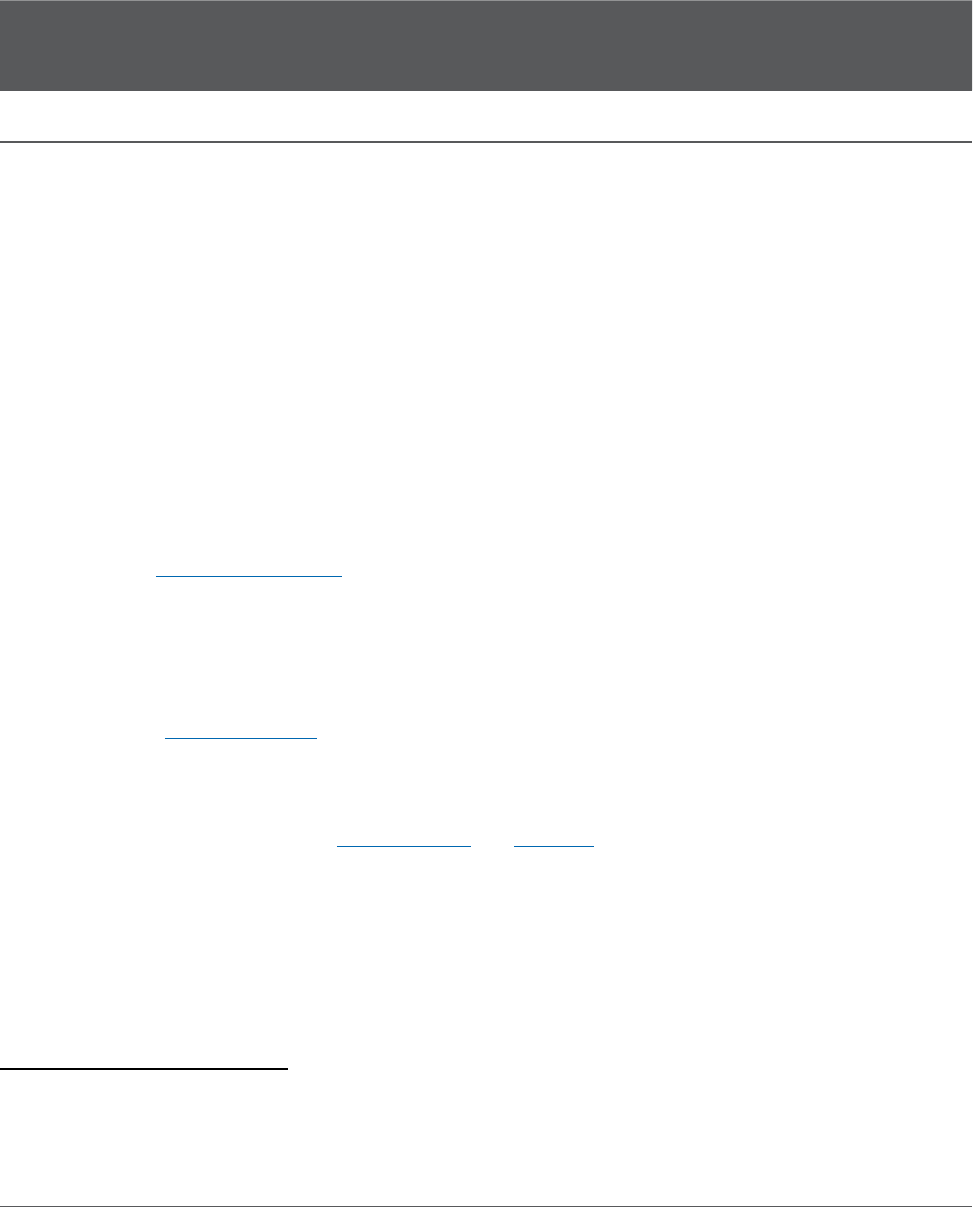

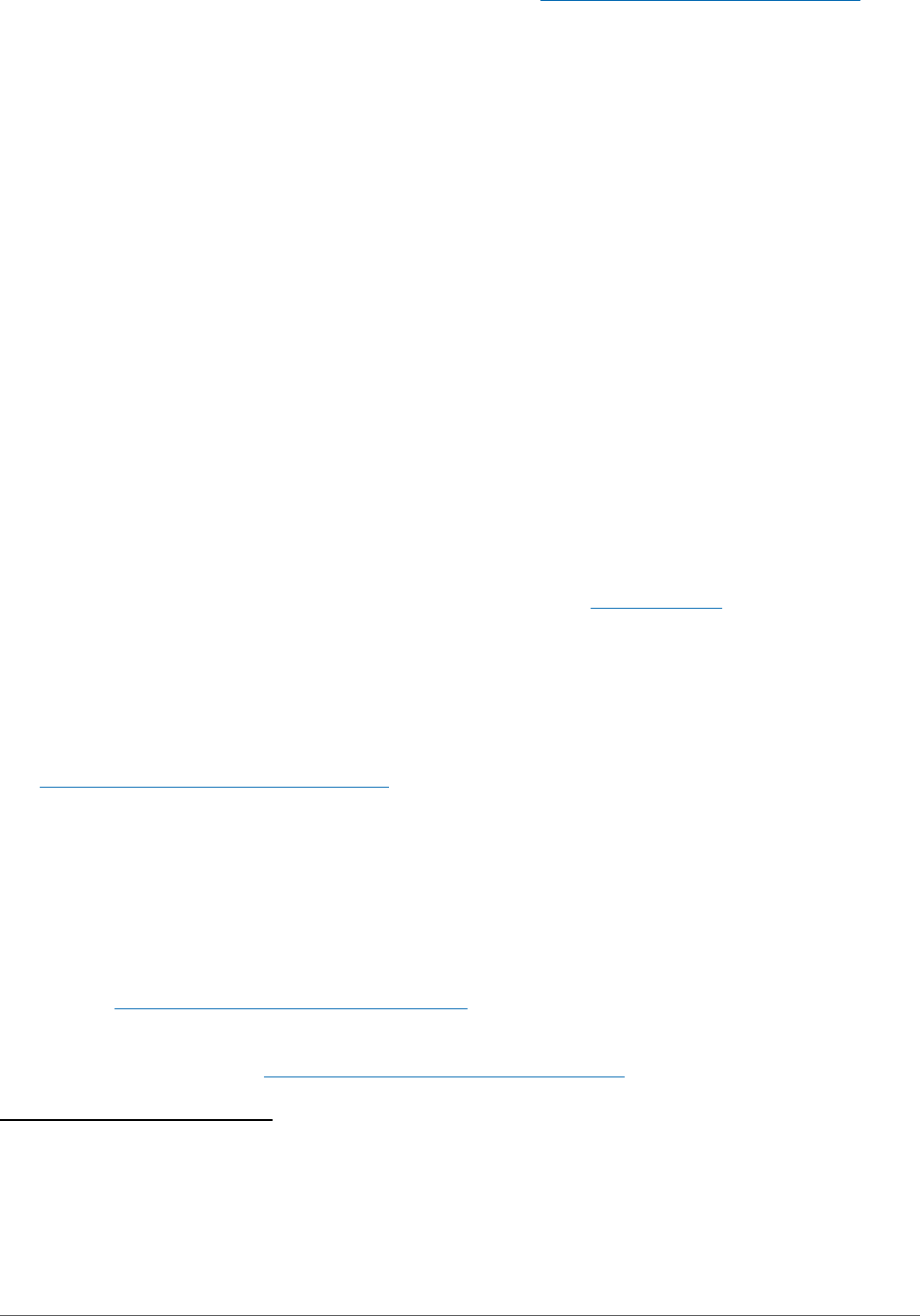

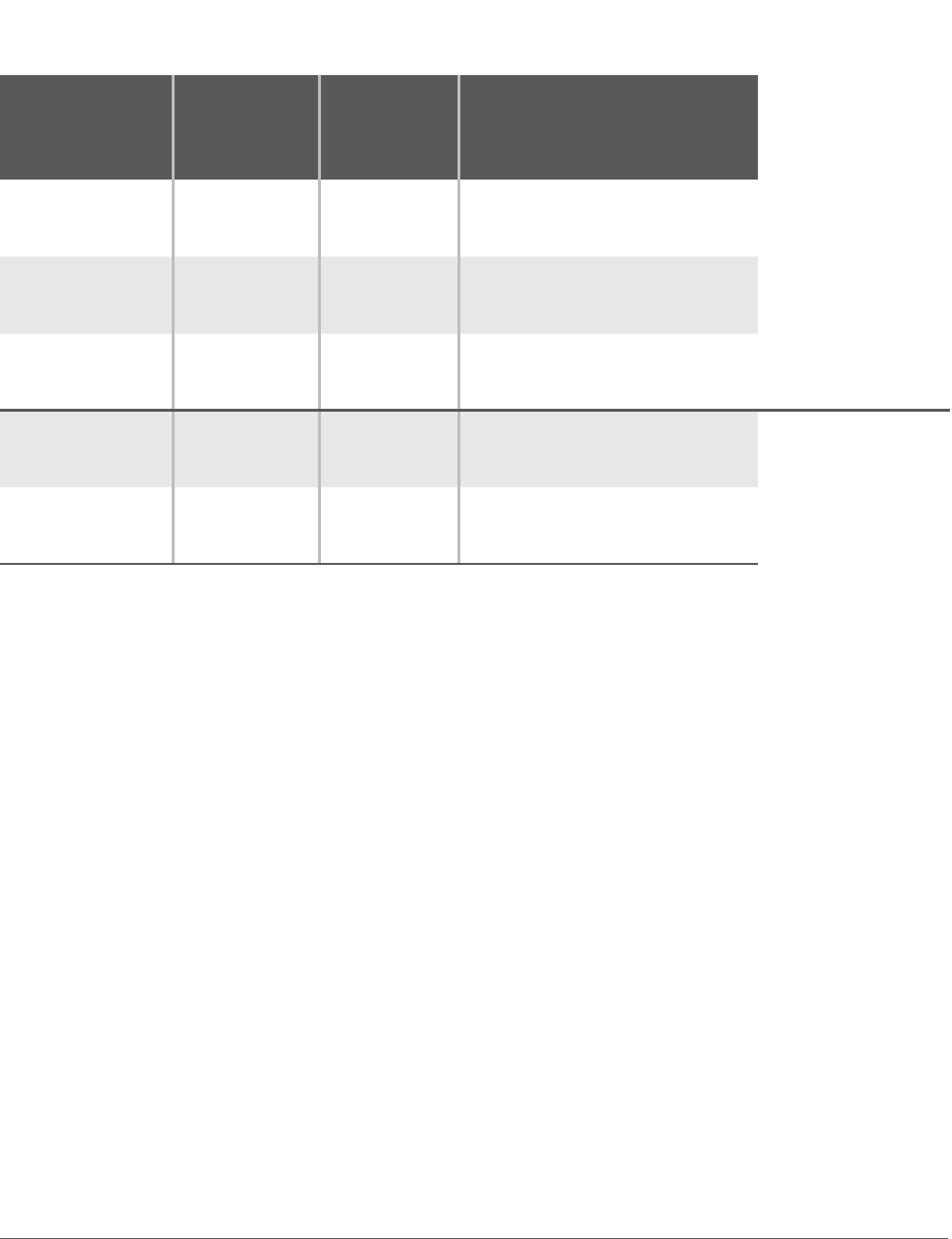

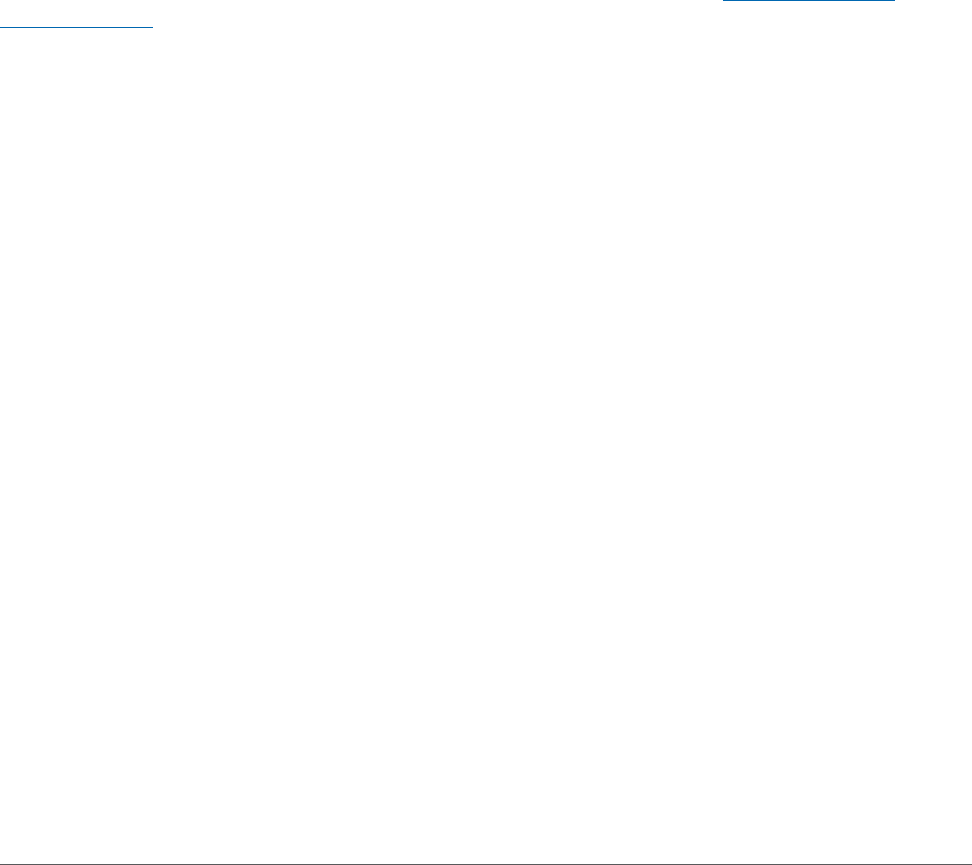

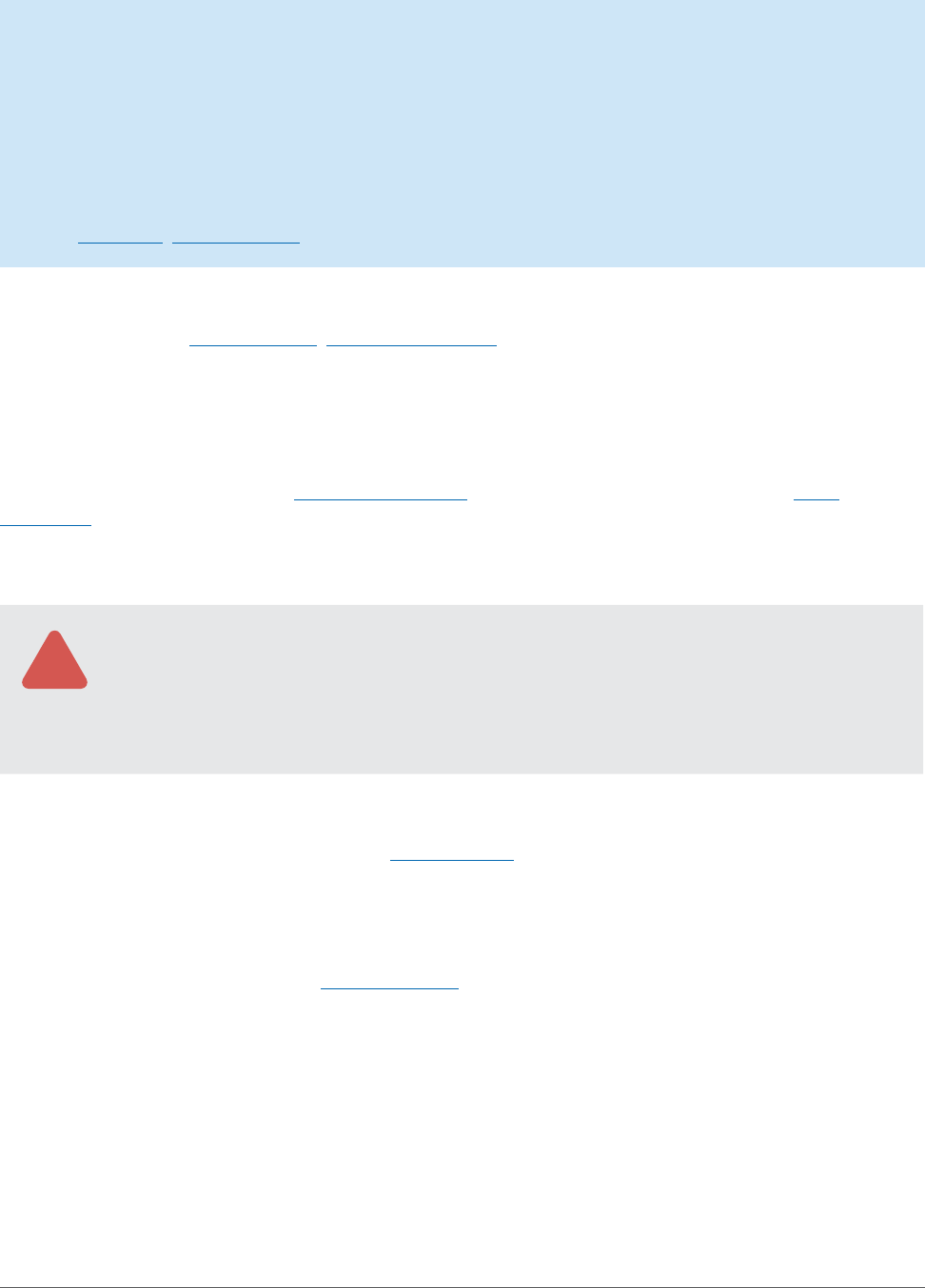

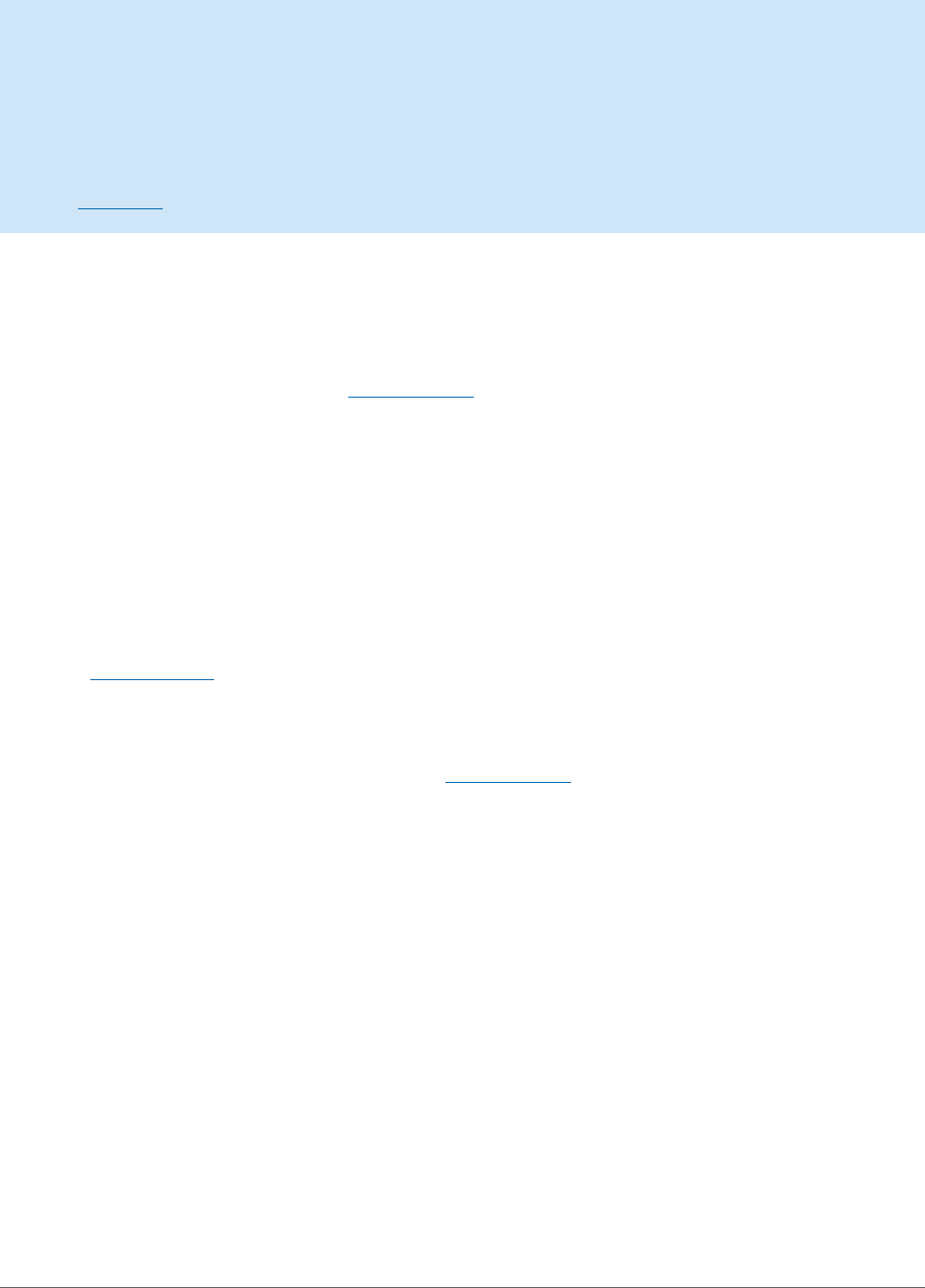

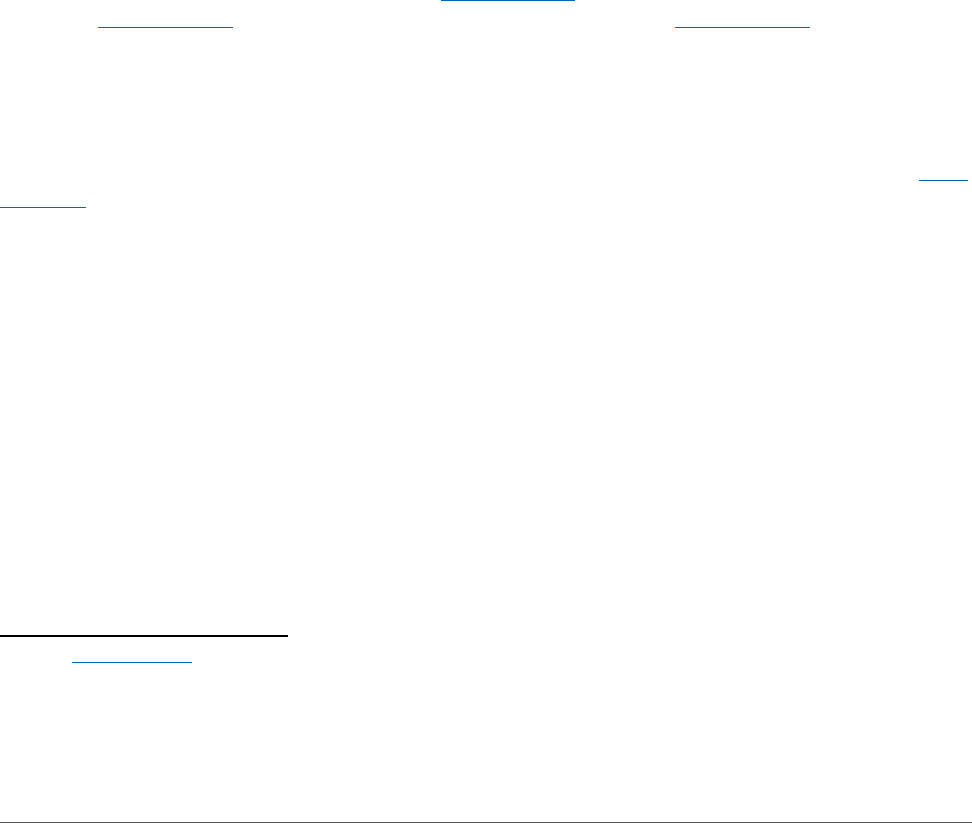

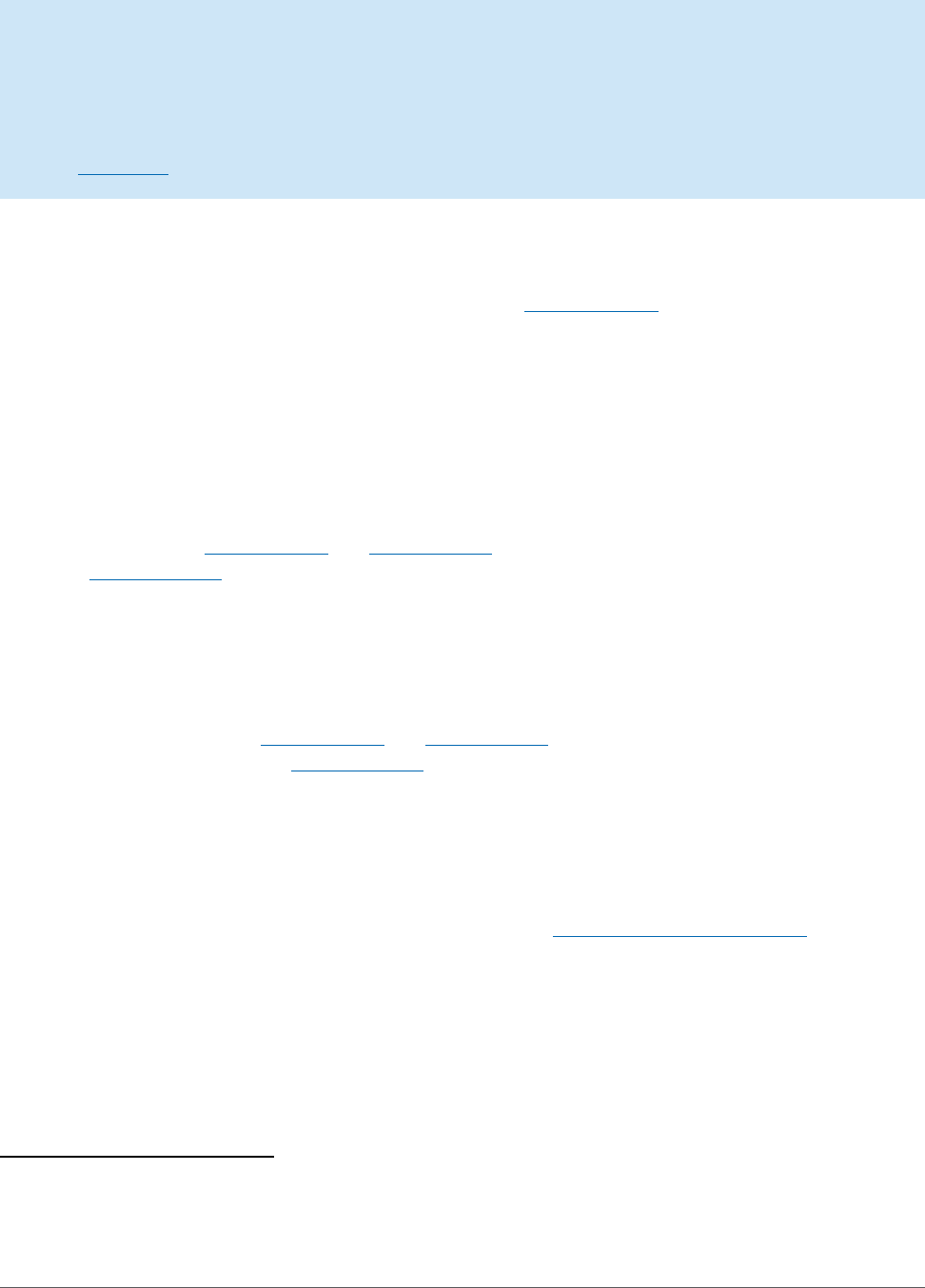

The chart below demonstrates both the $10 constitutional and $5.90 local government limits.

Levies above $10 limit:

• Excess levies (annual O&M or for repayment of U.T.G.O. bonds)

• Port and PUD levies

Remaining levy capacity available for:

• EMS levies

• Aordable housing levies

• County criminal justice, conservation futures, ferry, and transit levies

• Regional transit authority levies

• Protected portions of metropolitan park district, fire district, regional fire

authority, and flood control zone district levies

$5.90 limit–includes:

• City regular levy

• County current expense and road levies

• Cultural access program levies

• Most metropolitan park district levies

• Most special purpose district levies except ports and PUDs

$10 Constitutional Limit

Other

At least

$0.50

Local Districts

Up to

$5.90

State

Up to

$3.60

Prorationing

Once each taxing district establishes its desired levy amount for the upcoming year, no later than November

30 for cities, the county assessor calculates the levy rate for each taxing jurisdiction based on the assessed

valuation within that jurisdiction. The county assessor then adds up the levy rates for each Tax Code Area.

If either the $10 constitutional limit or the $5.90 statutory limit is exceeded within any individual Tax Code Area,

the county assessor must reduce the local levies to $10 or $5.90 according to the statutory formula found in

RCW 84.52.010, a process known as “prorationing.” Prorationing essentially establishes a levy hierarchy, and

levies on the lowest rungs of the ladder are reduced or eliminated until the $10 or $5.90 limit is no longer

exceeded. The formulas for prorationing depend on which limit – $10 or $5.90 – was exceeded. (Remember

that certain levies are exempt from the $5.90 or $10 limitations and are not counted for those purposes.)

First, the county assessor must check to make sure that the $5.90 local limit has not been exceeded within any

Tax Code Area. If the $5.90 limit has been exceeded, the assessor must reduce the aected levies to a total

combined rate of $5.90.

After the assessor has checked the $5.90 limit and, if necessary, conducted any prorationing, the assessor

must then make sure the $10 constitutional limit has not been exceeded. If the $10 limit has been exceeded

within any Tax Code Area, the assessor must reduce the aected levies to a total combined rate of $10.

The prorationing order for both the $5.90 and $10 limits is shown on the next page. In general, the city general

fund levy is protected from prorationing. However, some other city levies may be subject to prorationing.

Since the levy rate within each taxing district must be uniform, any taxing district aected by prorationing must

reduce its levy throughout the entire district, and not just within the aected Tax Code Area.

For a more detailed discussion of prorationing, including examples, refer to the DOR Levy Manual.

Table of Contents

17

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

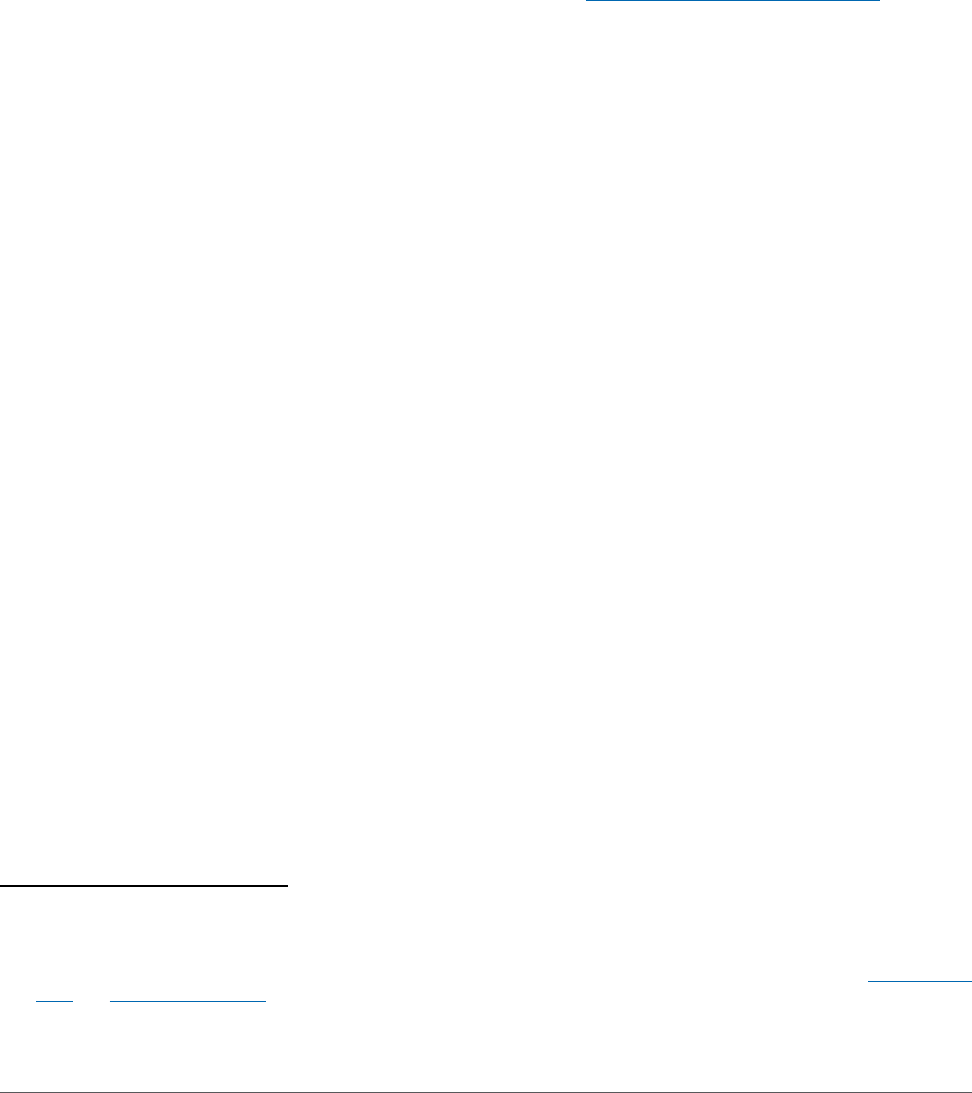

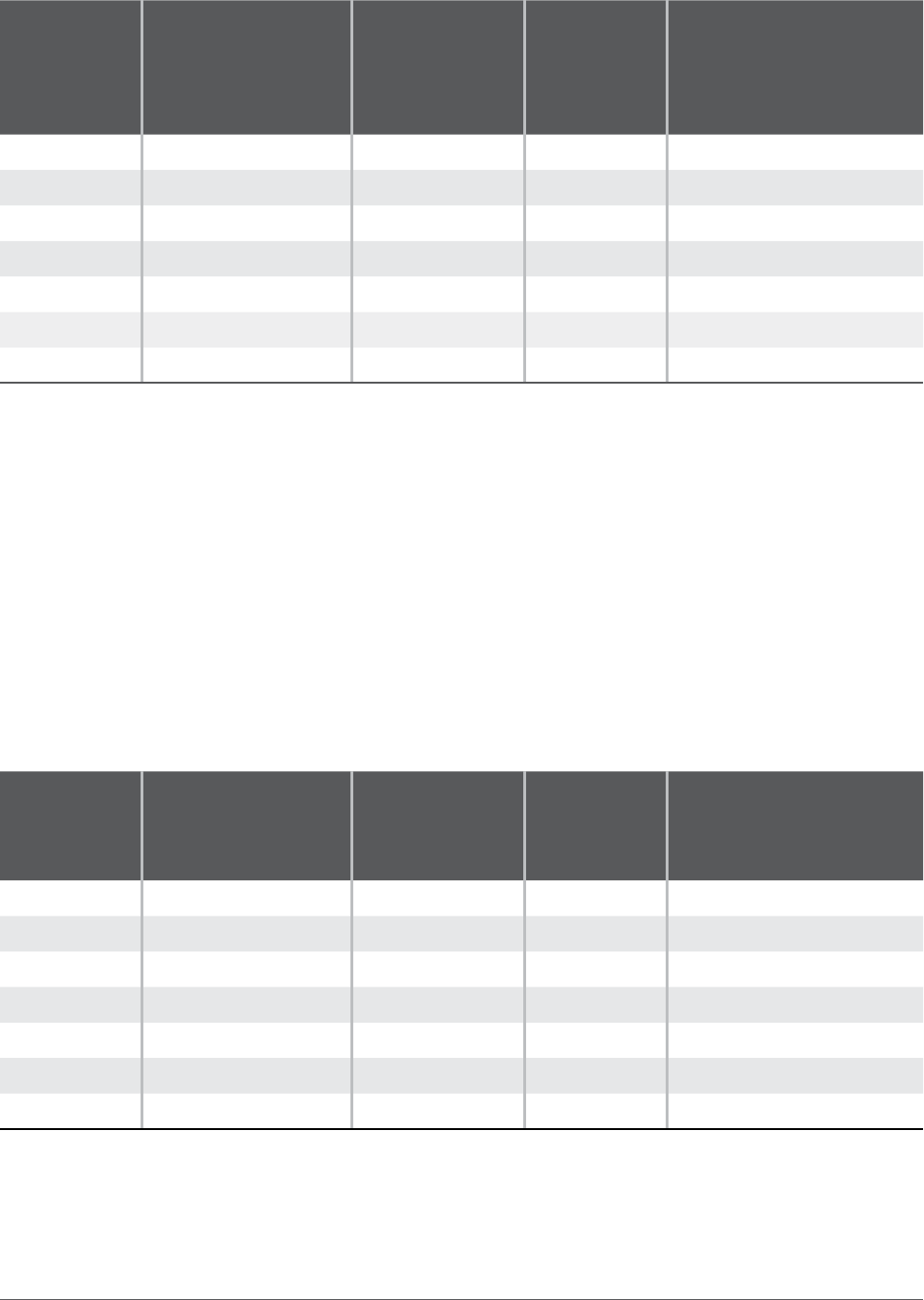

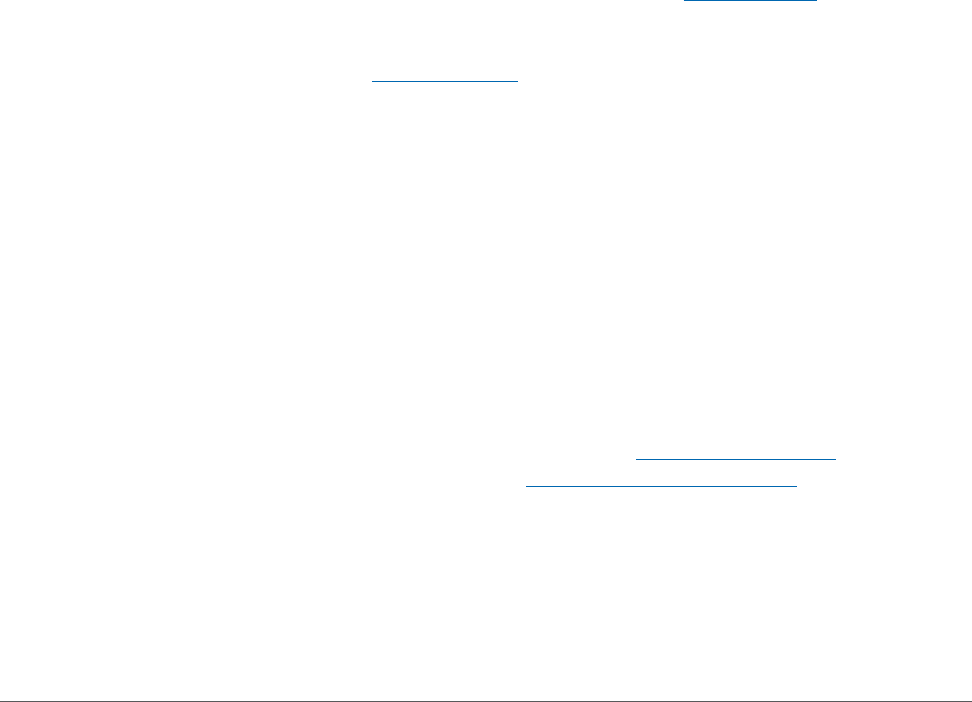

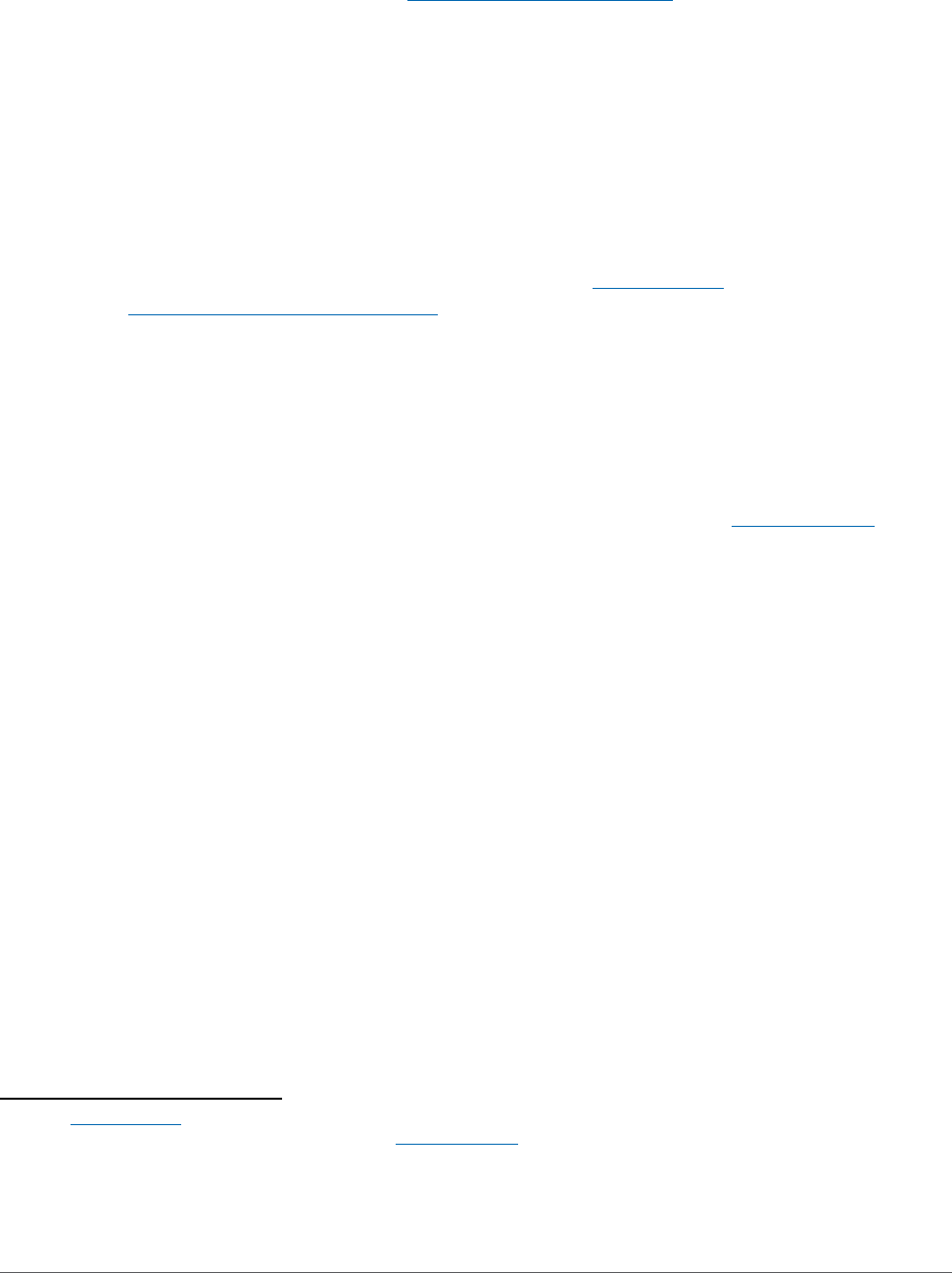

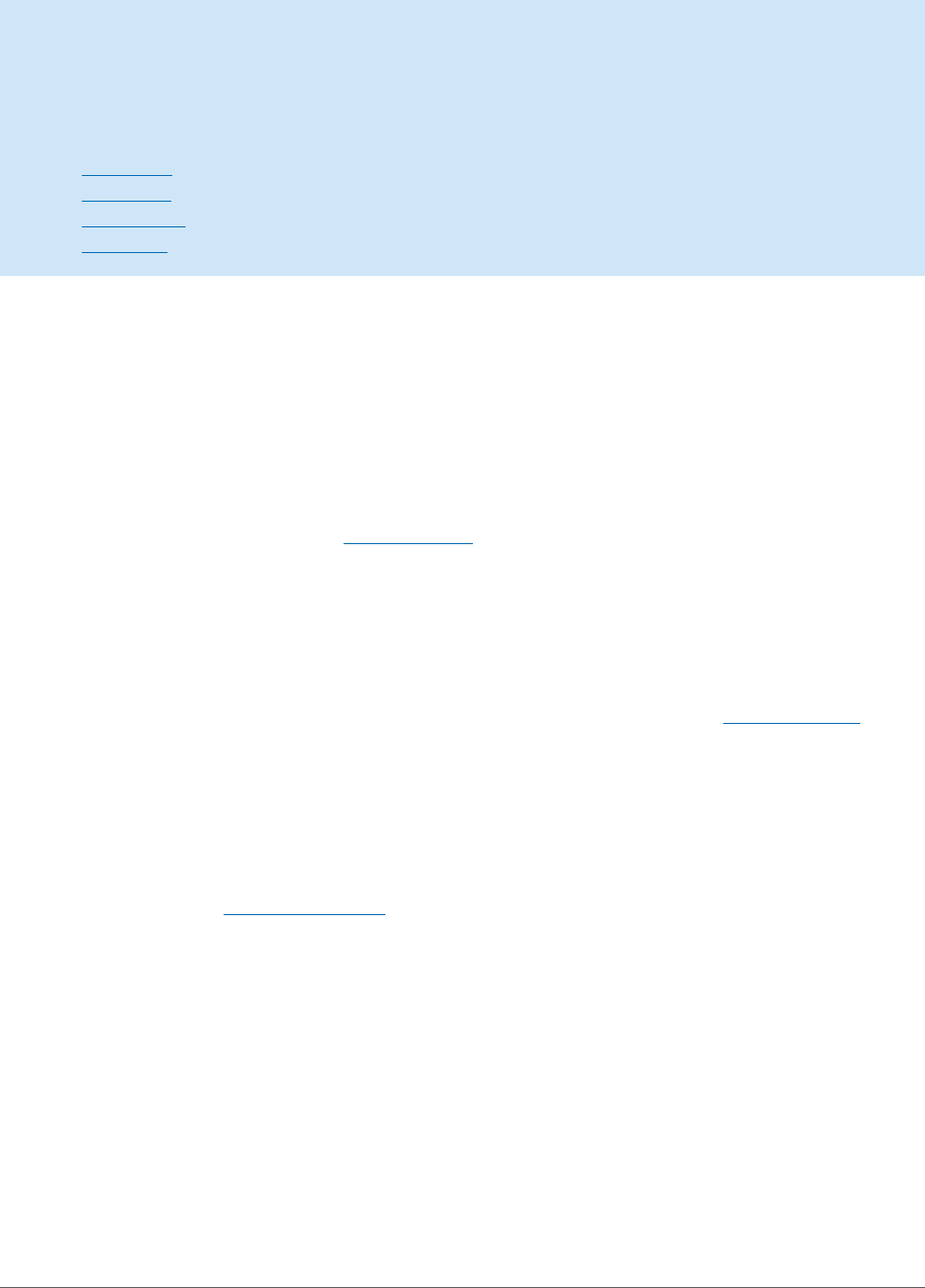

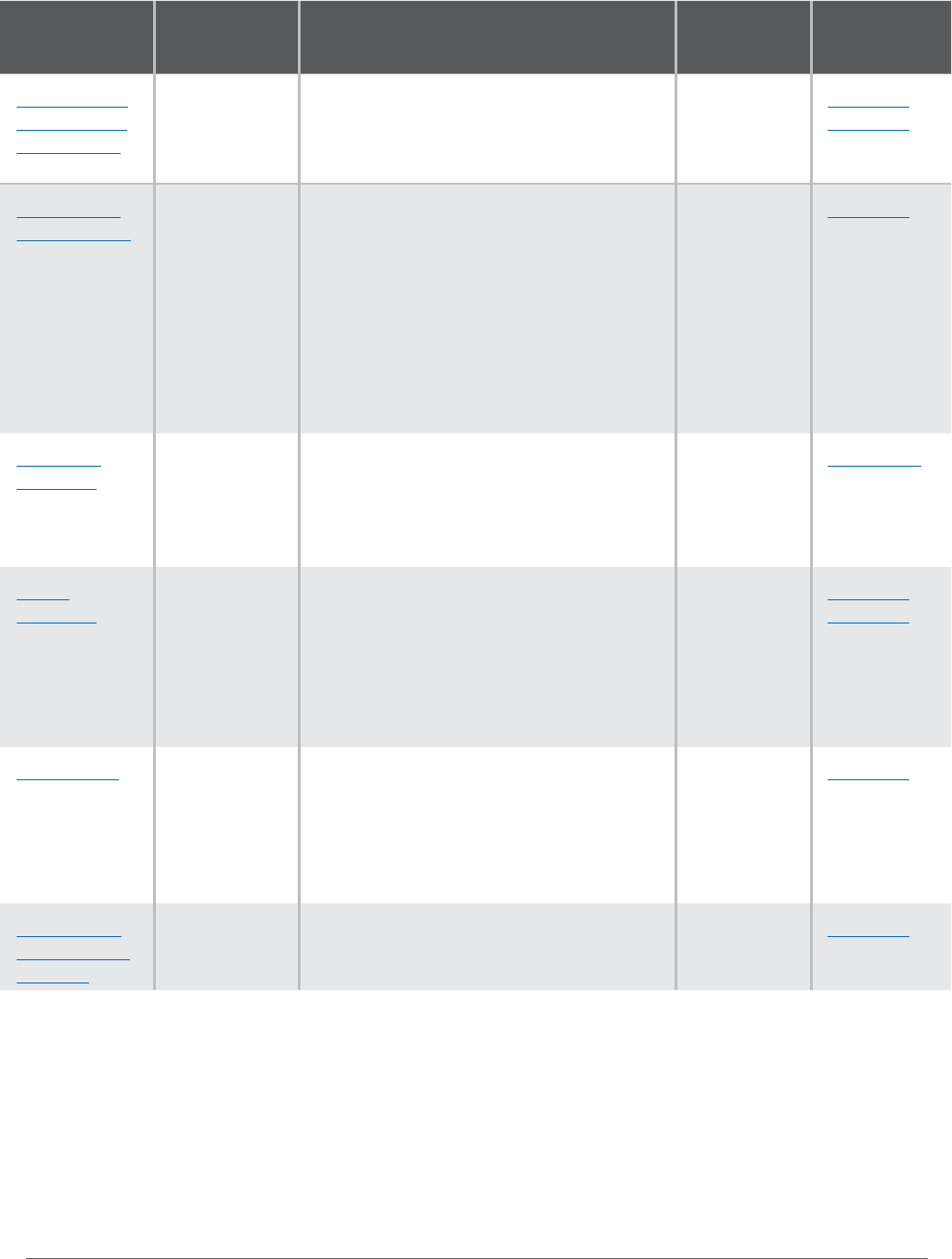

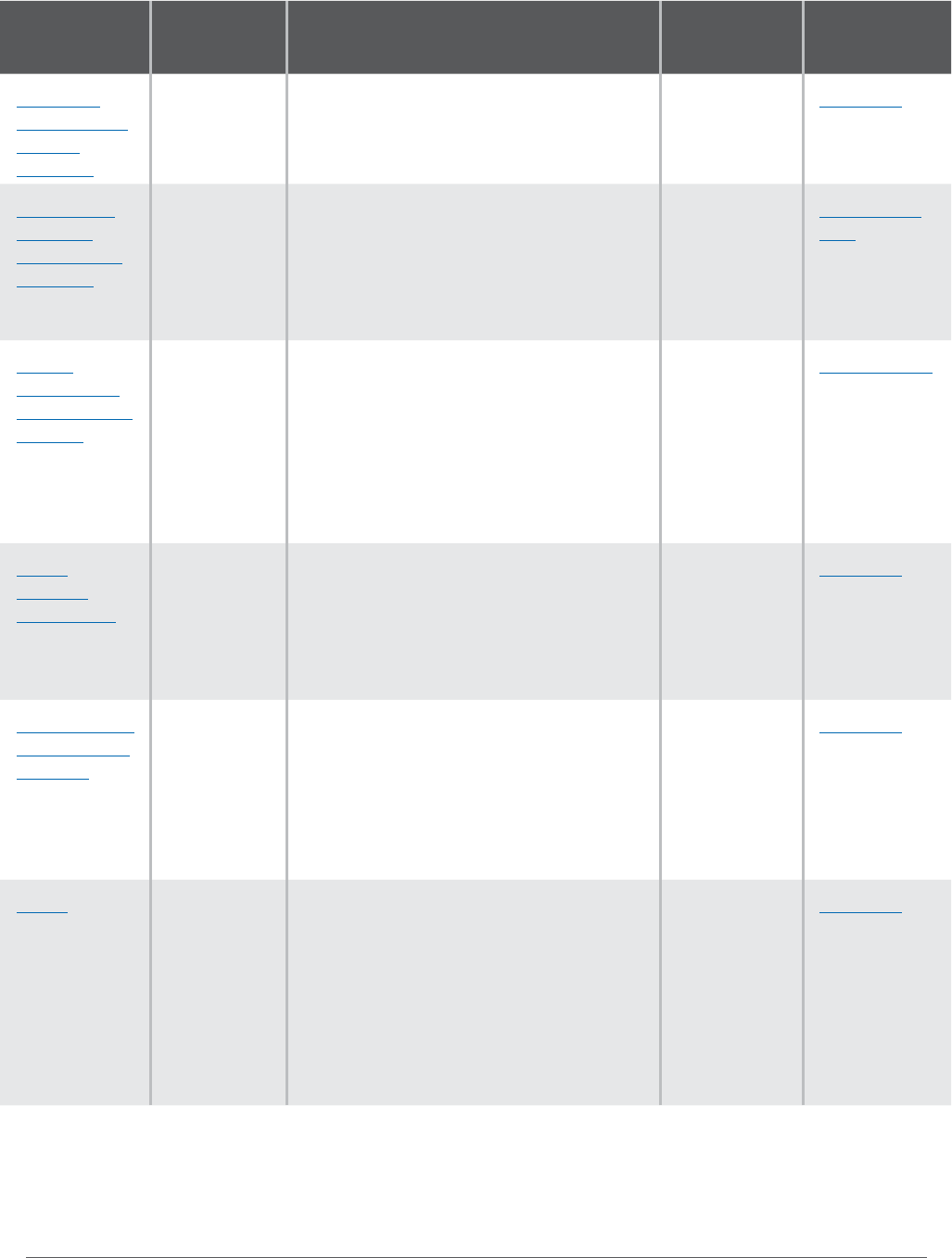

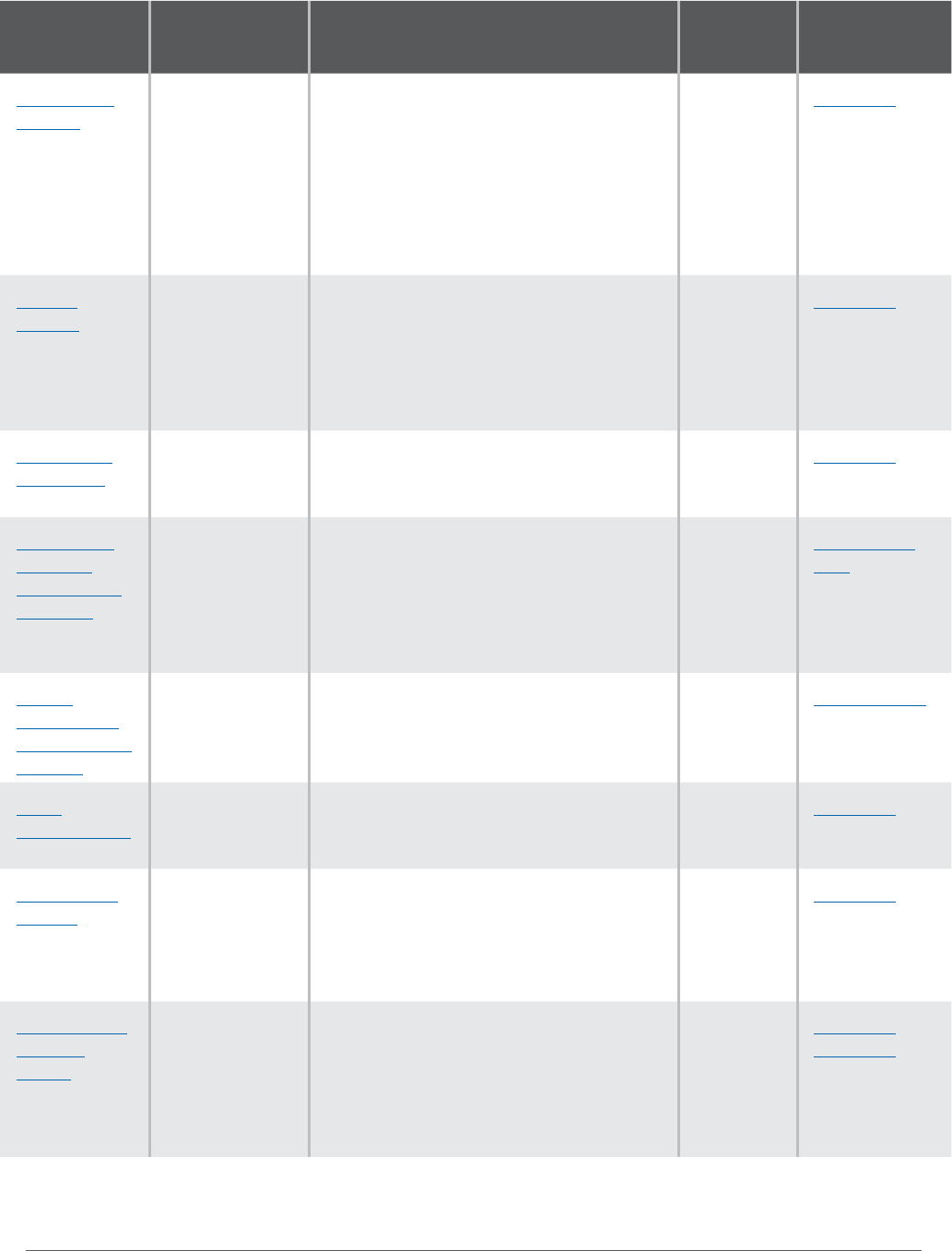

Property Tax Prorationing Order (RCW 84.52.010)

$5.90 reductions take place first, followed by $10 reductions

Levy Type

$5.90

Reduction

Order

$10

Reduction

Order

(a) County road levy shift*

(b) City fire pension levy* – only if city is annexed to fire/library district

st st

Flood control zone district – up to $0.25 if protected under RCW 84.52.816

—

nd

King County transit levy

—

rd

(a) Fire protection district – up to $0.25 if protected under RCW 84.52.125

(b) Regional fire authority – up to $0.25 if protected under RCW 84.52.125

—

th

County criminal justice

—

th

County ferry district — th

Metropolitan park district of 150,000+ population – up to $0.25 if protected

under RCW 84.52.120

—

th

(a) County land conservation futures

(b) Aordable housing

(c) EMS – first $0.20

—

th

EMS – remaining $0.30

—

th

Cultural access program nd th

(a) Park and recreation district

(b) Park and recreation service area

(c) Cultural arts, stadium, and convention district

(d) City transportation authority (monorail)

rd th

Flood control zone district – portion not protected under RCW 84.52.816 th th

(a) Public hospital district – first $0.25

(b) Metropolitan park district – first $0.25, if not protected under RCW 84.52.120

(c) Cemetery district

(d) All other junior taxing districts not otherwise mentioned in this chart

th th

Metropolitan park districts created in 2002 or later – remaining $0.50 th th

(a) Fire protection district – $1.00 under RCW 52.16.140/RCW 52.16.160, if not

protected under RCW 84.52.125

(b) Regional fire authority – $1.00 under RCW 52.26.140(1)(b) and (1)(c), if not

protected under RCW 84.52.125

th th

(a) Fire protection district – $0.50 under RCW 52.16.130

(b) Regional fire authority – $0.50 under RCW 52.26.140(1)(a)

(c) Library district

(d) Public hospital district – remaining $0.50

(e) Metropolitan park districts created in 2001 or earlier – remaining $0.50

th th

(a) County current expense levy

(b) City regular (general fund) levy

(c) County road levy

th

th

Regional transit authority

—

State school levies

—

th

(a) Port district

(b) Public utility district

(c) Excess levy

(d) G.O. bond levy

— —

* Not ocially considered “prorationing” under RCW 84.52.010. However, neither a road levy shift (see RCW 84.52.043) nor a city

firefighters’ pension fund levy (if the city is annexed to a library district, fire district, or regional fire authority – see RCW 41.16.060)

may cause any other taxing district to have its levy reduced. These levies must be reduced, eliminated, or “bought down” before

prorationing takes place.

Table of Contents

18

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

Buy-Down Agreements

If either the $5.90 or $10 limits are going to be exceeded, state law allows taxing districts to potentially

reduce the impacts of prorationing through the use of levy “buy-down” agreements (RCW 39.67.010 and

RCW 39.67.020). A buy-down agreement allows a taxing district to avoid prorationing by paying another

taxing district to reduce its levy so that the $5.90 or $10 levy limits are no longer exceeded.

If a city levy is in danger of being reduced or eliminated through prorationing, the city can potentially buy down

the levy rate of a smaller taxing district (such as a park district or cemetery district) within the aected Tax Code

Area. We suggest buying down the levy rate of the jurisdiction with the lowest assessed valuation, which will

minimize the city’s buy-down costs.

A levy buy-down also may be politically prudent in case a city levy increase, such as a levy lid lift, might cause

the levy of a junior taxing district to be reduced through prorationing.

If a buy-down agreement is signed, the city must notify the governing bodies of every taxing district whose

property tax levy could be adversely impacted by the agreement.

For examples of buy-down agreements, visit MRSC’s Sample Document Library.

Table of Contents

19

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

REGULAR LEVY GENERAL FUND

Quick Summary

• Primary source of property tax revenues for cities – revenues are unrestricted and may generally be

used for any lawful governmental purpose.

• Maximum levy rate varies between $1.60 and $3.825 depending on whether city is annexed to a fire

district/library district, participates in a regional fire authority, and/or has a fire pension fund.

RCW: 84.52.043(1); other statutes may apply

The general fund levy – often referred to as simply the “regular” property tax levy – is the primary source of

property tax revenue for any city or town.

11

The maximum levy rate depends on whether the city is annexed

to a fire protection district or library district, participates in a regional fire authority (RFA), or has a pre-LEOFF

firefighter’s pension fund.

12

• If your city IS NOT annexed to a fire district or library district and does not participate in a regional fire

authority: Your maximum levy rate is $3.375 per $1,000 assessed value (RCW 84.52.043(1)).

• If your city IS annexed to a fire district or library district or participates in a regional fire authority: Your

maximum levy rate is $3.60 per $1,000 assessed value, minus the actual regular levy rate(s) imposed

that year by those districts that the city is annexed to.

13

Fire districts and regional fire authorities have a

maximum regular levy rate of $1.50,

14

while library districts have a maximum regular levy rate of $0.50.

15

Depending on which districts your city is annexed to and what their levy capacity is, your city’s levy rate

may be reduced as low as $1.60.

Note: Your city levy rate is not impacted by any library/fire excess levies, voted general obligation bond

levies, or fire district EMS levies.

• If your city has a pre-LEOFF firefighters’ pension fund: You may impose an additional levy of up to $0.225

on top of the rates listed above (RCW 41.16.060). The use of these funds has been extended to include

LEOFF 1 medical benefits, and the city’s fire pension levy authority will expire when there are no longer any

pre-LEOFF or LEOFF 1 retiree medical obligations remaining.

See the table on the next page for a summary.

11 Technically speaking, most local government levies (except for voted excess levies) are considered to be “regular” levies.

This includes some other levies that may be imposed by cities, such as EMS levies. See the definition in RCW 84.04.140.

12 The firefighters’ pension fund levy under RCW 84.52.763 and RCW 41.16.060 is available to all cities and towns that had

a regularly organized, full-time, paid fire department employing firefighters entitled to benefits under a pension system in

existence before March 1, 1970 – the date that the statewide Law Enforcement Ocers’ and Fire Fighters’ Retirement System

(LEOFF) took eect.

13 See RCW 84.52.769/RCW 52.04.081 for fire protection districts, RCW 84.52.044 for regional fire authorities, and RCW

27.12.390 for library districts.

14 The maximum fire protection district levies are provided in RCW 52.16.130, RCW 52.16.140, and RCW 52.16.160. The

maximum regional fire authority levies are provided in RCW 52.26.140. However, the maximum levy rates will be reduced to

$1.00 if the fire district/RFA imposes fire benefit charges (see RCW 52.18.065 and RCW 52.26.240).

15 The maximum library district levies are provided in RCW 27.12.050, RCW 27.12.150, and RCW 27.12.420.

Table of Contents

20

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

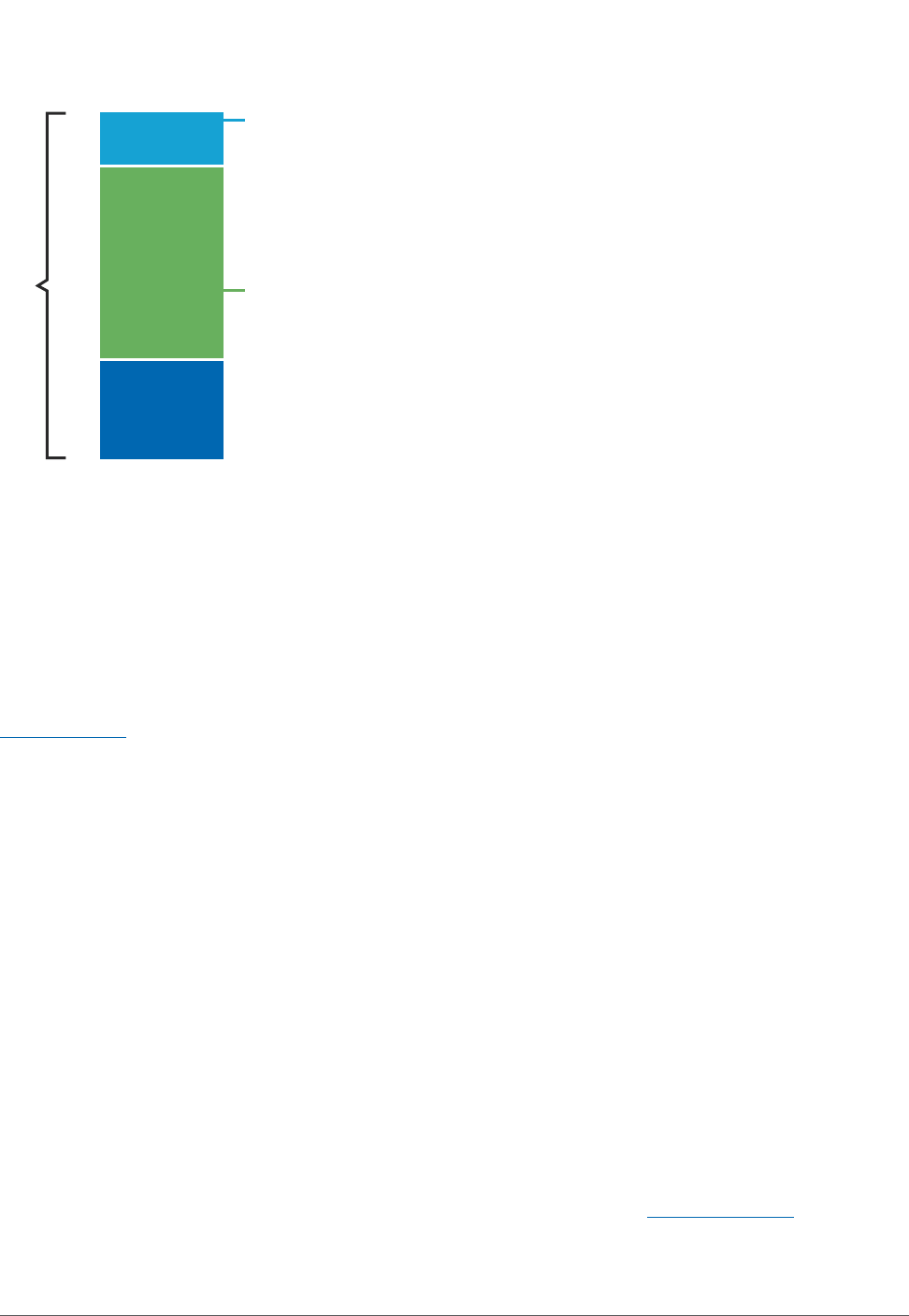

Summary of Maximum Regular (General Fund) Levy Rates for Cities

City is: Maximum levy rate per $1,000 AV

Annexed to library

district?

Annexed to fire

district/RFA?

Without fire pension

fund

With fire pension fund

No No $. $.

Ye s No

$.*

($3.60 minus $0.50

library levy)

$.*

($3.60 plus 0.225 fire

pension levy minus

$0.50 library levy)

No Ye s

$.*

($3.60 minus $1.50 fire

levy)

$.*

($3.60 plus $0.225 fire

pension levy minus

$1.50 fire levy)

Ye s Ye s

$.*

($3.60 minus $1.50 fire

levy minus $0.50 library

levy)

$.*

($3.60 plus $0.225 fire

pension levy minus

$1.50 fire levy minus

$0.50 library levy)

* Maximum “safe” levy rate, assuming fire/library districts levy their maximum rates.

Note that this table shows the maximum “safe” levy rates, assuming that the fire district, library district, and/or

regional fire authority levies its maximum possible rate. For instance, if your city does not have a firefighters’

pension levy and is annexed to a fire district that only levies $1.00, your maximum statutory levy rate will

increase to $2.60 per $1,000 AV ($3.60 minus $1.00). Likewise, if your city has a firefighter’s pension fund and

is annexed to a library district that only levies $0.30, your maximum statutory levy rate will increase to $3.525

per $1,000 AV ($3.60 minus $0.30 plus $0.225).

While this might provide your city with extra revenue potential, you should proceed cautiously. If your city levy

rate is higher than the “safe” levy rate, you may be forced to reduce your levy in the future if the fire/library

district or RFA increases its levy rate. This can cause significant fiscal distress if the city had not strategically

anticipated the possibility.

Use of Revenues

General fund levy revenues are generally unrestricted and may be used for any lawful governmental purpose,

with two possible exceptions:

• Levy lid lifts. If voters approved a levy lid lift (see Levy Lid Lifts) for the general fund where the revenues

were authorized for a specific purpose, the extra revenue resulting from the levy lid lift must be used for

the purpose(s) stated in the ballot measure.

• City fire pension levy. While this is considered part of the general fund levy, the extra levy rate up to

$0.225 is restricted for the firefighters’ pension fund unless the city has a qualified actuary make a

determination that all or part of the additional levy is unnecessary to meet the requirements of the

pension fund, in which case the levy may be omitted, reduced, or used for any other municipal purpose.

Table of Contents

21

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

If the city no longer has any pre-LEOFF firefighter beneficiaries receiving benefits, the levy may be used

for LEOFF 1 medical benefits (RCW 41.26.150(1)), and any amount remaining after the LEOFF 1 medical

benefits may be spent for any other municipal purpose. The city’s fire pension levy authority will expire

when there are no longer any LEOFF 1 retiree medical obligations remaining.

1% Annual Levy Limit

The general fund levy is subject to the 1% annual “levy lid” (see The 1% Annual Levy Lid Limit (“101% Limit”)). If

your city’s assessed value is increasing more than 1% per year, excluding new construction and state-assessed

utilities, your levy rate will begin to decrease as a result. However, if you are levying less than your statutory

maximum rate, your city can potentially increase its regular levy above the 1% annual levy lid using non-voted

banked capacity (if available – see Banked Capacity) or a voted levy lid lift (see Levy Lid Lifts).

Prorationing

The general fund levy is subject to both the $5.90 local limit and $10 constitutional limit (see Maximum

Aggregate Levy Rates). However, it is among the very last levies that would be ever subject to prorationing. In

the event that either the $5.90 or $10 constitutional limits are exceeded, there should be no impact on the city

general fund levy.

However, the firefighters’ pension levy (for those few cities that levy it) does not have the same protection. If

the city is annexed to a library district or fire protection district, RCW 41.16.060 states that the city may not levy

the firefighters’ pension tax if it causes the combined levies of all taxing districts to exceed the $5.90 or $10

limits. This provision does not apply to cities that are not annexed to a library district or fire protection district.

16

If the city is annexed and either the $5.90 or $10 limits are exceeded, the fire pension levy must be reduced,

eliminated, or “bought down” before any prorationing can be calculated by the county assessor.

16 To understand why, consider that the general fund statutory maximum levy rate for a city that has a firefighters’

pension fund and is not annexed is $3.60 per $1,000 AV ($3.375 plus $0.225). If the city is annexed, on the other hand,

the maximum combined levy rate for the city, fire district, and library district combined increases to $3.825 per $1,000 AV

($3.60 plus $0.225).

Table of Contents

22

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

AFFORDABLE HOUSING LEVY

Quick Summary

• Property tax – additional levy up to $0.50 per $1,000 assessed valuation.

• Revenues restricted to finance aordable housing for “low-income” and “very low-income” households.

• Requires simple majority voter approval.

• Subject to $10 constitutional limit but not $5.90 limit.

RCW: 84.52.105

Any city or town may impose a property tax levy up to $0.50 per $1,000 of assessed valuation to finance

aordable housing for “very low-income” households and aordable homeownership for “low-income”

households (RCW 84.52.105). The levy may be imposed each year up to 10 consecutive years and requires

voter approval.

Counties also have similar authority under the same statute, but the combined city/county levy rate may not

exceed $0.50 per $1,000 AV.

Use of Revenues

Originally, the revenues could only be used to finance aordable housing for very low-income households. The

statute defines “very low-income household” as:

[A] single person, family, or unrelated persons living together whose income is at or below fifty percent of

the median income, as determined by the United States department of housing and urban development,

with adjustments for household size, for the county where the taxing district is located.

Eective October 1, 2020 the state legislature also authorized the revenues to be used for aordable

homeownership, owner-occupied home repair, and foreclosure prevention programs for “low-income

households.” The definition of “low-income household” is identical except that households are eligible if their

income is at or below 80% of the county median income.

Before imposing the levy, the city must declare the existence of an emergency with respect to the availability

of aordable housing for low-income or very low-income households within its jurisdiction and adopt an

aordable housing finance plan for the expenditure of the levy funds to be raised. The adopted plan must

be consistent with either the locally adopted or state-adopted comprehensive housing aordability strategy,

required under the National Aordable Housing Act (42 U.S.C. Sec. 12701)).

Ballot Measure Requirements

An aordable housing levy must be approved by a simple majority vote, and there are no validation/minimum

voter turnout requirements. The statute does not specifically address when this levy may be presented to the voters,

which leads us to conclude that the ballot measure can be presented at any special, primary, or general election.

According to MRSC’s Local Ballot Measure Database, Bellingham and Vancouver are the only two cities that

have presented this levy to the voters in recent years, and both were successful (although other cities have

used levy lid lifts, sales taxes, or other revenue sources for aordable housing purposes).

Table of Contents

23

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

1% Annual Levy Lid Limit

The aordable housing levy is subject to the 1% annual “levy lid” (see The 1% Annual Levy Lid Limit (“101%

Limit”)). If your city’s assessed value is increasing more than 1% per year, excluding new construction and “add-

ons,” your levy rate will begin to decrease as a result. However, since aordable housing levies are temporary

and will expire after no more than 10 years, the 1% levy lid is probably not a big concern. Any adjustments to

produce more revenue can be made in the reauthorization ballot measure.

Prorationing

The aordable housing levy is not subject to the $5.90 local limit, but it is subject to the $10 constitutional limit

and may be subject to prorationing if the $10 limit is exceeded (see Maximum Aggregate Levy Rates). However,

this levy is fairly high on the prorationing “ladder” and there are a number of other local government levies that

would be reduced or eliminated prior to the aordable housing levy.

In the event that both a county, and a city or town within the county, pass aordable housing levies, the

combined rates of these levies may not exceed $0.50 per $1,000 of assessed valuation in any area within the

county. If the combined rates exceed $0.50, the levy of the last jurisdiction to receive voter approval must be

reduced or eliminated so that the combined rate does not exceed $0.50.

Table of Contents

24

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

CULTURAL ACCESS PROGRAM CAP LEVY

Quick Summary

• Property tax – additional levy with maximum rate based on retail sales.

• Revenues are restricted and may only be used for specified cultural purposes.

• Subject to $5.90 limitation and $10 constitutional limit.

• Requires voter approval.

RCW: 84.52.821; chapter 36.160

Any city may impose an additional property tax levy for up to seven consecutive years to benefit or expand

access to nonprofit cultural organizations (RCW 84.52.821; chapter 36.160 RCW). The measure requires

voter approval.

Every county except King County

17

has similar authority under the same statute. While the statutory language is

not entirely clear, it is our interpretation that a city and a county may not impose this levy concurrently. In other

words, if the county has enacted this levy and created a cultural access program, no city within that county may

impose this levy as long as the county’s levy is in place. But if the county has not imposed such a levy, or if the

county’s levy expires and is not renewed, the city may submit this measure to voters.

While most of the provisions within chapter 36.160 RCW refer specifically to counties, not cities, RCW 36.160.030

states that if a city creates a cultural access program, “all references in this chapter to a county must include a

city that has exercised its authority under this subsection, unless the context clearly requires otherwise.”

Use of Revenues

The revenues must be used in accordance with RCW 36.160.110, which is very detailed. Originally King County had

separate funding criteria than the rest of the state, but eective June 11, 2020 all cities and counties statewide are

subject to the same criteria. The funds may be used for a number of purposes related to cultural access programs,

including start-up funding, administrative and program costs, capital expenditures or acquisitions, technology,

and public school programs to increase cultural program access for students who live in the city.

A “cultural organization,” as defined in RCW 36.160.020, must be a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation with its

principal location(s) in Washington State and conducting a majority of its activities within the state. The primary

purpose of the organization must be the advancement and preservation of science or technology, the visual or

performing arts, zoology (national accreditation required), botany, anthropology, heritage, or natural history.

State-related cultural organizations are eligible, but the funding may not be used for local or state government

agencies, radio/TV broadcasters, cable communications systems, internet-based communications services,

newspapers, magazines, or fundraising organizations that redistribute money to multiple cultural organizations.

The city may not use the funding to replace or supplant existing funding (RCW 36.160.050). The city must arm

that any funding it usually and customarily provides to cultural organizations will not be replaced or materially

17 King County may only impose a cultural access program sales tax and may not impose a cultural access program levy.

See RCW 36.160.080(1)(b).

Table of Contents

25

Revenue Guide for Washington Cities and Towns | AUGUST 2024

diminished. If the organization receiving funds is a state-related cultural organization, the funds received may

not replace or materially diminish state funding.

Ballot Measure Requirements

The city must adopt an ordinance to impose the levy and the ballot proposition must set the total levy amount